In the 19th century international justice, which is being celebrated this July 17 (The Statute of the International Criminal Court was adopted in Rome on July 17, 1998), was a utopian dream. But at the end of the 20th century it became a reality, first with the conflicts in former Yugoslavia and genocide in Rwanda, then with the launch in 2002 of the International Criminal Court. But this passage from dream to reality has been a shock, which we are only just starting to evaluate.

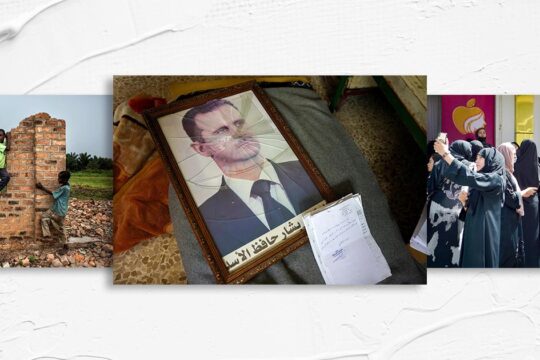

Societies’ thirst for justice cannot be extinguished. In Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and dozens of conflicts around the world, there is a terrible litany of war crimes, echoed by the need of victimized populations for dignity and recognition. But can the criminal tribunals meet these demands? How can the logic of battles of strength and the fairness implied by international justice be reconciled when neither the United States, China nor Russia have ratified the Statutes of the International Criminal Court? How can international justice act when it depends so much on States to build indictments and arrest suspects? How can we not recognize also that some criminal tribunals have been manipulated for political ends, without nevertheless achieving them? Take, for example, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, which continues to exist in a vegetative state, because no member of the UN Security Council dares take responsibility for admitting that it has completely failed.

Clearly, international justice is not isolated from the brutal realities in the rest of the world. In recent years, the increasing power of authoritarian regimes in Russia, Turkey and elsewhere reflects a climate in which human rights are seen as an impediment to the good conduct of affairs. International justice is also suffering from the post-truth politics that we are now witnessing, deepening inequalities within society both in developed and developing countries, and the anger and frustration they generate. President Trump’s unilateralist policies, including drastic cuts to the United Nations and aid to Africa (except for anti-terrorist programmes) complemented by his naive faith in military force, give dictatorial governments an additional alibi to undermine human rights, including international justice which is a human rights pillar. Let us remember what Pascal observed in the 17th century: “justice without force is powerless, force without justice is tyrannical”. But should we therefore lose hope?

Strangely, no, we should not. The obstacles are innumerable, but the last 25 years have allowed us to become aware of certain facts. Firstly, international justice is a reality. Certainly it is a reality which is often denied, badly managed or even in some cases manipulated. But this thirst for justice within societies remains, even if in places like the Central African Republic, for example, the new Special Criminal Court needs to prove its efficiency in a context where most of the country remains in the hands of armed groups. The same challenge exists in a very different way in Colombia and Uganda, as in many other conflict zones: how can justice and peace best be reconciled? Debate about the extent to which amnesties are acceptable remains more open than ever. International justice is not a judicial bureaucracy ensconced in a Western capital. It remains a perspective for the future. The time of dreams is over, it is now time to meet the challenges!

This article is co-published with our partner The Conversation