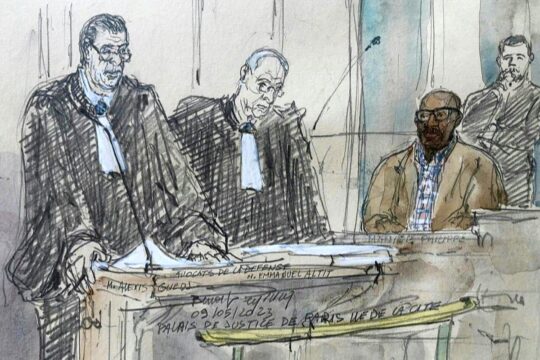

Marie Ingabire was seven years old when she saw her mother cut into pieces by Interahamwe militiamen at the foot of Bwezamenyo hill. Anne-Marie Mutuyimana was 10 at the time of the genocide, and Eugène Habakubaho was 11. A dozen people who were under 15 in 1994 have testified and acted as civil parties at Philippe Hategekimana's trial. The former Rwandan gendarme – who obtained French citizenship in 2005 - has been on trial for genocide and crimes against humanity since May 10 in Paris. These child victims, now aged between 30 and 40, lost most of their relatives at the roadblocks that lined the Nyanza region in southern Rwanda, in the massacres in the Nyamure and Nyabubare hills, and at the Isar Songa agricultural science institute. Hategekimana is accused of having participated in, or even led, all these attacks between April 23 and early May 1994 - a period during which he claims to have been on his way to Kigali, where he had been transferred.

Some of these civil parties are the sole survivors of their families. And their testimonies - often interrupted by the pain of remembering - are tales of survival in widespread chaos, from a child's point of view. They are just as precise about landscapes and certain details that changed their lives as they are vague on faces and dates.

On June 16, testifying by videoconference, Marie Ingabire recounts her mother's last words: "If you must kill me, kill me, but please spare my child.” She remembers the elderly blind couple who told her to hide in the field behind their house, and the sorghum stalks she was told not to move.

Anne-Marie Mutuyimana was ten in 1994. On June 12 she told how she remembers hearing her father and uncle discussing, at the start of the genocide, the best hiding places for a child, such as certain squash trees whose thick foliage would be enough to camouflage someone small. This saved her life a few days later, when she was alone and being chased by an Interahamwe armed with a machete, and she scrambled under the branches of one of these trees. Earlier, hiding below the Nyamure hill, she remembers hearing a tremendous noise, "as if the hill was falling". On this hill, where thousands of Tutsis had taken refuge, the Nyanza gendarmes - including Hategekimana - allegedly fired a mortar, according to the indictment

The challenge of identification

This story echoes that of Florence Nyirabarikumwe, aged nine that spring, who was at the top of the hill. "One day, in the early afternoon, I heard my mother say that it was the end of us, because this time the gendarmes were coming,” she told the court. “Then I heard the sound of bullets. I could hear things exploding, and I saw a piece of human flesh fall next to me."

Quite often their stories drag on, as these witnesses describe in detail their chaotic journeys during those murderous days. On May 30, Eugénie Murebwariye spent nearly three hours recounting her memories, including the widespread anxiety in her family after the presidential plane was shot down on April 6, 1994; the death of the Nyanza mayor; the flight of her father and brothers to Nyabubare hill; and the refuge she eventually found in an orphanage. On two occasions, court president Jean-Marc Lavergne expressed concern that she was straying from the facts of the case. "Madame, I'm going to have to interrupt your testimony unless you have something essential to tell us about the facts before us." But she continued her story to the end. At the end of the hearing, the judge told the plaintiffs' lawyers that "it would be a good idea to warn [their] clients that there is a hearing schedule to respect" and that, however painful the memories recounted, the court could not take so much time to listen to them. "We do our best, Mr. Chairman," replied lawyer Richard Gisagara.

“The president would like our clients to concentrate on the facts in the indictment, but the victims can't divide up their testimonies, even less so those who were children at the time of the events," sighed his colleague Hector Bernardini. "For them, their story begins at the start of the genocide and everything follows on from it.”

