"Listening to the stories I felt repugnance at our actions. How is it possible to defend as something valid before humanity the objectifying of persons and turning them into merchandise in order to finance a project that vindicated dignity, when we were actually trampling on it?" started Rodrigo Londoño, the last commander-in-chief of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), once known as Timochenko, in a grave voice.

"We understand the pain we caused them when we violently ripped them from their families and social circle, to intern them in camps in the jungle, keeping them there subdued by means of force, isolated from the environment in which they led their normal lives", seconded Julián Gallo, also a former leader of that guerrilla group under the ‘nom de guerre’ Carlos Antonio Lozada. "We came here to own up to the cruelty that this serious crime implied, because it meant making all the families hostages," added Pastor Álape.

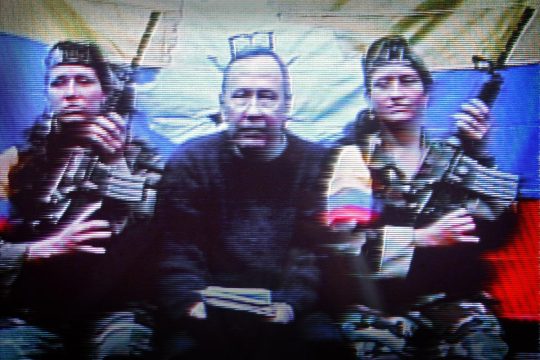

The icy silence in which the victims of their most emblematic crime listened to them contrasted with the brightness filtering through the skylights of the auditorium at the Virgilio Barco Library, a brick building built in Bogotá by renowned architect Rogelio Salmona and recently nominated by Colombia to become a Unesco World Heritage site. In the same mutism, the seven indictees - all members of the 'Secretariat' of the now defunct guerrilla group - listened to thirty direct and indirect victims of kidnapping.

War crimes and crimes against humanity

It was another unprecedented scene in Colombia, soon after military officials acknowledged that they had committed hundreds of extrajudicial executions. Now it was the FARC’s top brass who admitted publicly and in front of their victims that they gave the orders to kidnap at least 21,396 persons throughout the country between 1990 and 2015, and that they failed to control their subordinates, who subjected them to all kinds of humiliation.

At the three-day public hearing, also for the first time, they clearly owned up to the degrading treatment inflicted on their victims and to the ordeal their families endured, finally acting on one of their victims’ most heartfelt demands over the past two years.

Interspersed between the stories of their victims, one by one they acknowledged that, for having drawn up the macabre policy and for the command they chose not to exercise, they were responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity, before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) set up after the Colombian government's peace agreement with the guerrillas.

"We became poets of pain"

Over three days, victims recited the physical and moral effects of kidnappings to those most responsible for their pain, seated a few metres away. On the first day it was the politicians, soldiers and policemen kidnapped in an attempt to secure a swap for imprisoned guerrillas. On the second day, it was those abducted with aim of collecting ransom. And the last day came those who were kidnapped to maintain social control of the territories where FARC operated.

"We became poets of pain due to the absence of sons, brothers and husbands," Gloria Narváez, whose brother Juan Carlos was one of the eleven Valle del Cauca state lawmakers kidnapped in 2002 and murdered five years later, told them.

Could you believe that, in order not to lose my sanity in the midst of forced isolation, I lectured the trees in the jungle, asked Óscar Tulio Lizcano, a congressman who spent eight years in captivity and is now finishing a doctoral thesis on forgiveness. Did you know that, after the kidnapping of Captain Elkin Rivas, my family had to close down their shoe business, his sister Edna questioned. Did other politicians promote the idea of our abduction, asked coffee grower and former congressman Orlando Beltrán.

Why did you, after years of extortion and the kidnapping of my father, set off a bomb against his house which injured a daughter, asked tradesman Héctor Mahecha. Could you fathom that the police had frozen the salary of my father, officer Víctor Hugo, when he was captured, asked Ányela Sierra. Or that he lost his job as a school teacher when he was kidnapped and then saw his house confiscated by a bank, inquired Éibar Meléndez.

"It’s about our tales here"

One by one, FARC’s victims told them about the effects of their captivity, from family breakdowns and lonely childhoods to trauma financial bankruptcies. Among them were politicians, police officers, trade unionists, businessmen and housewives from almost every region of the country. Survivors of kidnapping, wives, parents, children and siblings of those who have not returned, defenders and critics of the peace agreement under which they had convened there face to face.

