Former congressman José Cardona Hoyos was murdered two days after his book reached bookstores. The title of the publication he’d paid for out of his own pocket and barely managed to distribute among some friends, 'Rupture', was precisely that: a scathing critique of how the Colombian Communist Party in which he’d been active for 38 years had finally yielded to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and embraced their thesis of the "combination of all forms of struggle".

That night of May 8, 1986, Cardona left the Santiago de Cali University where he taught contemporary history. He was walking home when he was approached by two unknown men on a motorcycle who shot him three times. His murder went unpunished, but his family has since been convinced that his executioner was the guerrilla whom he had opposed as a communist leader.

Three decades later, his namesake son, José Cardona Jiménez, has been insisting that former FARC guerrillas - who disarmed following the 2016 peace agreement with the Colombian government - acknowledge their decision to kill the man who had urged them in the late 1970s and early 1980s to do exactly what they are doing today: swap their weapons for the ballot box and seek political power with support of the working and peasant classes, through democratic and non-violent means.

Cardona's murder is illustrative of cases where victims feel that, despite the progress made by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which delivered its final report and completed its mandate mid-year, the FARC has not yet fulfilled its commitment to uncover the truth and own up to all its crimes.

Like Cardona, victims of La Gabarra massacre are calling on former FARC members to redouble their efforts to acknowledge that crime and clarify the circumstances under which they committed it. They value that the former rebels publicly admitted the murder of 34 coca-gathering peasants on a farm in the Catatumbo region in 2004 and that they finally clarified that their relatives were not right-wing paramilitaries, but find their explanation that it was a fortuitous act committed by a commander who disobeyed their orders unsatisfactory. They’re also upset with the TRC’s decision not to release the documentary it made with victims about the massacre as a form of symbolic reparation.

The two cases, besides highlighting the rebel group’s cruelty, contradict their narrative that they were an army that defended the peasantry and left-leaning citizens.

A massacre long downplayed by FARC

Esteban Hernandez narrowly escaped the La Gabarra massacre, one of the worst perpetrated by the former FARC. In the early morning of June 15, 2004, a group of rebels arrived at the La Duquesa farm where he worked collecting coca leaves in Colombia’s northeast, near the Venezuelan border. After jolting the farmers from their beds without explanations, they tied their hands and began to kill them.

Esteban, a lively 53-year-old farmer, took advantage of a distraction from his captor to throw himself into a ravine. Although he was merely wearing boxer shorts and a thick thorn pierced his foot in the jump, he remembered the advice he’d heard from an acquaintance who had been in the military. Crawling along the ground to dodge the bullets that whistled overhead, he managed to reach a creek and hide among rocks until the rebels belonging to the Gabriel Galvis mobile column left that remote rural hamlet in La Gabarra, Norte de Santander.

"It was a miracle, the work of God. Anyone else would be crazy with all that my eyes have seen," he says today. The FARC had left a grotesque scene behind them: 34 scrapers - as coca leaf pickers are often called - killed with shots at point-blank range or with their throats slit.

Days later, FARC admitted to the massacre in a statement on its website in which it accused the 34 victims of being "narco-paramilitaries" and "dogs of war", justifying their murder as part of "the relentless combat that our guerrilla organization is waging against the military-paramilitary forces of the fascist Colombian regime". The media, added the guerrillas, "try to confuse public opinion by presenting them as peasants, coca growers, and as an example of the armed insurgency’s brutality".

In mid-2021, seventeen years later, several top commanders of the now-defunct guerrilla group finally admitted the crime before their victims' families and four survivors. "It’s a crime that shames us. Our objective was to halt a paramilitary advance, not to massacre coca pickers. It should never have happened," Rodrigo Londoño, the FARC's last commander-in-chief and better known by his nom-de-guerre 'Timochenko', told them. In two private meetings, mediated by the TRC, they asked them for forgiveness and admitted that the truth of what happened was the one relayed by survivors and not the one they’d stuck to for over a decade.

Blind spots of a confession

FARC’s contrition was a relief for victims of La Gabarra. However, the extent of their acknowledgment is still not satisfactory for many, who feel that the former rebels continue to minimize their cruelty that day and the reasons that led them to commit the massacre. By presenting it as the uncommunicated work of a mid-level commander, Almir Duque, who didn’t follow the organization's rules (and who, moreover, died in combat afterwards), they feel that the FARC leadership continues to evade its share of responsibility and avoids answering their most difficult questions.

There are several truths they believe are obscured by what they see as a half-confession. First, they insist that the rebels never bothered to check whether the people on the farm were actually paramilitaries or whether their information might be wrong. Second, that they not only shot them, but also slit their throats. And third, that the operation was part of a dispute over control of the cocaine trade in the Catatumbo region. The sum of these facts, they feel, proves that the massacre was premeditated and not a decision made in the heat of the moment.

In his first meeting with the FARC leadership in July 2021, Esteban complained about their initial insistence that his men only shot the hostages after one of them escaped. "So it was all my fault?" he told them. "Why did I decide to flee? Because I’d already seen with my own eyes that they were slitting people's throats. Were I to let them tie me up, I knew I’d suffer the same fate," he told Justice Info, evoking the terror that had already seized him in 1999 when paramilitaries forced him off a bus and kept him tied up for several hours.

