Prosecuting war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in Serbia means dealing with three different conflicts: the 1991-1995 conflict in Croatia, the 1992-1995 conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the 1998-1999 conflict in Kosovo. In the first two conflicts, Serbia’s political leadership and security apparatus played a key role in creating, arming and supporting secessionist republics in Croatia and BiH. Regarding the conflict in Kosovo, Serbia’s responsibilities arise from the armed repression of the Kosovo Albanian population in Kosovo and subsequent conflict with the Kosovo Liberation Army, the armed faction of the Albanian population. While Serbian authorities were amongst the perpetrators in all these conflicts, ethnic Serbs from Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo currently displaced in Serbia were also amongst the victims. This creates several options for Serbian and other prosecutors of the region when tackling war crimes: applying limited territorial jurisdiction as regards where crimes were committed, implementing regional cooperation, or taking into account the nationality of victims or perpetrators, keeping in mind that both victims and perpetrators often enjoy double citizenship and might be living in a different country in the region.

Domestic prosecution of war crimes in Serbia started in 2003, three years after the ousting of Serbia’s wartime leader Slobodan Milosevic. At that time, the new authorities in Belgrade were eager to regain international credibility after the conflicts of the 1990s, when Serbia faced sanctions and international isolation. The transition was, however, incomplete and relied on uneasy and unstable political coalitions. Large parts of the security sector, including the police, armed forces and internal security services were not touched by the reforms and they enjoyed the support of some of the new political actors. Large sections of Serbian society believed that Serbia had been the victim of external forces, who conspired to break up Yugoslavia. Due to the lack of media freedom, there was little or no knowledge of the crimes committed by the separatist Serb republics in Bosnia and Croatia or by the Serbian forces in Kosovo.

Back to the 1990s?

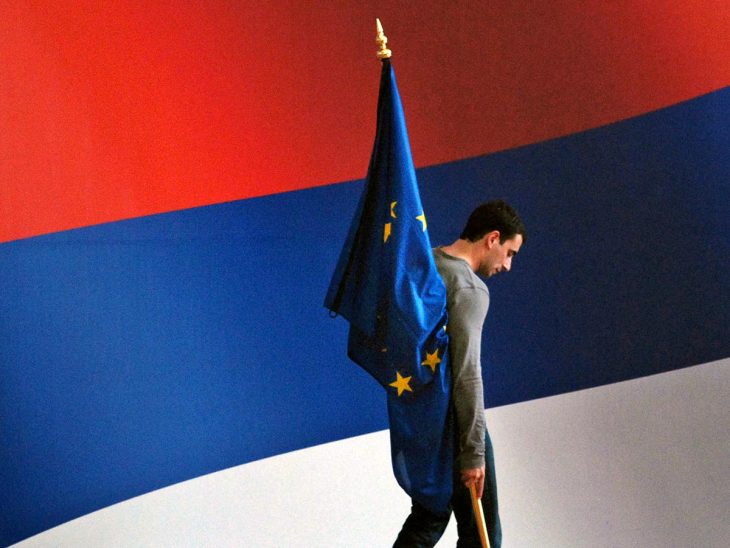

In parallel to the political transition, Serbia initiated the process of accession to the European Union (EU). Under this process, Serbia is required, inter alia, to reform and democratise its institutions. After a few years of moderate progress in the early stages of the EU accession process, the political forces that were dominant in the 1990s managed to stage a gradual return to power following the 2012 elections. This raised concerns for the process of EU accession. The new government initially claimed to have reformed and made commitments to continue along the democratic path. However, as time passed, their most authoritarian and undemocratic trends surfaced again, in particular after Aleksandar Vucic, former Minister of Information under Milosevic, became president in 2017 and his party obtained 188 seats out of 250 in parliament in 2020. As a result, while five years ago Serbia was considered a free country, today it is considered only partly free by the Freedom House organization. Following years of constant decline, its position in the 2020 Democracy Index established by The Economist was worse than the one in 2006. Serbian society appears divided between progressive, pro-EU aspirations and more traditional and nationalist values. Many observers expressed concern that the country’s politics had returned to the 1990s. The unsolved issue of Kosovo that Serbia still considers part of its territory is keeping tensions alive and fuelling nationalism.

War crimes prosecution linked to EU accession

The domestic prosecution of war crimes was directly affected by the internal power dynamics in Serbia. The whole process can be divided in two distinct phases.

A first phase covers the period between 2003 and 2015. It coincides with the creation of the War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office (WCPO), the War Crimes Investigation Service (WCIS) and a special department at the Higher Court and Court of Appeals in Belgrade as first and second instance courts dealing with war crimes. This period was characterised by an initial lack of independence of the judiciary, regular attacks on the WCPO by local politicians and repeated calls for its closure since it refused to conduct trials in absentia of foreign citizens, i.e. mainly Albanians, Bosniaks (Muslim Bosnians) and Croats allegedly responsible for crimes against Serbs.

During this period, as reported by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), 60 indictments were filed and a total of 162 persons were charged, which resulted in 41 cases and 49 different trials (courts sometimes held separate trials for different defendants in the same case). Out of those, 27 trials were completed, resulting in the conviction of about 60% of the defendants. The remaining trials were pending either in first or second instance.

