JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Uğur Üngör

Professor at the NIOD Institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies in Amsterdam.

Almost a decade after the revolution and the beginning of the civil war in Syria, several countries in Europe have started to try Syrian individuals. Former rebel commanders, Islamist fighters, ISIS members or Syrian intelligence officers, they are accused of terrorism, war crimes, genocide or crimes against humanity. Uğur Üngör is a professor at the NIOD Institute in Amsterdam who researches mass violence in the Middle East and has interviewed hundreds of Syrian refugees. For Justice Info, he looks at the limits of these trials and the risks of building Syrian history on it.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: How would you place Syria in the contemporary history of mass violence?

UĞUR ÜNGÖR: Since World War II, there have been a number of civil wars around the world, in Colombia, in Algeria, in Tajikistan, for example. The Syrian war is not unique in terms of the number of victims or duration of the conflict. The conflict between the FARC rebels and the Colombian State lasted decades. I wouldn't even say the Syrian conflict is unique in its brutality – the Chechen context was also particularly brutal. But the Syrian situation is specific in several ways. As a political conflict and a civil war, we are looking at a pacific uprising met with violent repression, which escalated to a multi-sided war. There was never one group against the State, never one frontline but several, controlled by multiple protagonists. There was a fragmentation of the Syrian territory and so, different conflicts. You had the Kurds fighting ISIS in Kobane, and at the same time rebels fighting Assad in Idlib. It is pretty unique.

The international implications are another interesting aspect. We ended up really early in a proxy war, with heavy international involvement, with parties more and more depending on international supports. Some civil wars go by for years almost unnoticed. The civil war in Angola or in Mozambique for example. In Syria, already by late 2012 there was heavy involvement by Turkish, Jordanian, Iranian and Gulf countries. Then the Russians came in, then an “international coalition”. On a single day there could be four different air forces in Syria's airspace...

The surrender of the international community, combined with such impunity, I think is fairly unique”

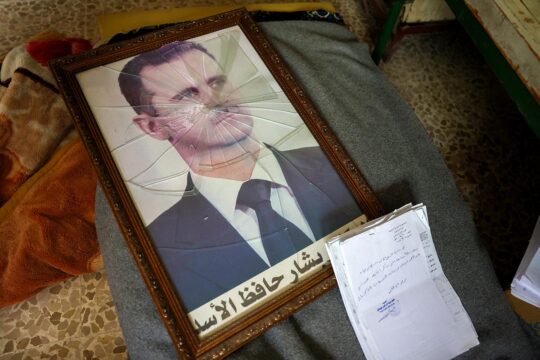

International involvement in a civil war is not a new thing...

No, but where Syria might be unique in my opinion is on the capacity of the regime to hold onto power despite the general knowledge of its mass crimes. After a while, in many civil wars the international community got involved, the United Nations or the regional powers decided to get rid of the leaders. That is what was done with Slobodan Milosevic, who ended up at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia [ICTY]. In the case of the Syrian regime, we have seen indisputable evidence of its crimes. Despite that, [president] Bashar al-Assad remains in power. And some countries which called for the end of his power in 2011 are now considering reopening their embassies. All of this shows not only the power of the Russian support but also the cynicism of the international community. We gave up the idea of doing something about Assad. Some of the top perpetrators who are actually wanted internationally – [al-Assad security adviser] Ali Mamlouk, [head of Syria's notorious Air Force Intelligence Directorate] Jamil Hassan - are still able to travel... Overall, the surrender of the international community over what is perceived as a fatality, combined with such impunity, I think is fairly unique.

Here we are, decades later, still working with Stalin's definition of genocide”

What’s so specific, in the mass crimes perpetrated in Syria?

