A group of African personalities, including former key players in international criminal justice, have called on Burundi and South Africa to reconsider their decisions to pull out of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Meeting in Arusha, the Tanzanian tourist town that is the seat of the African Court of Human and People’s Rights and former seat of the now-closed International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), members of the Africa Group for Justice and Accountability (AGJA) published at the start of an October 18 symposium their Kilimanjaro Principles of International Justice and Accountability. The AGJA was founded a year ago in The Hague, during last year’s ICC Assembly of States Parties (ICC member States’ annual meeting). It has 12 members, including former ICTR Prosecutors Richard Goldstone and Hassan Bubacar Jallow, and former ICTR President and ex-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navanethem Pillay.

Under these “Kilimanjaro Principles”, which emerged from a joint forum with Wayamo Foundation, a German NGO promoting rule of law and international criminal justice, the AGJA committed to “encourage a positive and cooperative relationship between African states and the International Criminal Court, as well as advocate universal ratification of the Rome Statute”. The Group members say they will “support international cooperation and offer independent expert advice, facilitation and mediation to African states, the African Union, the International Criminal Court, and the international community”, so as to “foster open, transparent dialogue on the role and impact of international justice in Africa, provide open forums where African states, citizens and organisations can discuss African and global perspectives on justice and accountability”.

Bujumbura “depriving victims of recourse to justice”

As they signed the Kilimanjaro Principles, members of the AGJA knew that Burundi, a small African country that has been in deep crisis for more than a year, had started a process to pull out of the ICC. What they did not know when they signed the text was that Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza had already the same day promulgated a law enshrining the withdrawal. So the next day, the Group issued a declaration urging Bujumbura to reconsider its decision. The AGJA members said the Burundian government’s decision was an “obstacle to achieving accountability for crimes committed in Burundi” and “deprives the victims of human rights violations in the country a recourse to justice”.

ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda opened a preliminary examination in April this year into crimes committed in Burundi since April 2015. At the end of September, the UN Human Rights Council launched an international commission of inquiry on Burundi, after experts published a report saying crimes in that country could constitute crimes against humanity.

The Burundian government, which has become more and more isolated since President Nkurunziza won himself a controversial third mandate last year, has taken up for its own cause the cry of other African countries that international criminal justice is a tool of Western neo-colonialism. Bujumbura must now notify the UN of its decision in order to start the official ICC withdrawal process.

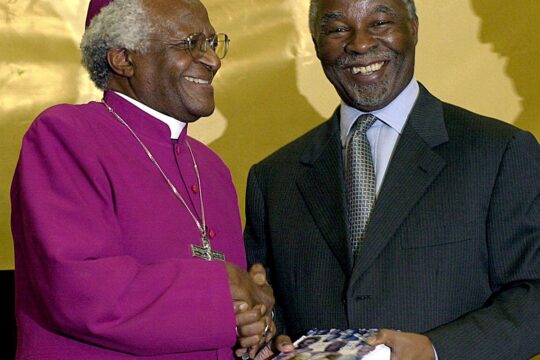

But it was on Friday October 21 that the ICC suffered the worst setback in its tumultuous relations with African States. In a letter to the UN Secretary General South Africa, the continent’s power-house, announced it was pulling out of the ICC. In a new statement, the AGJA expressed “deep concern”. “South Africa is an indispensable ally of international justice and the ICC,” said the AGJA, reminding people that the country of the late Nelson Mandela “played a leading role in the creation of the Court and has been a key supporter of the institution since the ICC became a functioning reality in 2002”. “The South African government’s tradition of supporting human rights and as a leading voice on accountability would be undermined by a withdrawal from the ICC,” it continued.

The AGJA called on South Africa’s parliament to reject the government’s move.

Counterweight in West Africa

Unlike in Burundi, no leader in South Africa is being targeted by the ICC. But over the last five years Pretoria, ever keener to play the voice of Africa, has moved to the side of the ICC’s opponents. Despite action by its strong civil society, South Africa refused in 2015 to execute ICC arrest warrants against Sudanese president Omar Al Bashir who was visiting for an African Union summit. Bashir is under two ICC arrest warrants for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Darfur, in the west of his country. Speaking at a press conference in Pretoria on October 21, South African Justice Minister Michael Masutha said that the application of the Rome Statute (founding treaty of the ICC) was “in conflict with the law on diplomatic immunity”.

Fears of a mass African withdrawal from the ICC seemed to have calmed down after the last African Union (AU) summit in Kigali in early July. But Pretoria’s decision could have a knock-on effect. “South Africa is a big power on the continent, a sort of driving force,” said an AGJA member who did not wish to be named. “There is the fear that it could pull in its wake other African countries among the thirty or so who have signed ratified the Rome Statute. There is certainly a counterweight in West Africa, made up of Nigeria and other countries in the region like Senegal. The campaign in favour of the ICC needs now to bring this support to its aid.”