The challenge of dates

As the hours and stories stretch on, we often found ourselves forgetting the main protagonist of this trial: the accused. The defence - led for most of these hearings by attorney Margarita Duque - frequently reminded witnesses at the start of their questions that they were "very young" at the time, and demanded details they were hard pressed to provide. When the lawyer asked them for dates, even approximate ones, they couldn't always answer. “I can't talk about dates and days," replied Gloriose Musengayre, who was 15 during the genocide. “I was young. I could see the day coming, the night coming, but I couldn't say what day it was."

Some, on the other hand, claim to be able to give a precise date. Eugène Habakubaho, 11 in the spring of 1994, recalls that the attack on Isar Songa, which he survived, took place on April 28. "How can you be sure it was April 28?" asked Judge Lavergne. "I can't forget that day," replied the witness simply. Yvette Umutoni Niyonteze, aged 10 at the time of the events, remembers perfectly that May 7, 1994, when militiamen led by two gendarmes came to search the house where she was hiding. Hidden in a false reed ceiling, she saw one of the gendarmes enter the room. She later learned from listening to the nearby militiamen that this man was the notorious "Biguma" she had been hearing about for days, who coordinated numerous attacks. "Biguma" is the nickname of the accused, Philippe Hategekimana. "If you saw him, could you describe him to us?" asked the judge. "I couldn't describe him perfectly since we weren't face to face and I could see him only through reeds."

She is one of the few witnesses in this trial - and one of two who was a child at the time - to say she saw Hategekimana at the precise moment of the events. Other "child witnesses" heard the name "Biguma". Eugénie Murebwariye, for example, said she heard the militiamen at the roadblocks describe this man as a leader, asking them to "work, work", which meant kill Tutsis in the language of the genocidaires.

Julienne Nyirakuru claimed to have seen him. She was nine years old when she found refuge at the top of Nyamure hill. Tutsis had gathered there to resist successive attacks by the Interahamwe, throwing stones collected by women and children. One day, after multiple attacks, as she ventured down the hill with a group of children, she saw a vehicle arrive with men in uniform. An Interahamwe spoke to one of them, calling him "Biguma". The latter allegedly exclaimed: "What are those Tutsi dogs doing here? Haven't you killed them yet?” The militiamen complained that they didn't have enough weapons, so the gendarmes opened the trunk of the vehicle and handed out machetes. Julienne climbed back to the top of the hill. "I told my aunt they were going to kill us all,” she recounted. “Moments later, the bullets started flying.” Her aunt was shot in the leg and finished off with a machete by an Interahamwe, and Julienne pretended to be dead beside her. Later, taking refuge on the hill of Karama, she again heard the name "Biguma" from an old man, who said this man had arrived to attack them, at the head of his gendarmes and numerous militiamen.

Duty to remember

When she appeared before the court as an expert witness on May 11, 2023, the academic Hélène Dumas spoke of the "inverted world" described by those who were children at the time of the genocide: the disappearance of childhood landmarks, the transformed relationship with adults, who were incapable of protecting them or were, on the contrary, the perpetrators of the violence they had experienced. During her research, she expressed surprise at what she describes as the "hypermnesia" of victims, especially children.

“Children really do have scenes frozen in their memory," adds Domitille Philipart, lawyer for several civil parties. “Their reference points are not the same as those of adults. The relationship with time, in particular, can be distorted. Certain moments of waiting may seem to last for hours, whereas during an escape through the bush, the hours may, on the contrary, become shorter. But some scenes are frozen in their smallest details." The shape of a squash tree, a body part, motionless sorghum stalks. “You have to bear in mind that these children are talking about places they knew by heart, places they walked a lot before the events," continues the lawyer. “They were rooted in the area, and therefore had a very strong memory of the place.” At the same time, some faces disappear in the morass of memories. During the investigation, neither Yvette Umutoni Niyonteze nor Julienne Nyirakuru recognized Philippe Hategekimana as the famous "Biguma" on the photographs they were shown.

But, like the others who had never met him, it may not be so much against him that they have come together as civil parties as for remembrance. “I think that what's at stake for these former children is that their words be taken into consideration," says Philipart. “During the investigation, some hearings didn't go very well, because the investigators considered that the victims were so young at the time of the events that they could surely confuse a lot of things. But some of these victims have very precise memories. So it's very important for them to come forward and testify at the hearing.” And, as the lawyer points out, they are sometimes the only survivors in their family, so "they also come to testify out of a duty to remember".