"Why did they never inspect the rooms to check for weapons and uniforms, to see if they were really paramilitaries?" asks Cristo Quintero. All of the victims that day were humble peasants. Four of them were teenagers. One was his 16-year-old son Jhon Jairo.

End of a 17-year oblivion

Despite the limitations they see in the FARC's remorse, victims defend their 18-month work with the TRC, which allowed them to meet each other and reconstruct many details of a massacre that, as Jhon Jairo's sister Paola says, "was sunk in silence".

For the Quintero family, meeting Esteban and the other three survivors allowed them to learn about the circumstances in which Jhon Jairo died. They were unaware of them because they lived for 20 years in the Venezuelan state of Apure, after being forcibly displaced from Catatumbo in 2000 following threats from the paramilitaries, who had already killed another of their sons. Physical distance and financial difficulties prevented them from coming to the funeral and they only returned to Cúcuta two years ago, after the social and humanitarian debacle in Venezuela. The TRC, whose existence they were unaware of until it sought them out, allowed them to express their pain to FARC’s top brass. "We were able to tell them how we felt that they took a piece of our lives away from us. We rested because all of this was holed up inside us," says mother Paulina Hernandez.

In addition to asking that the FARC clear their relatives’ names and underscore that they were not paramilitaries, victims of La Gabarra have requested material redress, given that most are humble families who were deprived by the guerrillas of family members who in many cases represented their livelihood. Jhon Jairo's parents, aged 78 and 70, have no pension and one of them receives a government subsidy for the elderly amounting to 80,000 pesos (US$17) a month.

"They don't know what we had to live through to survive, how many of us had to leave and what we did to get back on our feet," says Esteban, who has not since returned to the region. "If they were really committed to recognizing their victims and it’s true that they handed over their money to the State, as they say, then they should pressure the State so that it really reaches victims. We need deeds, not just words”. That dissatisfaction is what led the victims' group to reject a third closing meeting with FARC leaders this year.

A shelved documentary

There is another, more symbolic element of redress that the victims of La Gabarra are still waiting for, but this time from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Over the last year they have been working with TRC officials on a documentary that, through animations and oral testimonies, tells their story. It was due to be released in August. For reasons they do not understand and despite their repeated questions, the 43-minute film has not yet seen the light, even though – as three people confirmed to Justice Info – it’s been ready for several months.

"It should have been the end of this process, but the Commission closed its doors in August and we’re still waiting. My whole family wants to see it. We want the world to know what happened," says Wilson Prieto, who also survived the massacre after pretending for hours that he was dead. He still bears the scars left by four shots, including one in his forearm that reduced the mobility of his hand and another in his side. Like the other victims, he believes the film could speed up financial redress and doesn’t understand why it was shelved.

Justice Info asked two of the TRC’s former commissioners, its president Francisco de Roux and public health specialist Saul Franco who led its work in Catatumbo, but neither responded whether it will be launched.

