In France, the victim participates as a "civil party" in a criminal trial for the sole purpose of compensation or to support the prosecution. In matters of terrorism, the special Assize Court does not have jurisdiction to rule on the civil parties’ claims for compensation, as this prerogative is reserved for a Victims' Guarantee Fund. Thus, at the trial of the November 13, 2015 attacks, which was held between September 2021 and July 2022, the victims could not claim compensation.

However, they were offered a unique and unprecedented opportunity. Invited to testify extensively, they were able to express their suffering and their quest for the truth about the roots and the course of the attacks. During these ten months of trial, a dialogue was even established between certain defendants and certain victims. As a result, and in many respects highlighted below, this trial seems to have departed from a traditional hearing and applied certain mechanisms characteristic of so-called restorative justice.

The emergence of restorative justice

French procedures are largely inspired by the classic model of retributive justice. This model allows the State to inflict punishment on the perpetrator of an offence in proportion to the seriousness of his or her behaviour, in the name of an established moral and legal order. This model focuses on the guilt of the accused. The victim participates only to give testimony and, in Latin-Germanic traditions, to claim compensation.

Thus, retributive justice responds to violation of the law, whereas so-called restorative justice [in France advocated particularly by the Sauvé Commission, for crimes committed within the Church] is primarily concerned with the violation of the victims’ rights. In an effort to produce beneficial effects in the future, it places the victim at the heart of procedures by focusing on repairing the damage caused by the offence and restoring the social link. This damage includes emotional harm such as loss of dignity, wellbeing, confidence, security and self-esteem. Reparation is understood as a holistic process in which formal acceptance of the victim's story of suffering is paramount, and dialogue between the victim and the perpetrator is possible.

As for the accused, they become proactive in the proceedings that concern them. Their participation aims to make them aware of the consequences of their actions and create empathy towards the victim. This process contributes to humanizing the accused by confronting him or her with the suffering caused, and thereby preventing recidivism. Thus, the central element of restorative justice is the meeting, requested and prepared, between perpetrators and victims, and the promotion of a constructive dialogue between the two main actors of an offence.

Trial on the most deadly attacks in France

In the case of mass crimes, these restorative mechanisms are often applied outside a judicial framework, such as in truth commissions. Trials for mass crimes, such as those conducted by international criminal tribunals and the International Criminal Court, are largely retributive. The only model that has seen a judicial institution applying restorative justice for mass crimes is the Special Jurisdiction for Peace created in Colombia in 2018. This jurisdiction promotes, at each stage of the proceedings, the meeting between victims and perpetrators with the aim of listening to, and recognizing the victims, revealing the truth and formulating an apology.

Victims' rights and restorative justice mechanisms have thus developed over the last few decades. This progress has sometimes been enshrined in law, but in some cases shifts are occurring spontaneously. For example, the trial on the most deadly attacks in France, although governed by an established criminal procedure, seems to have granted new prerogatives to victims.

Unrestricted voice given to victims

In the trial on the November 13, 2015 attacks, the court devoted more than six weeks to hearing 399 civil parties. The victims gave both a common and individual account of the violence inflicted by the attacks. Some of them spoke at length about the suffering they endured and the extent of their losses, even though this was not the purpose of the hearing under the law, as the Court was not ruling on their compensation. Also, their speech was completely free and was never questioned: the Court did not interrupt or question the accounts given before it. The prosecution and defendants' lawyers also refrained from doing so, thus putting aside the adversarial process inherent in traditional criminal trials.

Facing the challenge of hundreds of civil parties participating, the court was keen to allow all those who wished to speak to do so, and arranged with the civil parties' lawyers to that end. A web radio with secure access was set up to offer civil parties who were unable or unwilling to travel the possibility of following the proceedings live. In an unprecedented way, in order to prepare them to the trial, logistical assistance and a psychological support system were set up by the association Paris Aide aux Victimes in the vicinity of the courtroom and by telephone, throughout the trial.

Given this special attention, some victims described the trial as a liberating and salutary space for expression, and as a stage in their reconstruction. A plaintiff who lost her companion at the Bataclan told daily newspaper Libération: "Exhausting the story of that night, meeting other people who lived through it, really was valuable. Through this trial, I was able to gather the broken pieces and rebuild, reanimate the woman I was before. These ten months, at the same time very long and very short, were a spectacular advance. They allowed me to digest my tragedy".

In addition, various sociologists, Islamologists and political figures, including former French President François Hollande, were called as witnesses by victims’ representatives. Despite their ignorance of the criminal case, the Court did not object. This testimony clearly had a purpose other than to provide evidence for the prosecution or defence. As part of the reparative process, these interventions were able to provide the victims with answers about the complex social, political and international phenomena that caused their suffering.

The accused's evolution at the hearing

It is also important to note how the behavior of the accused changed when they came into contact with the victims during these ten months. Confronted with the poignant testimonies of the traumas inflicted and in response to the victims who had expressly asked them for explanations, they opened up to them, and certain words of humanity left their mark. One of the defendants, Sofien Ayari, reversed his choice to remain silent, stating that he was expressing himself "for a precise reason, unrelated to the sentence, the judgment. I did it for the people [the civil parties who testified] who touched me”.

