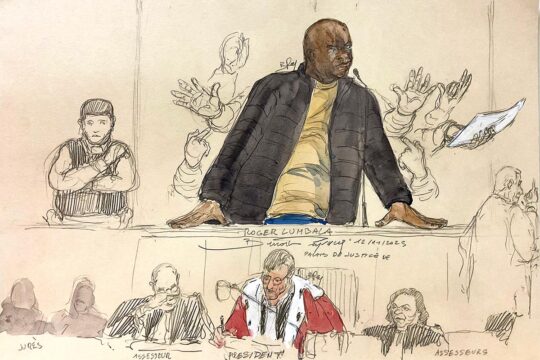

"Excuse me, but is this the trial of the accused or of the witness?" said Emmanuel Altit, the defence lawyer, on 22 May. In fact, there was little mention of the accused, Philippe Hategekimana, at the end of the afternoon at the Paris criminal court. The former Rwandan gendarme has been on trial since May 10 for acts of genocide and crimes against humanity committed in the Nyanza region in southern Rwanda in 1994. But this Monday, the witness present through video conference is a personality well known to international justice. Hormisdas Nsengimana, 68, a Catholic priest and former director of Christ the King College in Nyanza, was accused of genocide and crimes against humanity before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). He was eventually acquitted in 2009, the trial chamber finding that the evidence presented by the prosecution was not sufficiently credible to prove beyond reasonable doubt the priest's guilt. This was a victory for his defence, which was then conducted before the UN tribunal by Altit, who is now Hategekimana's lawyer. But it was a scandal in the eyes of the Rwandan government and the victims' organisation Ibuka, also a civil party in the gendarme's trial.

Now living in Italy, Nsengimana has known the accused almost all his life. As he recalled in his opening statement, he and Hategekimana were born in neighbouring villages in the south of the country. "I had the opportunity to be in contact with him at the time," said the priest in his nasal voice. The two men met again in Europe a few years ago, when the priest was visiting a colleague in Brittany. "He put me up for one night before I went back on my way," Nsengimana explained. "So you stayed in touch?" the president asked. "No, not really, it was my colleague who knew him. To say that I stayed in contact with him is excessive. We spoke on the phone from time to time.”

"I can't say who was an extremist or not”

Regarding the crimes that Hategekimana is accused of having committed in the Nyanza region in April 1994, the priest said: "I have never heard that the chief warrant officer was involved in the massacres. As I know him, he was a very balanced man and he spoke with people from both communities. He was not biased towards one ethnic group or another.”

Nsengimana said he had no real contact with Hategekimana during the genocide. A term he would never use, speaking of a "very tense situation". "I didn't go out much because the situation was very tense. But I had to go and buy food. And of course I would ask about the situation.” When asked by a witness how he could be so sure that Hategekimana was mixing with both ethnic groups and remained "moderate," as the witness put it, he simply replied: "I told you, we grew up together.” Faced with questions from the victims lawyers, he was however at pains to give the names of Tutsis that the accused had frequented, mentioning only one Hutu family that had hidden Tutsis and that Hategekimana, according to what he heard, had helped.

Hategekimana is not the only one whom the priest considered to be 'moderate'. Of a worker at Christ the King College suspected by the ICTR of having been involved in several murders, he also said he thought he was "moderate", although he qualified: "My contact with him was limited.”

“Did you know people who were extremists?" presiding judge Jean-Marc Lavergne finally asked.

“Frankly, I cannot judge anyone. Apart from the chief warrant officer, whom I knew to be moderate, I cannot say who was an extremist or not," the witness replied.

In general, the priest said he knew little about what happened in the Nyanza region in April and May 1994, reiterating again and again that he "didn't go out much".

“Were there massacres in and around Nyanza?”

“Listen, I personally did not go out to see if there were massacres or not. But everyone knows that there were massacres, I heard about them.”

“Who was massacred?”

“Tutsis.”

“By whom?”

“You're taking me very, very far here. I didn't go out so I can't tell you by whom!”

"I have been accused of many things but they were only rumours”

When the president of the court asked him about possible massacres committed by gendarmes in the region, the witness evaded.

“During my trial, I heard about acts committed by gendarmes but not about massacres.”

“During your trial, were gendarmes implicated in the murders of people that you yourself were accused of having killed?”

“A gendarme who committed murders, we didn't talk about that, no," Nsengimana finally replied after a silence. “But we did talk about gendarmes who arrested people.”

The judge read an extract from the ICTR acquittal decision concerning him - in which it is recalled that his defence argued that the murder of an abbot in the parish church of Nyanza, of which Nsengimana was accused, had in fact been committed by a gendarme or a soldier. Then, faced with the witness's poor memory, he read other extracts in which the involvement of gendarmes in murders was mentioned. Each time, the priest justified himself - "I did not reread the judgment before coming to testify" - and showed his perplexity: "Yes, it reminds me something but I have the impression that there have been additions [to the text].”

For nearly two hours, the accusations against the priest hovered over the hearing, feeding the questions of the president and later the civil parties. Murders of Tutsi clerics, of a pupil who came to seek refuge in his school, leading bloodthirsty armed groups... “I was accused of many things, but the prosecutor could not produce any reliable witness," recalled Nsengimana, "they were only rumours.”

On the defence bench, Altit ended up being irritated that the witness he had called was being tried again. The president replied that he felt it was necessary to assess his credibility. "In this case, I reserve the right to tell the witness not to answer these questions because it is self-incrimination," the lawyer said. “Self-incrimination of what?" the prosecutor Céline Viguier retorted. “He was acquitted!” And the president asked that these untimely interruptions stopped.

"Was there genocide in Rwanda?

When it was the turn of the civil parties, the lawyers tried in turn to find out how Hormisdas Nsengimana could have travelled to Nyanza and as far as Butare to meet his bishop (a Tutsi, according to the priest, who advised him to "stay quiet in his school") without seeing with his own eyes the massacres in progress. "No, I didn't see any victims near the roadblocks, fortunately," replied Nsengimana. But Richard Gisagara, one of the lawyers for the civil parties, asked the same question he had asked the week before to another acquitted ICTR witness, General Augustin Ndindiliyimana: "Was there genocide in Rwanda?

To this, the former chief of staff of the Rwandan gendarmerie, acquitted on appeal in 2014, had replied on May 16: "I cannot deny the genocide since it was recognised by the ICTR. As for me, I think that people died. Hutus died, Tutsis died.” Ndindiliyimana had also insisted on the need to set up roadblocks back in 1994 in order to flush out "infiltrators" of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the rebellion that took power in July 1994, ending the genocide. The prosecutor reminded him of the many civilians killed at these checkpoints, and the general replied: "We should have given clearer instructions, but that was not the case.”

On May 22, facing Nsengimana, Mr Gisagara took the offensive again: "You speak of a 'troubled', 'very tense' period; do you recognise today that it was a genocide?” "The question has been decided by the ICTR," said the priest. And when another lawyer for the civil parties repeated the question, the clergyman got angry. "I repeat, the issue has been decided by the ICTR. We're not going back to that!" he exclaimed.

Philippe Hategekimana, sunken in his seat in the dock, then seemed to have been forgotten.