Wearing a chain around his neck, Major César Lasso regretted that his dream of seeing his three children, including one born after his abduction, grow up was thwarted for 13 years. Her family ties broke down and most of their members don’t speak to each other now after the kidnapping of her father Juan Antonio, Diva Cristina Díaz calculated. Danilo Conta, an Italian who lost his restaurant, told them he is "surviving, waiting to die".

Gonzalo Botero, a cattle rancher from Magangué, told them he was tormented by how hard-earned, honest money - paid for his ransom - ended up in the coffers of a criminal group. Edward Díaz, whose father Oswaldo is still missing, announced he had initiated a lawsuit in the United States, on account of his dual nationality.

Police officer Olmes Johan Duque, a victim of sexual violence during captivity, told them that he is still under psychiatric treatment because he has nightmares and cries. Colonel Raimundo Malagón - who spent two years tied by the neck and feet to two trees - recognized the cathartic potential of the hearing. "It’s about our tales here", he said.

"This damned policy of kidnapping"

After years of publicly justifying kidnapping as a weapon of war, even while negotiating peace, the guerrilla leaders finally accepted the gravity not only of kidnapping, but of the other crimes that accompanied it, such as torture, murder or sexual violence.

"I am guilty, individually, for this damned kidnapping policy, I participated in the conference where it was approved", said current senator Julián Gallo. Rodrigo Londoño spoke of their "human insensitivity" and "savagery", Pastor Alape of the "cloak of darkness" and "humiliation" that they imposed on victims. "We surpassed all levels of inhumanity", Jaime Parra summed up.

Several of their positions were a radical departure from their own initial interventions within 4 years of judicial process before the JEP. They now accepted that there were episodes of sexual violence during abductions, something they’d been reluctant to do in the past. They admitted that they subjected people to forced labour, adopting the special tribunal’s accusations against them - although, following a request from the Inspector General’s Office, the special tribunal later legally elevated this crime to the category of slavery. All of them departed from the term they always used - and which victims abhor - 'retention'. One dubbed it a euphemism.

Perhaps most importantly, they finally referred to the moral damage caused by kidnapping. And their admissions validated the findings by the JEP, which - after four years of investigation - established the largest known universe of victims of this crime, registered 3.029 persons as parties to the case, and detailed patterns that were invisible to most Colombians, such as kidnappings aimed at securing territorial control.

This does not mean that all the specific questions posed by victims got satisfactory answers. Many weren’t because, unlike the hearing on false positives, here were those who gave the orders and not those who carried them out. This is because, as JusticeInfo has told, while the first macro-case against state agents is moving from the bottom up, the first one against the guerrillas started at the top and will then move down towards the regional commanders. It will be them, plus rank-and-file rebels, who will have to answer these questions in a series of hearings in six cities during the second half of this year.

The ten percent who never returned

Although the collective imagination in Colombia about kidnapping has mostly been associated to barbed wire cages in the jungle and prominent abducted politicians, the JEP hearing put its finger on another invisible drama: those who never returned to their families.

"I ask you to put yourselves in my shoes and in the shoes of all of us searching for our relatives. I want you to understand the importance of details, of things that may seem trivial to you, but which for us can be the balm that heals our wounds," implored Daniela Arandia, who was seven years old when her father Gerardo was kidnapped and studied geology to follow in his footsteps. She asked one of the former guerrilla leaders, Milton Toncel, to connect her with anyone who might have known her father in order to, in her words, "continue to create a memory of him, allow me to know him, permit my inner seven-year-old to heal the emptiness of not having a father".

Yoleni Peña resented that they knew that her policeman brother, Luis Fernando, was mentally ill but still decided not to release him. And Augusto Hinojosa, whose brother Ismel and cousin César are still missing, told them his father who died two years ago never smiled again.

There are thousands of families like theirs. At least one in ten of those kidnapped did not return, according to the findings of the JEP: 627 were killed, in cases where their families managed to recover their remains, and 1860 are still missing.

But a few victims found partial answers that day. Carmen Mirke, whose husband Orlando Toledo was kidnapped while working for a contractor of the state oil company Ecopetrol, after telling them about the difficulties of being both mother and father to three teenagers, complained that FARC members told her that Orlando had escaped, when they knew he’d been murdered.

