After hearing elders, community leaders and experts in December, the Yoorrook truth-telling commission restarted last week its public hearings on one of the most impacting violations faced by First Nations people in the state of Victoria, in Australia: those done to children.

In a pre-recorded session aired before the commission on Wednesday March 1, members of the Wright family from Heywood in south-western Victoria told the story of their mother, Eunice, who was forcibly removed by police at the age of nine in the 1950s, along with her siblings Ronnie and Gloria. At the time, Eunice’s mother was away in hospital with terminal tuberculosis. “They were having afternoon tea [at her aunt’s]. It was hard enough with their mum in hospital, but they were safe and well-loved. That’s when the police came,” recounted her daughter Donna. Another aunt, she added, hid six year-old brother Ronnie under a bed when the police came. “If you don’t tell us where Ronnie is, we’re going to come and take your children,” said an officer, according to Donna’s testimony before the Yoorrook Commission.

The three children were held in cells at the police station and taken before a magistrate, who approved the separation of the children from their mother, despite the protests of the other family members: “The decision was already made,” said Donna. At a receiving centre for children in state care, the two girls [Eunice and Gloria] were separated from Ronnie, reduced to meeting him through a fence once a day. Donna told the Commission that “they’d meet at the fence and sent kisses to each other. The separation traumatised mum all her life – she always spoke about speaking to him through the fence.”

The children were processed under criminal forms. Blatantly racist comments were made in official records, which were obtained by the Wright family, about the children and their parents. “They came from home – safe and loved and happy – to this environment where they’re not even treated humanely, and this system starts changing their identity. They are now these other children, they’re not Eunice and Ronnie and Gloria. They’re now this piece of paper that this government used to change their identity and who they were,” said Donna.

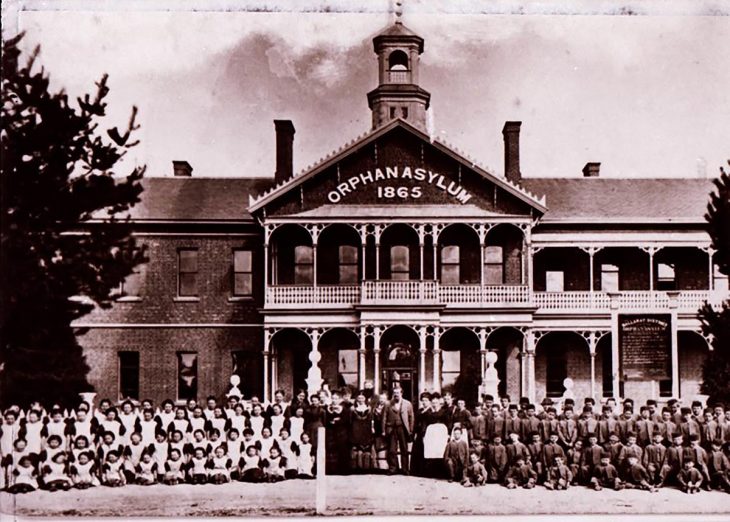

Orphanage “little slaves”

The orphanage in Ballarat, where Eunice was taken and put to work, “wouldn’t have been able to run without their little slaves,” she added. And violence was common. Ronnie – who, like other boys in state care was sent out to work on farms, had his jaw broken after being hit by one farmer, she said. After losing her hair ribbon, Eunice had her head rammed into a steel coat hook by a member of the orphanage staff. It was only decades later after her daughter discovered a long scar on her mother’s head that Eunice told her the story. In both these cases, no medical records of these serious injuries exist.

The Wright family members told the Commission of the enduring effects of separation. Eunice’s father, Monty, “never recovered” from the removal of his children and “died of a broken heart” aged 53 in a psychiatric hospital, suffering from malnutrition and bed sores. His wife, a regular visitor, was not informed of Monty’s death until she visited one day, and was told her husband had been buried in a pauper’s grave. “He was just left in that hospital to rot, and not treated like a human. How much trauma do you inflict on one person?” asked Donna Wright. Ronnie died young, and a generation later, three out of five of Gloria’s children committed suicide, affected by their own separation from their mother.