The “creativity” of ISIS executions, and the way they promoted their own crimes, is quite new, as well as their multi-genocidal campaign. But as striking as these crimes are, it is it is not on the scale of the vast extermination campaign led by the regime. In my opinion, there is a case to make about a genocide in Syria. I do not accept the legal definition of genocide. It is flawed and was voluntarily limited in the Genocide Convention of 1948. When this concept was developed in the early 1930s, it was about a state or a group exterminating another group of people. It could be a religious group, an ethnic group, a social group, a political group, any group defined by the perpetrators and reported as a threat, an enemy. But in the final draft of the 1948 Convention, all mentions of social and political groups were gone, at the requirement of Joseph Stalin and the USSR... and here we are, decades later, still working with Stalin's definition of genocide, although it doesn't fit to the reality of many mass crimes such as the 1965 killings in Indonesia – where the military executed hundreds of thousands of alleged communists. A specific group was targeted, but since it's a political one, it's not genocide.

Why would you consider the Syrian case genocidal?

In Syria, there was a framework of accepted politics, a small box in which you could discuss selected issues. If you stayed out of the taboos, you could work on some things. But if you stepped out of that box, you made yourself vulnerable to state violence. What happened in 2011 is that hundreds of thousands of people stepped out of that box. That act gave them political identity. They became a political category in the eyes of the regime. A category they needed to exterminate, through the repression of demonstrations, killings, arrests, torture, enforced disappearances and then bombings... if we get rid of Stalin's definition, that makes the Syrian case genocidal in my opinion.

The State doesn’t deny its criminal involvement. It’s something very specific to the Syrian regime”

What role has the Syrian state apparatus played?

We have to distinguish the military warfare from the organized and internal violence it perpetrated against its own population, and from the targeted bombings of the civilian population under opposition rule. The system of arrests, torture and enforced disappearances reminds me of the Latin American dictatorships with one strong difference. In Argentina, someone kidnapped by special forces would simply disappear. And the State would always deny it had anything to do with it. In Syria however, the State doesn't deny that someone is in custody, even if it sends the family from one detention centre to another, losing them in the system. The regime even issued death certificates for its detainees, saying nothing of the cause of death but “heart attack”. It doesn't deny its involvement. I don't know the reasons, but it's something very specific to the Syrian regime.

What is also very specific to the Syrian situation is how the medical system was either manipulated or targeted by the regime. On the side of the regime, the medical system has been used, militarized, turned into a tool of violence. And on the other side, the medical staff and infrastructure in the opposition territories has been clearly targeted by the regime. Bombing hospitals, ambulances struck from the air, even an MSF hospital... this is actually unique in history. Even in the Yugoslav wars, ambulances were coming out of the siege areas. Not in Syria.

The first trials are being organized in Europe, through universal jurisdiction. What perception do these trials give of the Syrian crimes?

In general, there is a massive distortion between the individuals judged and the reality of the crimes actually committed in Syria, their nature and their perpetrators. In a nutshell, there are not enough cases against the regime, regarding the extent of its crimes, and a disproportionate number of cases against rebels, rebel commanders, etc. And a few trials of ISIS members. This disproportion is actually a problem in the perception it gives of this war.

What are the dangers of that distortion?

Trials have been important to preserve the memory of conflicts and international crimes. It was very important at the ICTY, for example. But one of the criticisms was that this Tribunal had too many mandates: to judge people, provide a narrative of the war, preserve memory and archives, etc. I think we have to be careful with giving too much historical relevance to the court cases. Preserving historical memory is not their mandate even if they, de facto, participate in it. Last week in the Al-Khatib trial in Koblenz, a confidential witness described the whole system of mass graves he collaborated with. Such testimony is crucial for history. It's incredible material. But because the prosecution against rebels is so disproportionate compared to the prosecution against the regime, we have to be careful about building Syrian history on these trials. There is a distorted perception of the crimes perpetrated. The extent of the crimes judged in the Al-Khatib trial is not the same as in the Abu Khuder trial in the Netherlands, nor in several of the ISIS cases. They cannot be compared.

How do you explain this situation? Because of diplomatic reasons or of the limits of universal jurisdiction?

