The 90-km of newly tarmacked road from the north of Hoima oil city to Buliisa in the west of the country on the east side of Lake Albert has been baptized by the local population the “oil road”.

At daybreak in mid-July, we were greeted by an anxious looking army of baboons. Some carried their young ones on their backs or under their bellies as they foraged. Others carried their loot of corn from small peasant gardens around grass-thatched homesteads, as they crossed from rural hamlets into the Buliisa game reserve in the Albertine region. Baboons mingled freely but kept a safe and respectful distance from local farmers who were going to their gardens far away, many of them dressed in tatters with hoes in their hands. Most people trudged the new tarmac road with bare feet, including school children.

As agreed with our guides, we were to be in Kasinyi village before the all-powerful and most feared village chairman, Gilbert Barikurungi, woke up for his daily work, including checking on foreign visitors, the media and other "undesirable people" who may have visited the community under the cover of darkness or when he let his guard down.

Barikurungi is one of the officially known members of the smallest local government unit whom locals say doubles as informer for the French conglomerate Total Energies and the government of Uganda, both have vowed to ensure that the Tilenga oil project succeeds at any cost, despite local and international concerns about human rights violations, inadequate compensation, environmental destruction, mass displacement of people, intimidation and harassment of the local people.

1 billion barrels of oil

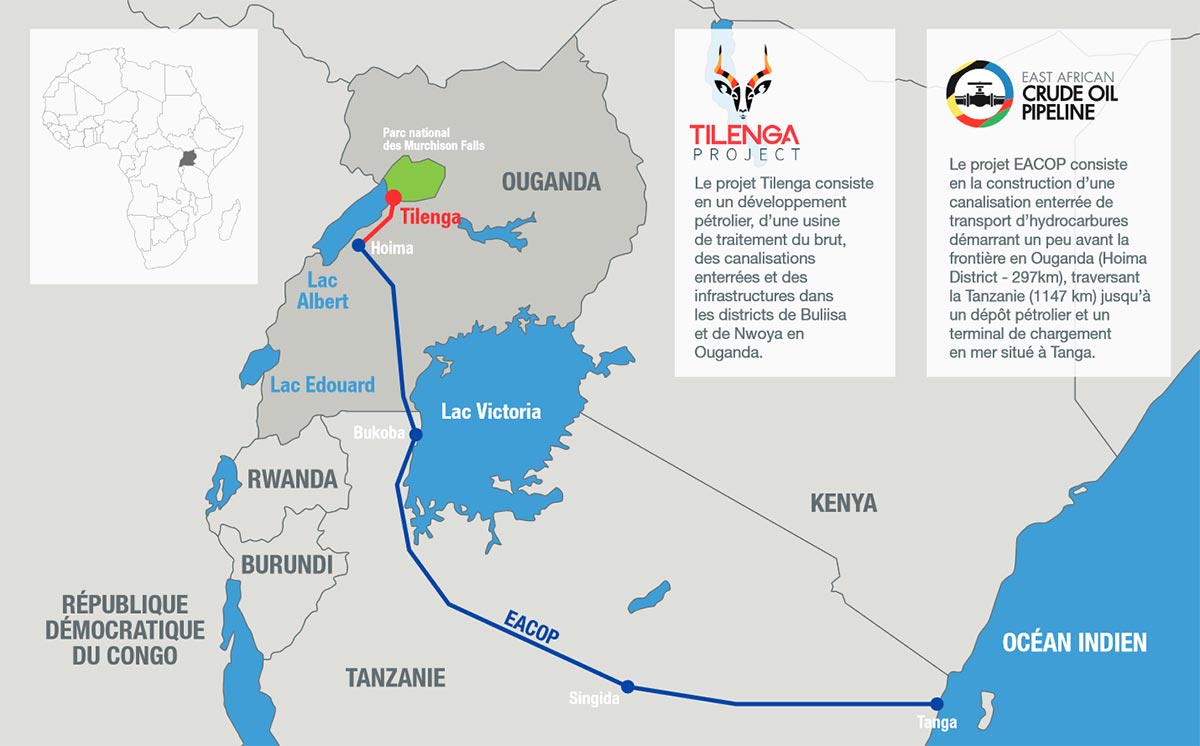

The 9 billion euro Tilenga project, which is planned to start its operations in 2025, is aimed at extracting about 1 billion barrels of oil from under Lake Albert and its shores. In the process, about 100,000 people should be displaced from their homes. In the Buliisa district alone, that will represent a third of its population.

The area has been placed under a blanket lockdown and requires high-level government clearance for media or rights groups interested in the oil story. "You have to be out of this place before the chairman wakes up. If he notices any stranger, he alerts the police and the military, and this is not good for us," one of the guides warned me in a harsh tone. "He is dangerous," he stressed.

“First give me the names of people complaining about me. At least a few names before I can give you comment,” Barikurungi demanded when sought for comment by Justice Info. “Issues to do with oil here are very sensitive. You need to disclose who complained to you and I get their details. Without giving me the names, I can’t give you comment,” he said before hanging up the phone.

