On October 13th, 2022, an Indonesian man, wearing a golden suit with a black velvet peci (Indonesian traditional cap), stood in front of the Amsterdam Court of Appeal. Before him, a black leather case with a sticker that read: ‘Black Pete is racist.’ [referring to the black companion of Saint Nicholas in Dutch folklore] He looked the judges straight in the eye when he spoke: ‘I am delighted to stand here in front of indigenous, white native counselors.’ It is unknown whether they were indeed indigenous to the Dutch land, but that was not the point. By reversing the use of the word inlanders (natives) to address representatives of the Dutch legal system, after all a white institution of power, he reminded them of the condescending way that Indonesians were treated during colonial times. For Indonesians, the word ‘inlander’ is a slur, perhaps similar to what the n-word means to people of African descent. He continued to explain that within the 350 years of Dutch colonial rule, Indonesians were never given the legal rights that he now got.

The man is named Jeffry Pondaag and he is the founder and chair of the Komite Utang Kehormatan Belanda (KUKB, Committee of Dutch Honorary Debts). It was not the first time that he made use of the rights that his ancestors did not have. His organization is known for the successful court cases against the Dutch state regarding the 1947 massacre in the West Javanese village of Rawagede. After they won the first series of lawsuits in 2011, they continuously brought more cases to the Dutch court.

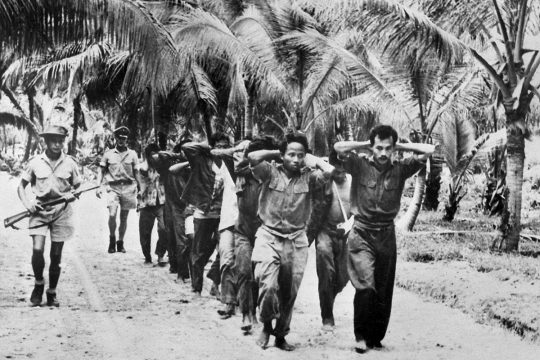

For years, Pondaag fought for the rights of his fellow Indonesians who were brutally murdered, tortured or raped by the Dutch (colonial) army during the country’s independence war that lasted from 1945 until 1949. His efforts did not go unnoticed.

The gruesome facts that the cases brought to light also alarmed historians and journalists who wondered whether this was just ‘the tip of the iceberg’. Clearly, the KUKB court cases opened a Pandora box and put the sensitive topic of Dutch war crimes against Indonesians back on the agenda. However, instead of being acknowledged for his crucial role, Pondaag is often ignored and sidelined from discussions in the Netherlands, as he is considered too radical.

What bersiap stands for

In the court case of October, however, the accused was not the Dutch state, but the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. In January 2022 KUKB had reported the Rijksmuseum, the curator Harm Stevens and director Taco Dibbits to the police. Their crime? The persistent use of the term ‘bersiap’ in the exhibition Revolusi Indonesia Independent (February 11 – June 5, 2022), which focused on the Indonesian independence war.

Not just Rijksmuseum but Dutch historians in general use the word ‘bersiap’ to indicate an outburst of anti-colonial violence that took place during the early phase of the revolution in 1945-46. In the Dutch context ‘bersiap’ stands for brutalities that were committed by Indonesians against Dutch, mixed-race Indo-Dutch and those who collaborated with the Dutch.

However, according to KUKB, the whole concept of bersiap is a Dutch colonial invention that only exists within Dutch history books. They maintain that the bersiap as historical period – often described as an isolated event in time of unilateral anticolonial violence from Indonesians against the Dutch – does not exist. During the same months that the Dutch claim that there was bersiap, Dutch and Allied forces committed acts of violence as well. The term also feeds the denial of the colonizers who do not want to see themselves as aggressors, occupiers of other people’s land. Instead, the Dutch interpretation of bersiap creates the impression of a regular conflict where two rival nations are equally guilty of the violent escalation. Bersiap thus stands for the colonial frame of ‘both sides.’

Exposing anti-colonial violence in the Dutch context also ties in with racist orientalist ideas of Indonesians being generally kind and submissive but nevertheless capable of sudden and (at least for the colonizers) unexpected brutalities. Take for example the 1989 publication of Dutch historian Lou de Jong in which he explained the bersiap through the “nature of the Javanese”, whom he described as being known for their “smoldering aggressiveness” that could pop up unexpectedly. More recently the headline of an op-ed piece in Dutch daily NRC read: “I need to understand the blood-thirsty Indonesian fighter.” As if bloodthirstiness and not the re-occupation was the motivation for Indonesians to take up arms against the Dutch.

At first, the Dutch Public Prosecutor (OM) rejected KUKB’s police report, based on the argument that the bersiap could be explained in different ways and that the term was not inherently offensive to Indonesians in general. They deemed it a non-legal issue that had to be solved through open debate within society. KUKB then submitted a complaint. Via a special legal procedure, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal was forced to examine the case and set up court hearings to listen to all parties involved. KUKB maintained that the Rijksmuseum had insulted Indonesians as a group.