For both reasons. It is easier to find rebel commanders or low-level opposition fighters in European countries than high ranking regime officials. And the prosecutors would not say "we're not touching any rebel commander until we find more of Assad's torturers". It would not make sense. The very high-ranking regime officials, the main perpetrators, they don't travel to Europe and take the risk of being arrested. Except for Ali Mamlouk, who apparently went to Italy. But it doesn't mean there are not diplomatic issues, as well, surrounding these proceedings, or lack of proceedings. If a country puts many people from the regime on trial, how will it normalize diplomatic relations with the regime in the end? There must be an internal struggle between the diplomatic wing, the intelligence wing of the governments and the public prosecutors. These have conflicts of interest. We know the German prosecutors are extremely serious about prosecuting the Syrian criminals. However, we also know that some of the mukhabarats [Syrian intelligence services] have information about jihadists the German intelligence might be interested in. I suspect they meet, in neighbouring countries. The relations between European countries and the Assad regime won't be permanently terminated.

Linking terrorism and war crimes participates in a confusion”

The Netherlands and other European countries, with the European Genocide Network, developed a strategy of cumulative charges in the cases of rebel and Islamist commanders. Usually accused of terrorism, they are now also accused of war crimes. What is your opinion?

I have an issue with the crime of terrorism and its perception. I don't like the term and what it symbolizes, what it creates in the mind of society. Of course, forms of violence have to be categorized. But in essence terrorism is violence from non-state actors used against civilians. The problem with the 9/11 era is that the crimes categorized under the term of terrorism get a special status, legally and politically. The terrorism jurisdictions and jurisprudence have developed, and the term “terrorism” awakens important traumas in Europe. Terrorism sounds as terrible as crimes against humanity. Although I do understand the reasons behind the prosecutors’ strategy of cumulative charges, linking terrorism and war crimes participates in a confusion which can lead to consider the Al-Khatib crimes and the killings of a low-level rebel commander to be on the same scale.

In Europe, besides criminal cases do you see other transitional justice tools to explore?

There are several things we need to look into, to preserve the memory of this conflict and undermine impunity, at least on a symbolic level. To create, to promote a bank of documents, public archives of the conflict in Syria for historical records would be one thing. It is important to develop an "inclusive" history of this conflict. It's a highly polarized conflict, and different narratives, depending on who tells them, will be taught to the young generations. The Kurdish perspective is one narrative, the regime's perspective is another one, etc. To create a multi-sided narrative was the aim of the Syrian History Oral Project when I started to develop it with Syrian researchers in 2013. The idea was to record the human experiences of this war, to go deeper than the few minutes media accounts of it and create a broad source base with different perspectives. We have interviewed over 500 Syrian people so far, pro-Assad, anti-Assad, civilians, activists, fighters, soldiers -- one of the inspirations being the USC Shoah Foundation, the Institute for Visual History and Education, dedicated to making audio-visual interviews with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust. I wanted to develop the same on the Syrian conflict.

Syrian civil war is now part of the European memory”

What else could be developed?

There are material and immaterial tools of transitional justice. One would be a museum or a memorial. So far it doesn't exist. In Germany where so many Syrians found asylum, it would make sense. To build this in Europe feels important, because of the number of Syrians who are and will be European citizens in the upcoming years. This memory is now part of the European memory. Right now, there are more survivors of Assad's detention centres in the Netherlands than survivors of the Nazis’ concentration camps. Over the past years, thousands of Syrian babies were born in Europe, where they will grow up. You need to have an answer for these children, in a way that doesn't bring hatred. Building museums, memorials is not only a tool of transitional justice for now, it's an educational tool for the next generations.

Interviewed by Lena Bjurström, for JusticeInfo.net.

UĞUR ÜNGÖR

Uğur Üngör is a Professor at the NIOD Institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies in Amsterdam. For the past years, he has researched mass violence in the Middle East and coordinated the Syrian Oral History Project, for which he interviewed hundreds of Syrian refugees on their experience of dictatorship, war and exile. He is currently working on a book about Bashar Al-Assad’s militias and mass violence in Syria.