The purge of an uncomfortable leader

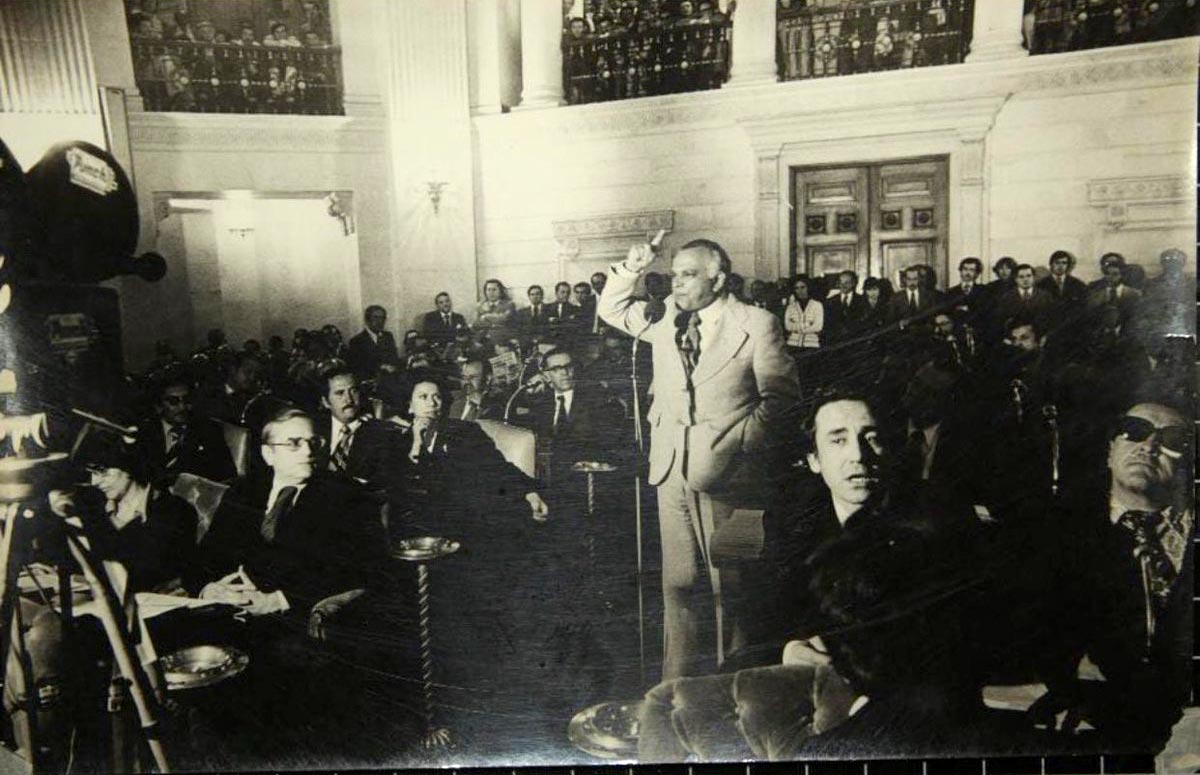

In José Cardona’s case, it’s a crime that FARC has never acknowledged. Throughout the 1980s, Cardona – a devout Marxist-Leninist who visited Moscow and was active in the Colombian Communist Party for almost four decades – waged multiple and lonely fights with his party colleagues to get them to back away from supporting the insurgent struggle. First he insisted that they should give priority to the class struggle, hand in hand with their worker and peasant bases, then he internally denounced that FARC was recruiting communist party-members and, later, that the arrival of guerrilla structures in rural areas where the party was gaining political prominence was hurting them at the ballot box. He himself lost his seat in the House of Representatives in 1982, after serving two terms in Congress. He was finally expelled a year later, branded a traitor and a revisionist, in what his son José Jr., a 58-year old farmer, describes as a purge "in the Stalinist manner". He ended up as a persona non grata after making those complaints public in his book, which José Jr. describes as "a catalyst for his death." The subtitle was telling of its contents: 'A clique corrodes the Colombian Communist Party'.

According to José Jr., two weeks after the assassination, two communist leaders who sympathized with his father came to his house to tell his widow that the perpetrators were members of the FARC's Sixth Front, under orders from its top brass. Decades later, he says, a former rebel relayed a similar version to a researcher he knew. The criminal justice system, however, never had that certainty. For years, the case languished in the files as yet another murder in a troubled country. So much so that it took José, the most obsessed of his brothers to elucidate the mystery of their father's death, years to get the Colombian state to recognize him as a victim of the armed conflict.

"They never address it, it's a taboo"

It’s been José Jr. who has tried to get FARC to respond. He first wrote them a letter in 2014, during the peace negotiations in Havana, but got no response. Four years later, when the former rebels had laid down their arms and were making political runs in their electoral debut, José arrived at a rally in Cali for former commander and current congressman Luis Alberto Albán, also known as 'Marcos Calarcá'. "I’m the son of José Cardona and I come to congratulate you for doing what my father told you thirty years ago to do: to do politics in civility and abandon the armed struggle," he said. Albán did not say anything, but when José Jr. approached him at the end of the event, he says that the former rebel promised him that he’d talk to his former comrades-in-arms. More recently, José tried to meet with Senator Julián Gallo, formerly known as 'Carlos Antonio Lozada,' but he only got a Whatsapp reply stating that it had not been them.

In March 2021 José was invited by the TRC to a dialogue where in theory he would talk with former rebel leader Pablo Catatumbo, a native of Valle del Cauca like his father, but in the end he did not arrive. Political scientist Gustavo Duncan, who has written about the need for the FARC to own up to the truth about its retaliations against factions of the democratic left, asked that same former commander and current senator about the case on a radio talk show, but Catatumbo avoided answering. As Cardona Jr. says, "they never address it, it’s a taboo".

In addition to FARC clarifying authorship of the crime, José Jr. seeks a vindication of Cardona Hoyos’s pacifist legacy and his almost prophetic role. "My father foresaw the rivers of blood. His civilist theses remain valid ever since that window of opportunity for peace in the 1980s was wasted. I may be exaggerating or deluded, but how many deaths could we avoided if his advice had been heeded?" he asks. As he proudly states on his Twitter profile, "history proved you right."

No response from FARC

There is barely a paragraph about José Cardona’s murder in the TRC’s final report, which includes the family's finger-pointing at FARC and the fact that they have never acknowledged it. "This crime illustrates that these differences were also resolved through violence and the physical elimination of the political opponent," the report states, without directly attributing responsibility to the guerrillas.

Justice Info sought out three members of the former FARC to ask them about their discussions on acknowledging Cardona’s murder or further clarifying La Gabarra massacre. Neither Luis Alberto Albán, Julián Gallo nor Pastor Alape gave any concrete element of response.

Despite the lack of answers, José Cardona Jr. is happy that his father's case appeared in the TRC’s report and that the former guerrillas in the end had to listen to him. "I don't hate them, I defend their presence in Congress, that they can engage in politics while not being killed. I don't intend to file legal actions against any of them either," he says from his farm in Valle del Cauca, “but I want them to recognize the authorship of his murder and how wrong they were”.