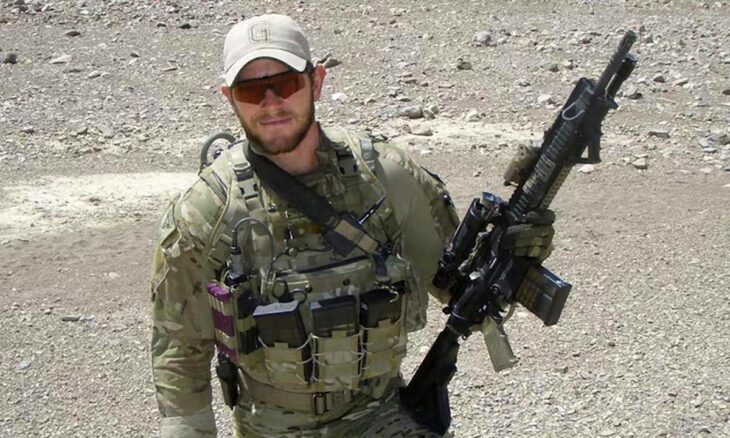

Last Monday, 20 March, former SAS trooper Oliver Schultz, who was awarded the Commendation for Gallantry for his service in Afghanistan, was arrested and charged with the war crime of murder in relation to the killing of an Afghan man, Dad Mohammad, in May 2012. The maximum penalty for the offence is life in prison. Prosecutors will allege that Mohammad “was not taking an active part in hostilities”, and that Schultz “knew, or was reckless as to the factual circumstances establishing that [Mohammad] was not taking an active part in the hostilities.”

On 28 March, Schultz was granted bail ahead of a trial expected to take place in 2024 or 2025. The criminal investigation followed a shocking report in November 2020 that found evidence of serious abuses possibly amounting to war crimes by members of the Australian Special Forces in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016.

The arrest marks the first time a member of the Australian Defence Force has been charged with a war crime under Australian law. Given the lack of precedent for war crimes prosecutions in civilian courts or comparable jurisdictions, combined with a lack of local experience in the area and the formidable difficulties of obtaining admissible evidence from Afghanistan, prosecutors will most likely face unique difficulties in proving the offence to the requisite degree in front of a jury. The only previous attempt to prosecute defence force members for conduct in Afghanistan failed, when manslaughter charges laid against two soldiers through the military system were thrown out in 2011 when a judge ruled that the accused did not have a duty of care in relation to civilians killed in a raid by Australian troops.

The Schultz case is however backed this time by a significant body of pre-existing investigation and a specifically dedicated organisation in the form of the Office of the Special Investigator, created in January 2021. A large proportion of its work has pertained to the examination of incidents referred for criminal investigation in the 2020 Brereton Report. According to the bar set by Brereton in his report, referrals were only made where there was a realistic prospect of gathering sufficient evidence to charge individuals, while regard was also had to the prospects of conviction. Significant resources have been devoted to the investigation – in the Schultz case, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) has reported that a dedicated team including homicide detectives and an intelligence officer examined the relevant incident for more than two years.

A “straightforward” case?

Melanie O’Brien, Associate Professor of International Law at the University of Western Australia, says that “the prosecution would not have brought charges if they didn’t already have sufficient evidence.” Indeed, with strong visual evidence already in the public domain, O’Brien suspects that the Schultz case may be more “straightforward” than other future war crimes prosecutions.

It is notable that the first arrest of a war crimes suspect has come in relation to one of the most public and vivid elements of the war crimes controversy. In March 2020, the ABC broadcast footage of Oliver Schultz shooting Mohammad, a father of two, through the head and the heart while he lay on the ground in an Uruzgan wheat field after being mauled by an SAS dog. The graphic helmet-camera footage, which shows Schultz calling “Do you want me to drop this c***?” to a colleague, before firing his weapon at Mohammad from point-blank range, became the shocking collective image of special forces misconduct in Afghanistan. It is unusual in an investigation into military personnel, constrained by security classifications, that such a clear and significant piece of information could be in the public domain, alongside interviews with family members of the deceased and further allegations carried by the media against the accused.

Between 40 and 50 acts investigated

As a first prosecution, much rides on the Schultz case. The Office of the Special Investigator told Parliament in February that it is investigating between 40 and 50 alleged offences by Australian special forces in Afghanistan, but that no further charges are expected for some time. O’Brien says that a successful war crimes prosecution may place pressure on Coalition members to take war crimes investigations seriously, and question an inclination to conduct prosecutions militarily rather than in civilian courts out of a view that military courts “know what it’s like in the theatre of war.” She adds that, in London, days after the arrest of Oliver Schultz, Lord Justice Sir Charles Haddon-Cave opened an independent inquiry into allegations that members of the UK SAS were involved in the suspicious deaths of 54 Afghan civilians in 2010 and 2011, and that illegal activity may have been covered-up or inadequately investigated. O’Brien says that the Australian war crimes investigation has positioned the country as “a global leader in taking accountability” and that it may demonstrate that “you can hold those who have committed war crimes accountable while continuing to function as a military, and become more effective because of it.”

Much of the ongoing effectiveness of Australia’s war crimes investigations will ride on the success of the Schultz prosecution. If a conviction cannot be secured in the first instance, it may make it more difficult to bring future cases with greater levels of ambiguity to trial, especially given the novel status of the offence in Australian courts.