It is also worth noting the evolution during the hearing, after years of silence during the investigation, of Salah Abdeslam, the last living member of the November 13 commando. He finally decided to explain the facts and apologized to the victims. The psychiatrist Daniel Zagury told the court that it was "objective to say that he has evolved towards something less closed, less constrained, which allows us to envisage a way out of his shell”. According to this expert, after six years of extreme isolation, the "social life" made possible by the hearing could have played a role in his transformation.

This transformation was scrutinized by all: the defendants were expected to provide answers to the victims. The judges, the public and the media kept a close eye on their emerging empathy and their contribution to reconstruction for the victims through giving precise elements about the facts. While these expectations were initially implicit, they were later clearly expressed. Thus, on March 15, 2022, when confronted with Abdeslam's statements which she considered insufficient, one of the trial judges told him that "the civil parties are waiting for other answers", thus revealing one of the restorative objectives of the trial: that of providing the victims with the necessary and expected truth. The media also relayed every expression of humanity, every tear, apology and show of remorse, thus putting this restorative process at the centre of the hearing.

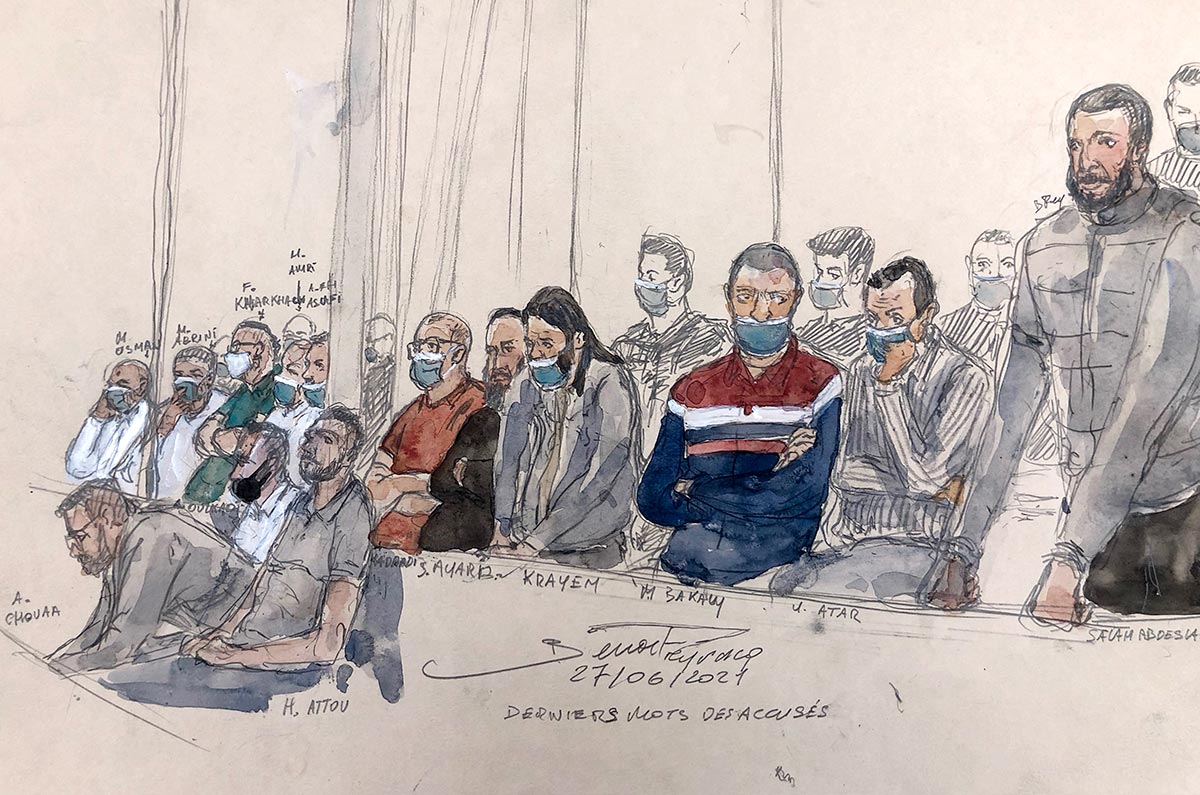

In the case of the November 13, 2015 attacks, no confrontation between the defendants and the civil parties had taken place during the investigation. The meeting therefore took place for the first time, nearly six years after the events, in a courtroom designed specifically for this trial and the trial of the Nice attack, which opened on Monday September 5. One of the lawyers for the accused Farid Kharkhach said in her plea that she regretted that the architect had placed the benches of the defence "face to face with the civil parties and not side by side”.