However, it is worth recalling that out of those 41 cases, 10 had been transferred from other countries, mostly from BiH after a full investigation had already been conducted in the country of origin. According to the OSCE, the WCPO started approximately three investigations a year and each prosecutor at the WCPO initiated an investigation that resulted in a trial every three years. Similar findings were reached also by other organizations following the issue. The Humanitarian Law Center (HLC), a leading Serbian NGO monitoring war crimes issues, concluded that the lack of efficiency in the investigations was due to lack of resources and often poor cooperation by the WCIS. In addition, the organization found an excessive focus on low-ranking perpetrators in the police and in the military, while high-ranking officials were not prosecuted. Similar issues were raised by Amnesty International (AI), which noticed the lack of political will and strategy to prosecute war crimes in Serbia and poor coordination amongst state bodies.

The HLC and AI urged the European Union not to miss the chance of the EU accession process to make sure that Serbia would take a strategic approach to war crimes prosecution and eventually accelerate the pace of prosecutions and trials. HLC went as far as elaborating a model strategy for the prosecution of war crimes, which served as blueprint for the first strategy. Late 2015, the Serbian authorities eventually agreed that this was a necessary step and progress in the prosecution of war crimes became part of the EU accession process.

Disappointing performance since 2016

This opened a second phase in the prosecution of war crimes, following the adoption in February 2016 of the first strategy to deal with war crimes covering the period 2016-2020, when a second strategy was adopted for the period until 2026. The strategy considered the prosecution of war crimes as one of the most important steps to achieve lasting peace and reconciliation in the region. It acknowledged the shortcomings of the previous approach, especially the lack of cases against high-ranking perpetrators. It was complemented by a specific strategy for the office of the prosecutor, which set forth important priorities to guide the work of the prosecutors for the period 2018-2023. In particular, prosecutors were requested to prioritise crimes of particular gravity, crimes where alleged perpetrators were high-ranking individuals, crimes where evidence was available and where there was the possibility to activate regional cooperation with neighbouring countries. In the document, the prosecutors’ office rejected the conduct of trials in absentia, although in her separate work plan, war crimes chief prosecutor Snežana Stanojković didn’t exclude this possibility in principle. The strategy, however, didn’t make any commitment about a specific date for its completion.

Even after the adoption of the strategy, the performance of the prosecutors’ office and of the courts didn’t improve. Despite an increased number of deputy prosecutors and personnel, no significant progress was reported. The number of confirmed indictments for the period 2016-2020 remained extremely low, with 31 indictments in total, including 23 transferred from BiH, and only eight originating from Serbia. Things didn’t change in 2021: only seven indictments were filed, including four indictments transferred from Bosnia. During this period the Higher Court delivered a total of 23 first instance judgements (18 from 2016 to 2020 and five in 2021), while the Court of Appeals issued a total of 29 final verdicts (23 from 2016 to 2020 and six in 2021). The rate of convictions seems to be above 70%, although available data is confusing.

Lack of regional co-operation

These numbers are particularly low if we compare them to the 1,731 cases that are at the pre-investigative stage. The lack of clear prioritisation criteria is widely regarded as one of the main problems. “Instead of tackling cases with large numbers of victims or higher-ranking perpetrators in the army and police, the prosecutor’s office works on cases with just a few victims,” says Ivana Žanić, executive director of the HLC. UNDP transitional justice specialist Ivan Jovanović points to regional shortcomings: “Prosecutors in the region should have common criteria on how to prioritise cases in a strategic way, rather than taking cases on a chronological basis or simply choosing less complex cases.” While Serbia has so far refrained from conducting trials in absentia, the persistent refusal of the Croatian authorities to cooperate on specific cases – i.e. those related to the 1995 Operation Storm when Croatian forces regained territories occupied by a Serb separatist republic – and the current pressure by politicians and public opinion, might push Serbian authorities to conduct such in absentia trials. One of such cases is currently under review before a court in Belgrade and it’s unclear whether the case will move forward. Starting trials in absentia, as Croatia has been doing for a while,is a very worrying signal for regional cooperation on war crimes: the prosecution of foreign citizens in Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia would easily lead to a politicisation of war crime trials. In June 2022 Serge Brammertz, the chief prosecutor at the UN’s Hague based International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals, warned about this when he said that Croatia’s “political decisions to block the justice process” are interfering with regional cooperation.

Impact of the war in Ukraine and tensions in Kosovo

Similarly to what is happening in Bosnia, there is an ongoing process in Serbia aimed at glorifying war criminals. Until recently, convicted war criminals have been sitting in Parliament and they are regularly invited on pro-government TV programs, or publish their memoires. Dangerous rhetoric reminiscent of the 1990s is surfacing again. On the occasion of the final conviction for genocide of former Bosnian-Serb military leader Ratko Mladic by a UN court in 2021, the main political leaders in Serbia clearly stated that it was a judgement imposed on the entire nation, a sort of revenge against the Serbian people and that the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia had been created to put Serbs on trial. In 2022, the war in Ukraine – Russia is a traditional ally of Serbia – and tensions in Kosovo exacerbated nationalist feelings and animosities towards the “West”. This further polarised society, with large parts of Serbia supporting Russia and with decreasing support for EU accession.

In this context, it seems domestic prosecution of war crimes remains confined to a technical exercise, i.e simply “ticking boxes” for the sake of EU accession, with very few cases processed and without real impact on society, while victims, witnesses and perpetrators are ageing and dying. It remains to be seen how much importance the EU will attach to delays in actual implementation of the strategy. Worse, if trials in absentia were to be organized, they may be seen as a tool to foster nationalism and create more tensions in the region rather than promoting reconciliation and lasting peace.