On November 9, 2021, a European Union Mission of diplomats was ordered out of the region immediately and given police escort to ensure they exit despite clearance by the Ugandan ministry of foreign affairs, according to a member of the EU delegation in Kampala. That same year, Maxwell Atuhura, a human rights defender whose organization AFIEGO had helped members of the local population go to court to challenge inadequate compensation, and Federica Marsi, a freelance journalist, were arrested by the Resident District Commissioner and the District Police Commander of Buliisa in a hotel where they were staying while interviewing communities affected by the Tilenga project.

“We are looking at oil as a curse not a benefit”

Kasinyi village, where an Oil Central Processing Facility (CPF) has been set up, is about 1,5 kilometres from the homestead of Jealousy Mugisha. Mugisha, 50, is the father of seven. His family is among seven that are still in court for allegedly obstructing a government programme after they protested against inadequate compensation for their land. "My home was documented as a secondary home. At the beginning, we did not understand the difference between secondary and primary home until we went for disclosure, to show us the value of our property taken over by the oil project," Mugisha told Justice Info. "I was told that as the owner of a secondary home I was to take cash compensation, while the primary home owners were to take land for settlement," he explained. "My wife and I said the project found us on the land, that we have lived in our permanent homes for all our life and that we were not taking cash," he said. "Then I was summoned to court in Masindi by the Attorney General. Other members of our family were ordered to accept compensation for the land measuring 13.5 acres, each at 3.5 million Uganda shillings (about USD950) plus a disturbance allowance of 30 percent," he added. "For me I am not demanding a house but a home because I had my house, and I had built another house for the older boys and another for the girls."

On 30 April 2021, Mugisha and a few remaining plaintiffs lost the case. The rebellious residents have appealed, and 15 months later their case has not been heard. "We as a community feel that the government has not helped us but instead oppressed us," Mugisha said. "When we raise our issues, the Resident District Commissioner (area representative of the president), the District Police Commander, internal security and the army come and harass us, saying that we are fighting a government project," he said. "We are looking at oil as a curse not a benefit. They know the little they are giving us in compensation is not enough to buy us another piece of land. We are in a similar situation as Ken Saro-Wiwa was, at least from what we heard and watched on videos, and we shall press on that journey so that our children do not have a bad legacy that we did not have land," he added, referring to the Nigerian writer and leading activist who was executed in 1985 after he had exposed the fate of his Ogoni community in Nigeria’s oil delta region. Mugisha's wife added that they also have to take care of her 78-year-old mother-in-law, a housewife and widow with three other dependents.

Fighting over compensation

Geoffrey Byakagaba, a 43-year-old farmer and father of 10, is one of the few remaining residents who are fighting the case in court. He resides in Kasinyi near the Central Processing Facility. In 2017 Total offered him 2.1 million Uganda shillings per acre (about USD560), but he rejected the offer on grounds it was not adequate. A delegation of 16 cabinet ministers headed by the then minister of Lands Betty Amongi raised the figure from 2.1m to 3.5m per acre as cash compensation, he said. "We’d rather get no kind compensation as there was evidence of purchase of land in the area between 10m and 15m shillings [per acre], " Byakagaba said. Alternative land was found at Nyakatokye, in neighbouring Kigorobya county, and some of the project-affected people liked it. "But the land at Nyakatokye was sold at 7 million per acre yet Total insisted they were giving us only 3.5 million. In the meantime they were giving us a deadline to leave our ancestral land," Byakagaba explained.

In a written response to Justice Info, Gloria Sebikari, spokeswoman for the Petroleum Authority of Uganda, a government body in charge of the oil project, said that “acquisition and/or use of land for petroleum operations duly respects the rights of the landowners and obligations provided for in the country’s laws. Compensation rates for crops, trees and other non-permanent property are determined by the district land board(s) on an annual basis and approved by the Chief Government Valuer in the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. These rates are reviewed to ensure equity and that they are in line with prevailing market prices.” She said that “the decision to increase the land compensation rates was made by Cabinet following a Joint Ministerial consultative meeting that was held with the Project Affected Persons in Buliisa in 2018.” According to her, “the project developer (Total) together with the affected communities and their leaders had identified several pieces of land both in Hoima and Buliisa districts, and Nyakatokye was one of the many options, which the PAPs [Persons Affected by the Project] still declined to take up”.

She also claims that some of those affected by the project opt to move from the rural settings to the urban areas or to places with higher productivity and level of development where they cannot find the same market values. “No PAP whatsoever is forced to take up any compensation values against their will and all the compensation payments are only made after mutual agreement between the project(s) developers and the PAPs following a very vigorous process witnessed by all concerned parties including the PAPs, government officials, project(s) developers, compensation management contractors, and the Chief Government Valuer among others.”