Rodrigo Londoño replied that he was certain that a guard had indeed killed him in 2005 after an escape attempt, that he had heard it on their internal radio. At the justice’s request, he formally stated this so that Carmen can now process his death certificate.

"You’re the only ones holding the truth"

"Give me the opportunity to leave this world knowing where I buried my son. I don't want to know about the moments before his vile murder, but I need you to help us find them," pleaded Vladimiro Bayona, telling them that Alexander and his friend Alberto González - both environmental engineering students - were abducted during a hike in 2000.

"You’re the only ones holding the truth," he said, directing his plea to Pablo Catatumbo Torres, who had command in that area of Colombia’s southwest. "This is often difficult. That military unit had 60 or 70 persons, but almost all of them died during the conflict. I think there are one or two survivors left," the now senator replied. "I will do my best to help you find your son.”

At that point, justice Catalina Díaz interrupted him: "I compel you not to use the word 'help', it is an obligation of all former combatants," she said, reminding him that his legal future depended on his commitment to victims like Bayona.

A seesaw between hubris and contrition

This was not the only moment during the hearing that showed that in restorative scenarios, catharsis and contrition often coexist with arrogance and indolence. While a dozen victims asked to locate the remains of their loved ones, the former guerrilla leaders promised to "do their best", in a language and gestures that suggest a future action rather than a current commitment.

At times the guerrilla leaders argued that they had not been in direct contact with hostages, that communications were difficult, or that - as Rodrigo Granda said - "barbarity was not in our initial calculations". "I never understood the chains, it seemed to me the most degrading thing in the world," said Rodrigo Londoño, failing to add whether he’d done anything about it as the organisation's chief. "They demand too much of us," Granda said at one point.

"Although it was historic to see the top brass of an armed group sitting for the first time in Colombia before its victims, at times they spoke of the 'noise and smoke of war' as if wanting to show that they couldn’t act as commanders and oversee troops’ treatment of hostages. This omits the fact that all world armies, even in war, military leaders exercise command responsibility, even in the worst turmoil," says Gloria María Gallego, a professor at Eafit University who has written two books on kidnappings and who was present at the hearing. She too has experienced four abductions in her family, including one by FARC.

Milton Toncel's change of heart

Perhaps one of the most striking narrative threads was the transformation by Milton Toncel, known in wartime as 'Joaquín Gómez', over the three-day hearing.

"The grey gunpowder cloud didn’t allow us to see anything," he said on the first day, before recounting that they’d even built tents for some hostages like former presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt and that they could sometimes fry meat. "They were free," he even said.

"The reason you’re here is not because of the times you treated them well," Julieta Lemaitre, the justice who spearheaded the case, admonished him. Your acknowledgements, she explained, had to incorporate three dimensions: a legal one, fulfilled by stating the exact charges and your willingness to accept them; a factual one, which involved talking about specific abductions and answering victims' questions; and a restorative one, in which you express your understanding of victims’ suffering, the pain of their families in the absence of their loved ones and the long-term traces of your crimes.

"It was not idyllic," Betancourt, who was not originally slated to speak but asked for a rebuttal, told him. Yes, she explained, Toncel improved her housing conditions once but in the midst of what remained a cruel reality far removed from any norms of war.

Toncel heeded the scolding and gradually showed a more contrite face. "I admit that in all the years of conflict we never stopped to think about the families or the people we kidnapped. Today I look at myself in the foggy mirror of their sadness under the impotence and nostalgia of what is irreparable", he would say at the end of the day, already addressing such degrading practices as charging ransoms for corpses.

The next day, with eloquence and more emotion, he acknowledged aspects of their suffering he had previously ignored. "Kidnapping is such a lethal poison that its effect is moral and it kills, but slowly, both the kidnap victim and his or her family as they live in constant anxiety," he reflected. He promised to work now so that Daniela Arandia can rebuild, in his words, the "affective museum of her father".

He seems to have heard the message sent to him by the 27-year-old geologist. "This is not a step towards staying out of jail. This personal and collective moment that we are living through will allow us all to be free, and I am not only talking about physical bars, but mental ones, which we have felt and carried since the war set upon us", Daniela pleaded him.