Lack of Indonesian representation

At the court hearing, Pondaag was accompanied by another Indonesian, Dida Pattipilohy, then secretary of the foundation. The appearance of two Indonesians in front of a Dutch court is quite exceptional. Indonesians are hardly represented in the Netherlands where they form a very small minority. Instead, those who identity as Indische Nederlanders (Dutch-Indies people) are dominantly present. They are of mixed Indo-European descent whose ancestors, during colonial times, were legally assimilated to Europeans. Their special legal status, which equaled Dutch citizenship, is the reason that they left Indonesia after the country became independent in 1945.

Another big minority group present in Dutch society are people who identify as Moluccan. They originate from the East Indonesian province of Maluku. During colonial times, their fathers or grandfathers collaborated with the Dutch by joining the colonial army. They in fact helped to commit the crimes that KUKB brought to court.

As a result of the dominance of pro-colonial groups, the voices of the formerly oppressed, such as the Indonesian relatives represented by KUKB, are often not taken into account in public debates in the Netherlands. The attitude of the Rijksmuseum and the handling of this case illustrated this clearly.

An important point is that curator Stevens, and also director Dibbits, were informed about the problems with the Dutch concept of bersiap beforehand. In June 2021, after Pondaag had criticized another Rijksmuseum exhibition, Stevens invited him, Pattipilohy and her 96-year-old mother for a talk. During this meeting the plans for the upcoming exhibition ‘Revolusi’ were extensively discussed. Again and again they emphasized that the idea of the bersiap as a separate period did not exist for Indonesians, as 350 years of Dutch colonialism had preceded 1945, which were followed by a bloody re-occupation war that lasted until 1949.

In fact, KUKB only went to the police after an op-ed piece by an Indonesian guest curator caused a stir. In January 11, 2022, one month before the opening of the exhibition, Bonnie Triyana published an opinion piece in Dutch daily NRC in which he announced that the Rijksmuseum would not use the term ‘bersiap’ anymore because of its racist connotation. It did not seem that Triyana was just sharing his personal opinion, because the next day, during the online press conference when curator Harm Stevens was asked why he had chosen to avoid the term bersiap in the exhibition, he did not deny that this was the case. He only assured that they were nevertheless paying attention to the topic of anticolonial violence as such.

The point is that the museum officials did receive Triyana’s piece up front and did not distance themselves from him, until the situation got out of hand and they received angry messages from right-wing people, accusing them of following ‘the woke-agenda.’As opposed to Pondaag, Triyana (who lives in Indonesia) is not at all seen as radical. He does not seem the type to have deliberately caused this controversy. He was perhaps as shocked by the responses in Dutch society as the museum staff itself. But it was Triyana who was ‘thrown under the bus’ by the museum officials as if he had done something wrong. After the Federatie of Indische Nederlanders (FIN, Federation of Dutch-Indies people) reported him to the Dutch police, the Rijksmuseum publicly distanced itself from Triyana’s statement. Director Dibbits, perhaps afraid of bad publicity, said that it was just Triyana’s personal opinion. He went on to deny that the term was racist and promised they would continue to use it. He also explicitly stated that the Rijksmuseum was “not woke.” All this led to KUKB’s decision to report Rijksmuseum to the police.

Taking sides

This is where the pain is: Dibbits immediately listened to Dutch-Indies people with openly colonial ideas, but dismissed Indonesians who addressed racism. The latter is a continuation of colonial racist hierarchies where Dutch-Indies people were closer to the colonizers than Indonesians, who were considered ‘inlanders’, natives, people you did not have to reckon with.

Last week’s rejection of the ‘bersiap-case’ shows that this goes much further than Dutch-Indies people and prevailing colonial ideas. This is about a white system of power not willing to face the facts: the Amsterdam Court of Appeal, the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch Public Prosecutor, they are closing ranks, not used to empowered Indonesians who stand up and use the law in their advantage. The short text of the verdict by the Amsterdam Court of Appeal only echoes the simplistic arguments that the Prosecutor had used in defense of the Rijksmuseum. No single word about the sensible arguments that KUKB had put forward during the hearing. Pondaag responded: “the Dutch praise themselves for having a democratic constitutional state, but what I see is that white natives protect each other and ignore what Indonesians say.”

Marjolein van Pagee is an independent historian based in the Netherlands, specialized in the history of the Dutch occupation of Indonesia. She is the author of “Banda. De Genocide van Jan Pieterszoon Coen” (Banda. The Genocide of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, 2021). Van Pagee is the founder of the Histori Bersama Foundation, an online platform that provides Dutch-English-Indonesian translations of articles on Dutch colonialism in Indonesia. Since 2012 she actively supports the work of the KUKB foundation. Before the Court of Appeal of Amsterdam, she both testified as an expert witness and defended the KUKB.