Military presence and government tricks

Notices of vacation to the residents are planted at every point in most parts of the regions where the oil pipelines will pass. Numerous military are detached in dense forest cover, out of sight of visitors. A major military barracks is at Butyaba, along Lake Albert, which borders with the Democratic Republic of Congo. From a distance, we saw several amphibious vehicles, a helicopter gunship and an assortment of artillery weapons. Foot patrols and several military road blocks are located at strategic sites and we once saw soldiers atop a rock with binoculars as our vehicle entered the Biso gorge on the way from Buliisa to Hoima.

Byakagaba said two meetings were held with the Petroleum Authority of Uganda in the administrative capital of Entebbe, about 400 km away. An agreement was reached for land to land transaction for the project-affected people, but this too fell flat. "At first they gave us transport to the Entebbe meeting and later they said money was not there, but this was intended to wear us down. They knew we did not have money to cover that journey whenever called," Byakagaba said. "The last nail in the coffin came with the April 30 [2021] ruling. Only two of us were in court, others having failed to raise the transport fees. Two days after the ruling the construction machines from Total were at the site, meaning all was planned. The Judge said he was giving us 60 days to accept the money for compensation or appeal, but this was when the country was going into Covid-19 lockdown."

No evidence, according to Total

In a written response to Justice Info, Total Energies says that “no evidence has been found that the Company or its contractor ATACAMA with the support of state agents exercised any pressure on PAPs in the voluntary resettlement process, nor communicated in an aggressive or misleading manner to convince PAPs to sign compensation agreements”. The company explains “that in the absence of conclusion of the resettlement process on a voluntary basis, similar to many other countries around the world, local law provides for the implementation of compulsory resettlement under a judicial process” and that “it is possible that some PAPs on being informed of the prospect of such judicial process, were unsettled, or felt pressure”. It stresses “that the vast majority of grievances relate to issues in connection with counting of crops and characterization of crop maturity” and that “many of these grievances have been concluded in favour of the PAPs”.

Total also says it “is not aware of any allegations by human rights and environmental defenders of threats or retaliation made by its subsidiary, contractors or employees in Uganda or Tanzania”. When it was informed about the arrest of Atuhura and Marsi, it claims it “intervened with the Ugandan authorities” and “took the initiative to inform the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN OHCHR), based in Uganda”.

Environmental impact

Since his childhood, Byakagaba has never been engaged in charcoal burning, which destroys their ancestral land. But with orders to stop cultivating and rearing animals on the forcefully acquired land, he said he has been forced to do this to eke a living. "With less to eat and a heavy workload, charcoal burning has brought me back pain. I have had to go for medical treatment at a huge cost," he said.

Residents in the Albertine region are also concerned that flooding due to the construction of industrial parks has destroyed their gardens and caused water pollution. They also want the government to compensate them for 200 metres of land – the distance government demands as a buffer zone from the central processing facility, the oil production wells, the pipeline and the industrial parks – which was not included in the compensation package.

"They want us to sign and give 200 metres of our land to the oil projects as a neighbour, but they don't want to pay for it; yet it is the footprint of the oil project," said Isaac Mugume, a 57-year-old farmer from Hoima District. "Even when we sign documents related to the land acquired by Total, they don't give us copies," he added. (Total itself denies withholding any copy of agreements for the expropriated land.)

PAU’s Sebikari said that “human rights monitoring and mitigation is an integral part of projects’ implementation in the oil and gas sector” but that the PAU “has not received any documented human rights violations and remains open to receiving information and evidence on such”. Sebikari said that the “government is aware of all the vulnerable groups that have been affected by the oil project in Uganda” and that “the ESIA (Environmental Social Impact Assessment), land acquisition processes and respective management plans ensure documentation of the vulnerable groups and their unique needs”.

Complaint against Total in France

On our visit, we saw some of the one-roomed houses of Total Energies’ Resettlement Action Plan abandoned in the jungle as the would-be beneficiaries claim they were too small for large African families, very hot in the tropical sun and dark inside as light could not penetrate the heavy metallic windows and doors fitted, and there was no electricity. An official told us the metal doors and windows were intended to protect occupants from burglars that had infiltrated the area due to the expected oil boom. However, speaking at the launch and handover of houses to the beneficiaries, Pierre Jessua, the then General Manager of Total Energies Uganda said that “this resettlement housing project is an important symbol of our commitment to undertaking the Tilenga development project while observing the utmost human rights standards”. In its written response to Justice Info, the corporation says it has not heard of such criticisms, while also saying that “during the deployment these habitats have been improved, taking into account the inadequacies of the first housing built”.

This situation has earned Total a lawsuit in France for failing to comply with the law on the duty of care for multinationals, passed in 2017. Under this law, companies are responsible for ensuring that the activities of their subsidiaries abroad comply with social, environmental and human rights standards. The complaint was filed by four Ugandan and two French NGOs in October 2019. As Total's appeals were rejected by the French Court of Cassation in December 2021, the case is now to be heard on the merits.