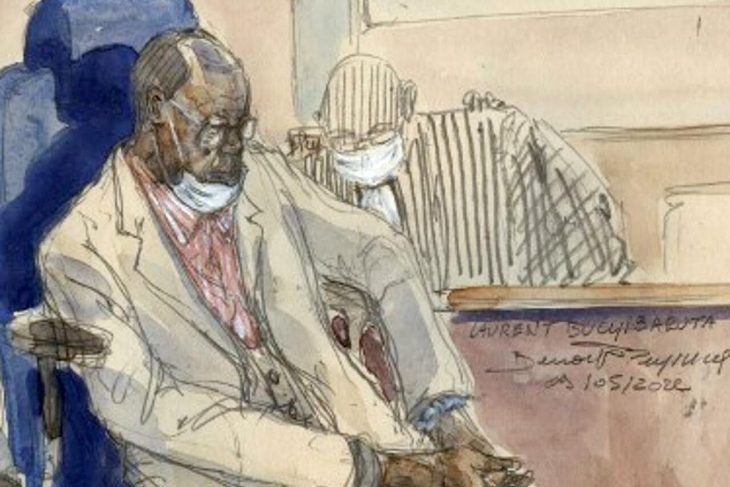

A quarter of a century after his arrival in France, Laurent Bucyibaruta, 78, has had to settle into a new routine. Every morning he enters the Palais de Justice in Paris, walks slowly over the old cobblestones and enters the same courtroom where three other "Rwandan" trials were held before his own. He puts down his walking stick and sits in his chair. With his notes and left arm resting on his lawyers' table, the former prefect stretches out his long legs. It is 9.30 am at the beginning of another day when his frail body and aging face will stay turned patiently towards the nine French men and women - three professional magistrates and six jurors - who have been trying him since May 9 for genocide, complicity in genocide and complicity in crimes against humanity. In his prefecture of Gikongoro, southern Rwanda, he allegedly participated in the massacres of tens of thousands of Tutsis during the first weeks of the genocide in April 1994. He denies these allegations.

In the eighth week of the trial, the fatigue of the Assize Court can be seen on faces and in the irritation of the president, Judge Jean-Marc Lavergne, who is juggling schedule changes for witnesses and is unable to keep the hearing to the length advised by doctors because of Bucyibaruta’s health problems. "I have no choice, I have to free the courtroom on the evening of July 12, we have to continue!" he said one evening after 7pm, when defence lawyer Jean-Marie Biju-Duval protested as he started reading the statements of deceased witnesses -- an academic but necessary exercise in this procedure where the first complaint was filed 22 years ago. Some jurors, engrossed in their smartphones, look up as voices are raised.

The passing of time

Time weighs heavily in this trial and on some of the witnesses testifying on the genocide that has seen the most trials in history. This was the case for 84-year-old Juvénal Rutebeka, who testified by videoconference from Rwanda at the request of the defence on June 28. This former secretary of a commune put a meeting in which Bucyibaruta participated "in 1996 or 1997". "Wouldn't that have been in 1994?" the president asked gently. The witness maintained it was not in 1994 "because the French were there", a reference to the French Operation Turquoise in western Rwanda in... 1994.

“You told the French investigators that ‘he did nothing’. What did you mean?" defence lawyer Biju-Duval asked him.

“I heard about Bucyibaruta in Cyanika, Murambi, Kaduha [places of massacres] but I was not there," Rutebeka replied.

“But you were heard by the investigators in 2013. You said to them ‘as far as I am concerned, he did nothing’. Can we conclude that this information [on his presence at the sites of massacres] was known to you after 2013?” the lawyer continued.

“Yes,” said the witness. “I heard that after 2013.”

“I have no further questions,” said the lawyer.

Can a prefect who stayed alive be innocent?

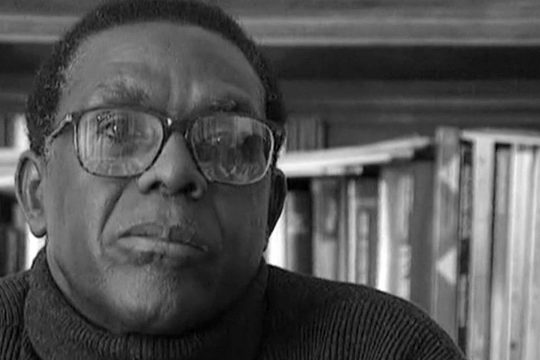

The fundamental question underlying this trial is whether a prefect who remained in office during the genocide and was not a victim of the killers can be innocent. "Those who remained in office agreed with the government's policy, which was the extermination of the Tutsis," François-Xavier Nsanzuwera, former prosecutor in Kigali and former Appeals Counsel at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, told the court in a statement at the start of the trial on May 16. However, he pointed out that "in the specific case of Gikongoro, the gendarmerie commander Christophe Bizimungu did not participate”.

