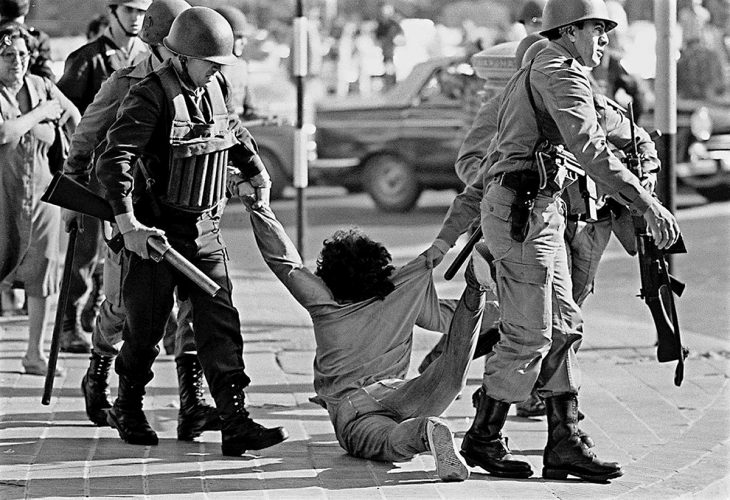

Passing through Campo de Mayo, a 5,000-hectare military base on the outskirts of the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital city, remains, even almost 40 years after the end of the military dictatorship, a frightening activity. There is something there, lost in time, across the old broken wire fences, across the empty security checkpoints, that reminds us of the aesthetics of the Netflix series “Stranger Things”. Only that behind these closed gates, the Demogorgon, a deity or demon associated with the underworld, really existed.

Between 1976 and 1983, more than 6,000 people were illegally detained here. Only 1% managed to survive. They were tortured, endured inhumane conditions of detention before being drugged and, in a dizzy state, thrown alive from planes into the Río de la Plata. They are part of what the world knows as “the disappeared”. Their bodies were never recovered. And worse yet: inside this military base, still today dark and sinister, there was a clandestine maternity where the detainees gave birth to their children – some were kidnapped pregnant while others were raped in captivity. Those babies were then stolen and delivered to appropriators under another identity. Their families are still looking for them. There is a National Genetic Data Bank that conducts studies to identify biological links between people who are suspected of being the children of disappeared persons under State terrorism. Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo is the organization that brings together this search. It is estimated that 500 babies were illegally appropriated. Of these, 130 were able to recover their identity to date.

All this horror came back to light on July 6 when an Argentine court finally sentenced the responsible for these crimes in what is known as the Campo de Mayo mega-case, one of the two largest detention and torture centers of the dictatorship in which more than 30,000 people disappeared. In fact, there were two rulings: the first, issued on July 4, which confirmed the existence of the so-called death flights that left from Campo de Mayo, and the second, issued on July 6, which condemned the torturers.

The lasting pain of stolen children

It required 2,126 court sessions and more than 700 witnesses to convict 19 of the 22 accused of crimes of torture, kidnapping, homicide, as well as raids, aggravated robberies and aggravated sexual abuse against 323 detainees/disappeared. Ten convicts were sentenced to life imprisonment, while nine were sentenced to 4 to 22 years in prison. Another three achieved some form of “biological impunity”: two died before being sentenced and another suffers from a terminal illness, so they escaped judgment.

The verdict of the Campo de Mayo mega-case was read during a public hearing attended by many people inside and outside the courtroom. They had come to accompany the victims and their families who had been through a very long and sinuous search for justice.

It all began with the end of the dictatorship in 1983 and the subsequent Trial of the Juntas, the high command of the Armed Forces. But the incipient democracy did not have the robustness to uphold earlier convictions and after some coup attempts, the guilty were pardoned as early as in the late 80’s. It was not until 2006, 30 years after the beginning of the dictatorship, that the pardons given to the hierarchs of the military regime were annulled, the impunity laws repealed and the trials resumed. Since then, according to the latest survey by the Office of the Prosecutor for Crimes against Humanity, a total of 1,058 people were convicted for these crimes in 273 trials.

Among the victims at Campo de Mayo were 14 pregnant women whose children were appropriated. Five of these children were able to be returned to their families and recover their true identity but 10, today adults, were not. The families of the kidnapped "were also victims of these events, because the conduct of the accused was also directed against them, by deliberately denying them information about the whereabouts of their loved ones," said the plaintiffs’ attorney Carolina Villella during her plea at the trial. "The consequences of this action still persist in the present, generating a burden of pain and anguish for the families, which are sustained over time," Villella added.

Evidence from insiders

One of the great complexities of this case was the small number of survivors. The task of the reconstruction and collection of evidence to expose the modus operandi of the dictatorship was titanic. One of the main sources that informed both judgments were the former conscripts, the young people who performed compulsory military service in those years. They were casual witnesses who managed to bring to light what the high command tried to hide. The testimonies of the gendarmes of the lower echelons were also relevant, especially those who participated in guards outside the detention center and were able to recognize several of those responsible.

In her more than 1,500 page-long closing argument, prosecutor Gabriela Sosti explained that "the facts that are judged must be classified as genocide not only because of the massive nature of the extermination, but also because of the intention to destroy a previously selected sector of the population". Regarding the investigation process, she maintained that “in these trials, there is generally no direct evidence, but different hierarchies (in criminal matters) are identified, from those who were inside the torture center to those who were in other estates".

The legacy

State repression was also directed from Campo de Mayo base, in the northern part of the province of Buenos Aires, where the most powerful industrial complex in the country was located. Among the victims are dozens of workers and union representatives kidnapped en masse in companies such as the Mercedes Benz and Ford automakers, along with many others. Two Ford executives were sentenced to 10 years in prison for being complicit in military repression at the company's facilities. In 2021 the sentence was confirmed and they were the first civilians to be convicted as part of the military repression.

This is one of the challenges still pending for the Argentine justice: to define the role and responsibilities of civil actors within the repressive structure of the dictatorship. Although there are more than 30 open court cases, progress is uneven.

"Whenever a transition process from a period marked by violence and authoritarianism seeks to reach democratic consolidation, the desire for revenge and hostility that lead to the resurgence of violence must be overcome," analyzed the sociologist and researcher Elena Zubieta in her study 'Argentina: the impact of the implementation of Post Dictatorship Transitional Justice measures'.

Although public opinion seems a bit saturated after almost 40 years of news about criminal accountability for the dictatorship’s abuse, the truth is that no one doubts the truth of the crimes anymore and, even more significantly, beyond the deficiencies that Argentine democracy may have, with its cyclical economic crises, the interruption of the constitutional order does not seem an alternative for anyone. The strength of the families of the victims remains intact. They continue their quest for the restoration of identity for appropriated children who grew up in adoptive families. They continue to push for trials, not only with the obsession of punishing the guilty – many are already dead or so old that they cannot even be moved from their homes – but rather seeking to shed light on the past to finally allow mourning, to go through the grief that helps to unlock that feeling of horror one can feel when passing through Campo de Mayo, to close that portal of pain and impunity for the new generations.