On May 12, 2023, the Court of Cassation made up for its faux-pas of November 24, 2021, when it ruled that crimes against humanity committed by Bashar al-Assad's regime could not be punished in France because they were not punishable under Syrian law.

Sensitive to the outcry provoked by this decision, which surprisingly saw the Ministries of Justice and Foreign Affairs join NGOs and the public prosecutor's office join opposition to the ruling led by the International Federation for Human Rights, a plenary session of the Court of Cassation overturned the court’s own November 2021 decision. It finally gives the green light to the resumption of proceedings initiated by the national anti-terrorist prosecutor's office against Syrians living in France and suspected of having taken part in the regime's crimes.

Legal stop-go for over a century

To appreciate the subtleties of this legal stop-go affecting the role of national courts in judging international crimes, it is useful to take a broad look at the tentative development of international criminal law over more than a century.

Traditionally, criminal law has been regarded as territorial in application. Each State legislates on what it intends to punish, and prosecutes, in principle, offences committed on its own territory. It is true that, from the end of the 19th century onwards, "international crimes" were defined by international conventions, dealing essentially with what could no longer be tolerated in the conduct of war, and leading to the gradual development of international humanitarian law. But without international courts to apply them, repression remained essentially a dead letter. For example, the Treaty of Versailles of 1918 provided for the indictment of German Emperor Wilhelm II before an international criminal court, but this court never saw the light of day.

The creation of international tribunals has therefore long been the ideal pursued by campaigners for a peaceful world governed by the rule of law. After the Second World War, the creation of the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals was supposed to be followed by that of an international criminal court, provided for in the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention of Genocide. But the Cold War was to have its way, and, as in 1918, this project remained a dead letter.

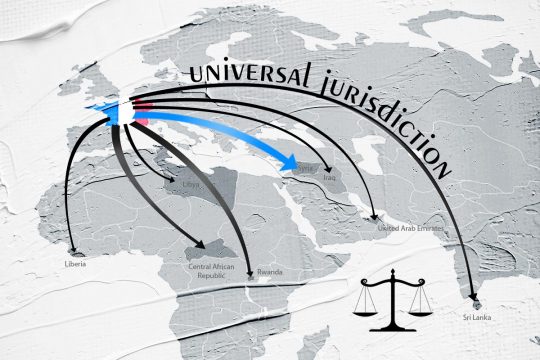

The old dream of universal justice to enforce a global legal order guaranteeing peace and human rights thus faded in the post-war years, until it was reborn in a much more timid form in the years following the fall of the Berlin Wall, which saw the successive births of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 1993, for Rwanda in 1994 and, finally, the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 1998.

“Complementary" justice

It was more timid because, right from their conception, these three tribunals were seen not as the expression of a global justice system with supremacy over States, but as part of a cooperation mechanism between this nascent international justice system and national justice systems.

Created by the UN Security Council, the first two international criminal tribunals (the "ICTs") were intended to try only those most responsible for the wars in the former Yugoslavia and the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda. States were expected to prosecute lesser perpetrators themselves. For this reason, two laws passed in 1995 and 1996 gave French courts jurisdiction to try the perpetrators of crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda who were found on French soil. Their mere presence on French soil makes French justice competent to prosecute them. It is on this basis that several perpetrators of the Tutsi genocide have already been tried in France.

Created by treaty, the ICC is also intended to judge only the most serious international crimes, and the preamble to its Statute emphasizes that "it is the duty of every State to submit to its criminal jurisdiction the perpetrators of international crimes". Its Statute goes even further than those of the two International Criminal Tribunals, since it gives priority to those States with primary responsibility for prosecuting international crimes, with the ICC itself intervening only when no state does so. In other words, the ICC is only intended to complement the national courts, which have primary responsibility.

So when in 2006 French Justice Minister Pascal Clément tabled a bill "adapting criminal law to the institution of the International Criminal Court", observers were eager to read how France intended to take its place in this new international legal order based on cooperation between international and national courts.

The answer was simple: France would do nothing.

The bill prepared by the Ministry of Justice did indeed include international crimes in the French penal code, but it did not contain a single line authorizing French courts to try such cases, unless they involved French nationals or took place in France.

Universal jurisdiction under lock and key

For two years, the French Coalition for the ICC, bringing together some 40 NGOs, trade unions and Bar associations, tried to raise awareness among political parties and members of parliament so that France would play an active role in this nascent international judicial cooperation system, designed to ensure that the most serious crimes do not go unpunished.

In the spring of 2008 when this bill, initially totally silent on opening up French courts to universal jurisdiction, was finally placed on the agenda, all parliamentary groups (except the UMP, then in power) voted in favour of amendments introducing universal jurisdiction, tabled in particular by senators Robert Badinter (Socialist) and Pierre Fauchon (centrist).

Sensing that the Senate was on the verge of tipping, Justice Minister at the time Rachida Dati and the UMP rapporteur Patrice Gélard calculated that they could accept these amendments while at the same time trying to empty them of their substance. Four draconian conditions, denounced by NGOs, were thus laid down for perpetrators of international crimes to be prosecuted in France:

- that they have made France their "habitual residence". Despite Badinter's efforts to have this condition of habitual residence replaced by a condition of mere presence in France, such as already existed for the crime of torture or within the framework of cooperation with the ICTY and ICTR, the majority followed the rapporteur and the government;

- prosecutions should be initiated by the public prosecutor and not the victims;

- that the acts be punishable under the law of the State where they were committed. This is the principle of double incrimination at the heart of the case that has just been arbitrated by the Court of Cassation;

- finally, that the ICC declines jurisdiction. This condition gives priority to the ICC whereas the ICC Statute, on the contrary, gives priority to national courts.