“Is it not true that Bucyibaruta asked for more gendarmes loyal to the President and he said no?” asked Biju-Duval.

"This is the ambiguity of the time," answered Nsanzuwera, who thinks Bucyibaruta acted in a cynical way like others. "You didn't stick your neck out too much, used double talk, appeared respectable and at the same time let it happen."

Major Bizimungu’s name has been mentioned often in this trial. According to a Rwandan refugee in the United States who was heard on June 27, it was he who saved her and her children "at the request of Bucyibaruta", who had known her husband for many years. "I am Tutsi, my husband is Hutu. Bucyibaruta is Hutu, his wife is Tutsi. We were mixed families," Xavera Iyakaremye told the court. "Bucyibaruta decided to act, to send us men of good character," who, according to her account, allowed her to cross a murderous barrier with her children and then remain hidden in Gikongoro until the arrival of the French Turquoise soldiers.

"It wasn’t just me that Bucyibaruta saved. I heard that he was able to save many other people. He is an upright, good, understanding and peaceful man," said the woman, who went into exile in 2005 after her husband, a former magistrate, was imprisoned in Rwanda. At the end of her testimony, Bucyibaruta spoke his agreement. "I presented the case to the commander of the gendarmerie, and it was he who chose the gendarmes to help this family. They had to negotiate rather than use force. These gendarmes were of good will, they accomplished their mission." Presiding judge Lavergne asked if there had been other such delicate missions. "For example, the evacuation of orphans from Kaduha and the nuns from Mubuga in April," the accused replied in a shaky voice.

"The authorities no longer had authority”

The next day, June 28, it was the turn of Pastor Norman Kayumba, who was also heard by video conference from the United States, at the request of the defence. The clergyman’s voice was strong. He was Anglican bishop of the diocese of Kigeme, in the prefecture of Gikongoro, and was in 1994 at the hospital there, where many wounded people were coming and "about 15 Tutsi school students who could not return home”.

Then a group of 250 Tutsi refugees arrived. "The killers were going to attack us, we felt helpless,” said the pastor. “That's when I started to talk to the authorities, the mayor, the commander of the gendarmerie and the prefect”. The witness, dressed in a black suit and red sweater topped with a big cross, leaned back in his chair as if indicating he wanted to share a reflection. "In general, the conclusion I drew was this: the fear I had, the authorities had the same, they were afraid of being killed, that their people would be killed, knowing that there were authorities who were more involved in the genocide than others." He paused. "In Gikongoro, I would say that Bucyibaruta could help me, just as he could perish. What I saw in that country stunned me. In Rwanda, it had become chaos. The authorities no longer had any authority, except for those who agreed to be with the killers."

The witness then returned to his account of the attack that was being prepared. It was late May, "the day of Pentecost 1994”. The killers had surrounded the hospital, and he sent his driver to find Bizimungu, the commander of the gendarmerie. He had known him before the war. "And the prefect arrived in Kigeme because he wanted to have his child treated. I was lucky, I thought, because I had the prefect and the head of the gendarmerie. When the killers’ leaders came, I think they expected us to give them a green light to go and kill. The prefect and I told them that nothing good was going to come of this. I saw that things were serious when they turned on the prefect. It is possible they thought he was hiding Tutsis from them, because his wife was Tutsi. I saw that he had no power over them. It’s possible that he was still making decisions as prefect on other things but not in this attack."

It was then that Bizimungu approached, the witness recounted. He had come with some armed gendarmes, "maybe seven". "He spoke in a serious tone saying 'If you want to confront my gendarmes, stay put. Otherwise leave'. They turned around, saying they were going to come back."

"Being in a position of authority when the country was in chaos was trying. I think Bucyibaruta did what he could," said the Anglican minister. “Whenever I needed him, he was there. The killers did not trust him because his wife was Tutsi and his family-in-law too. As a prefect, he had to be careful. What he could do, he did; what he couldn't do, he didn't."