None of the defendants' lawyers adopted an adversarial defence. Bridges were even built between the two sides of the Bar. During the recesses, it was usual to see the three defendants, under judicial supervision, share a moment with victims or their relatives. A civil party told the press that she wanted to meet the detained defendants in order to "meet their eyes so that each could read the humanity of the other". Finally, ten of the 14 defendants present addressed the victims during their last words to the Court before it retired to deliberate. Kharkhach, for example, acknowledged "the courage, respect, humility (...) and forgiveness" that they had taught him during the trial.

The prosecution’s “retributive” stance

In any case, the legal framework of the hearing did not oblige its actors to follow this restorative process. Moreover, although this trial borrowed certain practices specific to restorative justice, it is not possible to report on a uniform feeling of the victims. The process of personal reconstruction is specific to each victim and an analysis of the most widely reported speeches cannot replace an individualized approach. In fact, of the nearly 2,300 victims who filed as civil parties, only 399 testified in court and only about 60 attended the hearing regularly. The absence of the vast majority of them makes it difficult to conduct an exhaustive empirical analysis of the restorative virtues of the hearing. In addition, the trial does not mark the end of the reconstruction process. The effects of the trial are long term and need to be studied in the long term.

In addition, and in view of these new dimensions, actors in the trial also showed reluctance to fully enshrine a restorative process. Drawing lessons from the trial of the Charlie Hebdo and Hyper Casher attacks, the National Anti-Terrorism Prosecutor's Office asked to be given the floor before the lawyers for the civil parties, contrary to the hearing procedure, in order to avoid having its questions asked by the victims beforehand. Moreover, the particularly bellicose terms used by the public prosecutors marked the retributive posture of the prosecution, borrowing the rhetoric of war and monstrosity ("bloodlust", "demonic ammunition"), and even going so far as to use the semantics of the Islamic State ("Lions" to designate the members of the commando). Some of the lawyers deplored the lack of individualization of the detained defendants in the Public Prosecutor’s indictments and lack of consideration of how they evolved during the hearings.

The specially composed Assize Court did not fully grasp the restorative developments of the trial either. Its ruling communicated to the parties gives place to the victims only to a tiny degree, despite the extent of their participation in the debates. A lawyer for the civil parties thus questioned the impact of these ten months of intense hearings on a judgment that is similar in many respects to the indictment order issued on March 16, 2020. Finally, Salah Abdeslam's sentence of life imprisonment without parole has eliminated any possibility of rehabilitation, ruling out a restorative dimension to his sentence.

Formalizing these developments?

This exceptional trial, conducted by a specially composed Court in a building designed for the occasion and with the active participation of a very large number of victims, is similar in many respects to a transitional justice mechanism. While it has been a retributive trial, it has given a singular place to the victims. Their participation has been even more important than in international tribunals competent to deal with mass crimes, such as the International Criminal Court, where their contributions remain residual.

However, these restorative processes are not framed by the law and raise the question of their scope and limits. As a noteworthy example, although no cross-examination of the civil parties was conducted during the six weeks of their testimony, some defence lawyers challenged the possibility of allowing the victims to testify by video recording, on the grounds that this prevented them from exercising their right to ask questions. While this opposition was described as "sterile" by the president of the Court, it highlights two worlds colliding: the classic formal, adversarial criminal procedure confronted with a practice that aims to be restorative and promoting dialogue.

Analysis of the November 13 attacks trial calls for a reflection on the opportunity to formalize these developments - and to consecrate the restorative virtues that can be found in the trials of perpetrators of crimes causing a very large number of victims. In the context of the trial of these crimes, the integration of mechanisms specific to restorative justice, such as a dedicated space for expression allowing victims to express themselves and be officially recognized in their suffering, could be envisaged. Meetings and exchanges between perpetrators and victims could be proposed, in order to provide victims with answers they want, to encourage the formulation of possible apologies and thus to seek full reparation. In addition, the psychological support offered to victims could be extended to the accused prior to the hearing, in order to better prepare them for this potentially transformative encounter.

Such measures should be rigorously weighed and framed by the law in order to confirm the progress observed during this trial. The dynamics that have emerged naturally could then augur an evolution of criminal procedure towards more restorative justice.

Shoshana Levy is a lawyer specialized in international criminal and humanitarian law. She has worked in the field of transitional justice, including at the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, and for academic research centres. After working for four years in support of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace in Colombia, she is now a judge-assessor at the National Court of Asylum.

Helin Köse is a lawyer at the Paris Bar. She has worked as part of a defence team at the International Criminal Court and for Amnesty International in Istanbul. After working with the law firm Marie Dosé & Judith Lévy, she now practises criminal law. In 2022, she founded the Centre for Analysis, Monitoring and Study of Anti-Terrorist Justice (CAVEAT).

Lucille Vidal is a lawyer at the Paris Bar. Trained in international criminal law in the Netherlands, she joined the Paris law firms Dupond-Moretti & associés and Henri Leclerc & associés, specialized in criminal law. She is currently practising in the international department of Vey & associés. She attended the trial of the November 13, 2015 attacks representing civil parties.