The bill was passed by the Senate in 2008. It was adopted by the National Assembly (lower house) in 2010 with the same terms, and the new article [689-11] entered the French penal code.

Continuity of governance

Numerous initiatives have been taken since 2010 in an attempt to reverse this vote and amend the law. Socialist François Hollande pledged to do so during his 2012 election campaign, but this promise was forgotten, despite a bill proposed by Socialist Senator Jean-Pierre Sueur, which was unanimously adopted by the Senate but never placed on the agenda of the National Assembly. Continuity of governance goes beyond majorities.

In 2019, however, the vote on a justice law removed the fourth constraint (replaced by a simple check that the person about to be prosecuted is not already being prosecuted by an international tribunal or another country), as well as the double criminality condition, but only for genocide. It was therefore maintained for crimes against humanity.

This condition was seized on by the lawyer of a Syrian army reservist, arrested in France on suspicion of having taken part in the repression of demonstrations and arrest of civilians. As NGOs had feared, the Court of Cassation ruled on November 24, 2021 that the charges against him should be dropped, as Syrian law does not punish crimes against humanity.

Court of Cassation relaxes two constraints

A year and a half later, the Court of Cassation reversed its decision, finally opting for a flexible interpretation of double criminality.

In essence, it held that crimes against humanity are not punishable as such in Syria, but that acts which are qualified as crimes against humanity under French law because they were committed in execution of a concerted plan are also punishable under Syrian law as ordinary offences (murder, rape, torture): "It should therefore be noted that the condition of double criminality (...) does not imply that the criminal characterization of the acts is identical in the two legislations, but only requires that they be criminalized by both".

In a second case, also decided on May 12, the Court of Cassation ruled on the condition of habitual residence. The suspect, also Syrian, sought to have the prosecution quashed on grounds that he was actually living in Turkey with his family, had only come to France to study for a time, and was therefore not ordinarily resident there.

The Court of Cassation opted for a flexible interpretation of this condition, stressing that "habitual" residence is not necessarily permanent, nor even "principal" residence. It even accepted that it is possible to have a habitual residence in France while living mainly abroad, the aim of this criterion being merely to ensure a "sufficient" connection to France, which would be lacking in the case of a mere presence for a few hours on French territory.

These two rulings were therefore greeted with relief by those in favour of a more aggressive assertion of France's universal jurisdiction.

Obstacles now removed?

If we add to this the removal of the fourth constraint (relating to the ICC) by the 2019 law, should we consider that the obstacles erected in the way of universal jurisdiction have now been removed?

No, because several anomalies remain. Even if neutralized by the court’s recent interpretation, the double criminality condition remains questionable in principle. International crimes are said to be international precisely because they undermine universal values. To make their prosecution subject to the condition that they can be prosecuted by the State that committed them or allowed them to be committed is cynical relativism denying recognition of the universality of values it is intended to protect.

Since the Court of Cassation has now rendered this condition practically useless, why maintain it in law when it runs head-on against our international commitments?

This is why, as soon as the May 12 rulings had been handed down, several MPs from the Renaissance presidential majority group reintroduced on May 23 a bill designed purely and simply to remove what remains of the constraints put in place 15 years ago.

As for the habitual residence requirement, while the traditional criterion for universal jurisdiction is mere presence, rationally it remains unjustified, even if relaxed by the May 12, 2023 case law. Should we accept that, for the same crime, a Serb or a Rwandan should be liable to prosecution as soon as he sets foot in France [as a result of the 1995 and 1996 laws cited above], while we should let a Syrian or a Liberian come and go with impunity as long as they don't settle down for longer?

Finally, the impossibility for victims to initiate prosecutions due to the monopoly of the public prosecutor's office, whereas victims of the slightest offence normally have this right, undoubtedly responds to the concern to reconcile justice and diplomacy by relying on the public prosecutor's office to initiate prosecutions only with discernment. But it undermines another human right: the right of victims to have access to a judge.

Supremacy of Realpolitik over law

This last barrier masks a discreet struggle by French diplomats to ensure the supremacy of Realpolitik over the law, even when it comes to massacres and genocides: through the intermediary of the public prosecutor's office, the State intends to reserve a margin of discretion over the appropriateness of prosecutions, and resists with all its might the idea that, when it comes to international crimes, there is an obligation to prosecute the perpetrators.

This French activism was again in evidence at the end of May in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, where a conference was held to negotiate a draft treaty on international mutual legal assistance, known as the MLA (Mutual Legal Assistance) or, more officially, the "Convention on International Cooperation in the Investigation and Prosecution of the Crime of Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, War Crimes and Other International Crimes".

Even if France does not admit it, it is often considered that the obligation to ensure prosecution of perpetrators of international crimes is an unwritten obligation, based on international custom. It is based on the principle aut dedere, aut judicare -- either extradite, or prosecute – or in other words, either acquire universal jurisdiction to prosecute suspects oneself, or hand them over to a State or international tribunal to do so.

The MLA Convention - which States will be asked to sign in The Hague in 2024 - now formally lays down this obligation. French and British diplomats have tried in vain to have it amended and make prosecution optional. But the text adopted on May 26 stipulates that States are obliged to exercise jurisdiction over the perpetrator of an international crime whenever he or she is present on their territory. France and the UK have only obtained the right to formulate a reservation on this point, for a renewable period of three years.

Has the countdown to the end of the French exception begun? The ball is now in Parliament's court with the Renaissance group's proposed law which, some 20 years late, would bring French law into line with this principle. But will it be put on the agenda this time?

Simon Foreman is a member of the Paris Bar. As a civil parties' lawyer, he has taken part in several universal jurisdiction trials involving Rwandan and Liberian defendants. Former president of the French Coalition for the International Criminal Court (2006-2016), he is a member of the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights.