On March 16, Italy’s Council of Ministers, the executive organ of the government currently led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, unexpectedly cut down a long-awaited bill put forward by the Ministry of Justice. The drastic cuts that were made leave out the qualification of crimes against humanity, narrow the scope of war crimes and genocide, as well as the scope of the application of universal jurisdiction – whose implementation is only now being introduced, 20 years after the Rome Statute entered into force.

Italy will thus remain an almost isolated case in Europe. Since the International Criminal Court (ICC) started operating in 2002, state parties to the court have committed to incorporate its core crimes in their national legislations, namely crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide and - since 2010 - the crime of aggression. This informal obligation for the Rome Statute signatories responds to the principle of complementarity, which gives priority to national courts, and aims at facilitating states cooperation with the Hague court.

Ukraine: a wake-up call

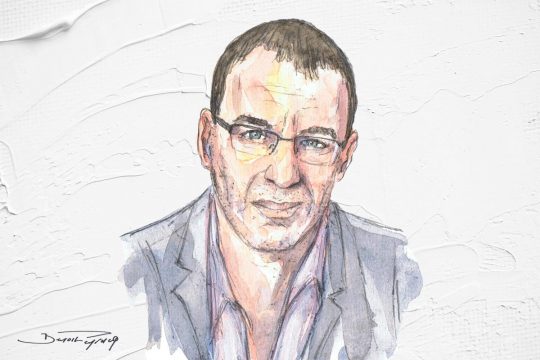

In February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, cooperation on international crimes suddenly became all the more relevant to European states. “It was like a wake-up call, for many the war was a bit closer to home,” says Philip Grant, founder and executive director of TRIAL International. In an in-depth interview in November 2022, he told Justice Info how it has accelerated a revival of universal jurisdiction. Germany, Spain, Sweden and other European states have swiftly opened investigations for the alleged crimes committed by Russia. But Italy is lacking the necessary legislation follow their example.

To fill this gap, the previous government appointed a commission. This was created in March 2022 by former Justice Minister Marta Cartabia and chaired by two well-established Italian law professors, Francesco Palazzo and Fauso Pocar. “We worked very quickly to draft the 80 articles that could make a homogeneous code for all four international crimes,” says Chantal Meloni, professor of international criminal law at the University of Milan and member of the commission.

On March 20, just a few days after his bill was mutilated, the current Italian Justice Minister Carlo Nordio attended a conference in London, which gathered world Justice Ministers in support of ICC work in Ukraine. He renewed Italy’s backing of the Hague Court, underlining that all he could offer in the field of cooperation was the country’s “know-how” in fighting mafia and international organised crime.

A choice from the top?

“It is true that Italian prosecutors are very well equipped to conduct complex investigations,” says Meloni. “But the definition of these crimes is missing. The prosecutors have to use ordinary offences that don’t capture the gravity, the systematic dimension and the link to the state policy. Judges and prosecutors in Italy are eager to start working on international cases. It’s not expertise that is missing but political will.” There have been attempts to regulate these crimes in the past, she explains, but this was the first significant draft in 15 years and the first to make it that far.

When the Mario Draghi government fell last July, there were fears that the bill would be dropped. But new Justice Minister Nordio created a smaller working group, including ICC judge Rosario Aitala, and moved forward with the law reform project. The text gathered the consensus of the Defence and Foreign Affairs Ministers and the approval of the chief military prosecutor. This last step seemed the most delicate, as military courts have in the past hindered similar bills to maintain control over the prosecution of war crimes. However, a compromise was found, leaving crimes committed by the military to their jurisdiction and putting all other war crimes in the hands of civil courts.

“That March 16, we took the approval of the bill for granted,” says Meloni. But the bad news came in the form of a short press release announcing a new amended draft law with no mentions of crimes against humanity or genocide. The Council of Ministers had drastically changed the text. What happened is not clear, says Chantal Meloni, but “it appears to have been a Council Presidency’s choice” [i.e. Giorgia Meloni].

Crime of aggression and universal jurisdiction

The amended version of the bill is not yet publicly available and the date of publication has not been announced. However, the March 16 press release from the Council of Ministers mentions a wider jurisdiction on war crimes, the introduction of the crime of aggression and the extension of universal jurisdiction.

The noticeable absence is crimes against humanity, which keeps it impossible for Italian prosecutors to prosecute on that ground crimes connected to Ukraine and to migrants coming from Libya. “Even though we have laws on torture, murder and rape, these are not viewed in the systematic and widespread way that the introduction of an international code would have allowed,” regrets Meloni. The law they had drafted included apartheid, persecution and forced disappearence, she explains. That was not kept either.

The commission’s May 2022 final report says the reform would create an organic set of modernized laws. The qualification of “cultural genocide” and the possibility of prosecuting legal entities were notably part of the commission’s plans. These additions would have brought Italy up to date with some of the contemporary developments in international law.

What is left is the crime of aggression, in coherence with Italy’s 2022 ratification of the Kampala amendment to the ICC statute. The press release also announced a wider jurisdiction on war crimes. To date, war crimes in Italy are included in the military peace and criminal code, dating back to 1941, prior to the Geneva Convention, explains Meloni.

Concerning universal jurisdiction, the government says the new framework will allow prosecution of international crimes “wherever committed, if the perpetrator is permanently in the territory of the State”. The commission itself had made jurisdiction conditional on the suspect being present on Italian territory. However, by adding “permanently”, the Council of Ministers seems to be taking another step backwards.

“From a political point of view, that fact that a bill brought by three ministries of such weight, namely Justice, Defence and Foreign Affairs, was blocked by the Council of Ministers without notice is very serious,” says Meloni. “The legislative gap left is unjustifiable because the commission was highly qualified. I don't know when such a condition will ever happen again.”

International look

“You do see a lot of resistance at various levels within bureaucracies or within the military, many countries have had the same discussions at some point,” comments Philip Grant, executive director of TRIAL International.

Grant traces the history of universal jurisdiction back to an initial enthusiasm in the 1990s and early 2000s, then subsequent backlash and partial restriction of these laws’ scope. But gradually, after the beginning of the 21st century, with more states ratifying the Rome Statute and an increasing number of victims, witnesses and perpetrators arriving to Europe, dozens of cases went to trial. “I think there's a practice now that shows universal jurisdiction is set to be something durable and does not bring political persecutions into play. We don’t see abuses of universal jurisdiction anywhere,” says Grant.

Germany stands as an example of that. Since the country integrated international crimes into national law in 2002, German courts have conducted many universal jurisdiction trials. Two recent ones have been the case of an ISIS fighter convicted for genocide in 2021 and of a Syrian charged with crimes against humanity in 2022. But “updating the material law is just the first step,” says Patrick Kroker, German lawyer for the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights’ work on Syria.

Then specialised prosecutors, functioning war crime units, and special ways of investigating are also needed. Germany has experienced a learning curve over the last two decades that Italy would need time to catch up with. Kroker stresses that structural investigations need time: “You start very early and you go very broad in your investigation to understand the structure of the crimes of the group of perpetrators.” In the case of Syria, Kroker explains that all the trials were only made possible by structural investigations started back in 2011.

“Fighting impunity for international crimes should be considered a shared burden of the international community,” says Grant. “It should not be left to a few countries.” Denmark, the other European country lagging behind on international crimes, is planning to change its legislation to better support investigations on Ukraine, he notes. And Italy is not totally left behind, as it has historically made efforts to prosecute and judge, for example, American CIA agents, South Americans in trials related to the Operation Condor, and even human trafficking in Libya. “It should be in line with those endeavours. It really kind of puzzles me to understand why Italy is taking so long,” says Grant.