Despite the violence and trauma inflicted upon her family and years of activism, Eunice Wright never saw any form of compensation from the Victoria government, passing away four days before Victoria became the last Australian state in March last year and announced a redress scheme for survivors of the “stolen generations” – i.e. the children who were forcibly removed from their parents under official government policy. Eunice’s family is unable to apply for reparations on her behalf because she died days before the announcement. “I feel like the government pissed on our family tree,” said another of her daughters, Tina. “Here in Victoria, not only did they do nothing, they didn’t care,” added Donna.

“This is happening right now”

On Thursday, Sissy Austin, a DjabWurrung woman, gave evidence to the commission of her own experiences with the contemporary Victoria child protection system, after becoming at the age of 21 a carer for her younger cousin, Tinjani, only seven years ago.

In open session, Sissy Austin decried the lack of support given by child protection authorities to both herself and her cousin, because of their Aboriginal origins. Tinjani ended up with Sissy after leaving an unsafe placement she had been put in by the Department of Families, and calling her cousins from a train station telephone. Sissy received “no support at all” for the first two years she cared for Tinjani, moving houses ten times in five years, and struggling to negotiate various bureaucratic hurdles. On one occasion, Tinjani was removed from school because Sissy could not be confirmed as her official guardian. And when support finally arrived, it was often unhelpful, Sissy said. Officials were unable to name Tinjani’s traditional country, for example. “That was a kick in the guts: ‘currently unknown’. She’d been with me for a number of years and seen so many [social] workers. All it would’ve taken was asking us,” Sissy testified.

The grief of separation described by the Wright family and endured by many Aboriginal families at the hands of government continues today, said Sissy Austin. “I’ve heard these stories from our elders, but what we don’t realise is that this is happening right now: there are children in our community who know they’ve got a sibling somewhere, they just don’t know where because they don’t have a voice.” Attempts to secure funding from the Department to cover travel costs for sibling visits have been unsuccessful, and Austin recommended this to the commission as an area for reform.

An “us and them” attitude pervade the relationship between the Department and Aboriginal mothers, she added. “The dehumanisation of Aboriginal mothers is quite frankly disgusting,” she continued. The punitive nature of the system leaves women afraid to report domestic violence for fear of child removal, she said, and the involvement of the courts – “the most dehumanising place you can enter into” – makes Aboriginal women “feel like the villain of their story.” At the end of her testimony, Sissy Austin implored the Department to view Aboriginal women as loving mothers, rather than problems.

93% of Aboriginal children criminalized

Due to the sensitivity of the topics covered by the commission, much of the evidence was heard in closed sessions. But on Friday, a range of Aboriginal-led organisations spoke to the commission about Victoria's child protection system.

Chris Harrison from the Aboriginal Justice Caucus, an NGO that provides state-wide Aboriginal representation before the justice system, told the Commission that 93% of Aboriginal children were leaving the child protection system with a criminal charge to their name, decrying the criminalisation of vulnerable Aboriginal children in care. Harrison explained that the threat of police is regularly used as a tactic to keep children in line, and that the Department often seeks to have Aboriginal children in care charged for minor incidents, such as breaking a window, so insurance can be claimed on damaged items.

Anoushka Jeronimus of WEstjustice, an organisation that provides free legal help to people in the western suburbs of Melbourne, told the commission that it is “increasingly common for police to be first responders,” as stand-in youth workers or counsellors, and that this also contributes to the criminalisation of Aboriginal children. Such interactions for minor incidents can be “counterproductive and re-traumatising” for children who have already had negative experiences with police. Police racism, she said, was a further contributing factor in Aboriginal children’s continued over-representation in Victorian incarceration rates.

2021 data from the Victoria Commission for Children and Young People, a state monitoring body, found that Aboriginal children were nine times more likely than non-Aboriginal children to be in youth judicial custody. Police were also more likely to use detention rather than cautions with Aboriginal children, it said, and courts were more likely to issue longer sentences to them. Also, the bail laws, which have had the effect of doubling the number of Aboriginal women in custody, have contributed to a situation where Aboriginal children “are losing their parents at a greater rate than they were last century,” a representative of the Koorie Youth Council, an Aboriginal youth organisation, told the commission.

These three days of testimonies on the child protection system shed a cold light, according to what the Yoorrook truth-commission was able to make public, on the fact that the injustices of the past continue to be repeated in contemporary Victoria. The commission will reconvene this week for hearings on Victoria’s criminal justice system. It has also scheduled a series of hearings at the end of March where Victorian government authorities will be invited to respond and give their version of the facts.