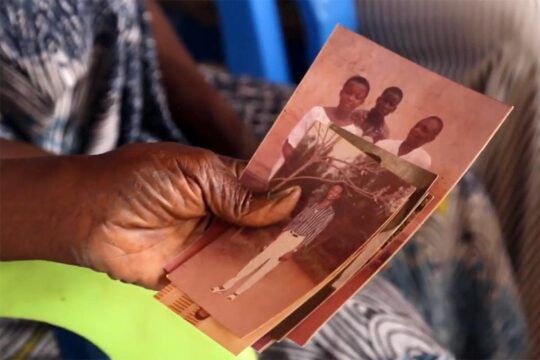

In a well-established weekly ritual, the "Saturday Mothers" meet in a small street in Beyoglu, in the centre of Istanbul, then gather in Galatasaray Square with their commemorative placards displaying portraits of disappeared relatives. There is an imposing police presence: riot police, barriers, water cannon trucks. Caught in a police noose, a handful of activists hastily attempt a press conference before dispersing – if they are not taken away in a police van. For 28 years and almost 1,000 weeks, with a few interruptions, the Saturday Mothers have been demanding justice for their loved ones, presumed victims of enforced disappearance after being arrested by the security forces. But to no avail.

These missing persons - 1,352 individuals, mostly men aged between 12 and 73, according to a note published in 2022 by the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) - were journalists, trade unionists, doctors, teachers, farmers and ordinary villagers from the predominantly Kurdish region of Turkey. Human rights activists suspect they were disappeared during illegal detentions and in unsolved murders. These practices were widespread at the height of the Turkish state's "dirty war" against the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party) insurrection in the south-east of the country in the 1980s and 1990s. This war continued with a relentless crackdown on the civilian population.

2011: Erdogan awakens families’ hopes

In 2011, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then Prime Minister, met these activists and raised the hopes of their families. Those calling for an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes believe that the investigations were botched in the name of the "fight against terrorism". But despite its desire to join the European Union, expressed once again on the sidelines of the recent NATO summit, Turkey has never ratified the International Convention against Enforced Disappearances, which came into force in 2010.

On 25 August 2018, for their 700th gathering, the activists were in turn accused by the state of collusion with "terrorist groups". Their rallies were brutally dispersed and banned for more than four years. But last February, the Turkish Constitutional Court ruled that the demonstrators’ rights had been violated. The Saturday Mothers immediately returned to Galatasaray Square. And on 26 May, 14 demonstrators were acquitted by the criminal court on charges of "illegal assembly".

Nevertheless, the government continues to prevent demonstrations. As recently as July 8, a lawyer representing the families was arrested as he was explaining to the security forces that their action was contrary to court rulings. "Impunity is the message being sent out," concludes Eren Keskin, a lawyer and long-standing human rights activist who, with her association IHD, has supported these rallies from the outset.

2016: the return of enforced disappearances

Keskin has seen these practices return. Enforced disappearances in Turkey are not just a thing of the past, she tells Justice Info. There has even been a sharp upsurge in cases since the failed coup of July 15, 2016, to which the authorities responded with a wave of mass arrests. And the prophecy of former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu has been borne out: in 2015, he expressed fears of a "resurgence of white Toros", the local version of the Renault 12, which once symbolised the death squads of Turkey's paramilitary forces and these unexplained disappearances. The vehicles have been modernised. Now there are fears of a "black Transporter".

In a May 2020 report entitled "Enforced Disappearances in Turkey, an Open Secret", the "Solidarity with Others" organisation documented at least 25 cases since 2016. "On numerous occasions, armed men identifying themselves as police officers have forced victims into a van, often a black Volkswagen Transporter with tinted windows," reports the Brussels-based NGO founded by exiled members of Fethullah Gülen's brotherhood, accused of conspiring against Turkey. "Some of them reappeared months later, after having been tortured, while others never returned home," the report states. This is the case of teacher Sunay Elmas, kidnapped in Ankara in January 2016. And Ayhan Oran, an agent of the Turkish intelligence services, who disappeared in November of the same year. Most of them were former civil servants close to Gülen, "purged" by the regime. And those who eventually resurface sometimes find themselves accused of crimes they confessed to during their secret detention.

Faruk Gergerlioglu, a doctor and staunch defender of human rights, is one of the few MPs to be urging that light be shed on recent cases. Despite relentless political pressure and the threat of a prison sentence, where he already spent three months in 2021, he was re-elected last May on the ticket of the YSP (Green Left Party), the pro-Kurdish left, and he continues to question Ankara. "We have come across many cases of abductions and enforced disappearances in Turkey over the past seven years after the state of emergency was declared [following the failed coup in July 2016],” he explained in an interview at the beginning of July. “Thousands of cases in the 1990s have not been resolved, and the same incidents began to recur during the state of emergency [maintained until July 2018]. People were clandestinely abducted in other countries by the MIT (Turkish intelligence services) and forcibly brought to Turkey."

“Citizens of this country have been abducted and tortured while being held illegally in the same place for months on end," continues Gergerlioglu. “How do we know this? Some of these people have spoken about it in court after their release, they have told their relatives and their lawyers, in letters they sent from prison, so we know that these cases are violations of rights. We have identified 35 examples. It is clear that this is a common and indisputable practice."

Erdogan's "black box" promoted head of diplomacy

The MIT is suspected of being involved in the majority of disappearance cases. Kidnappings abroad have sometimes been openly claimed by the State, but when it comes to cases in Turkey, there is an ominous silence. When Gergerlioglu questioned MIT officials in parliament, he got no answer. “The questions went unanswered," continues the Turkish MP, "but one of the MIT agents was himself kidnapped and tortured after being dismissed from his post. He has not been seen, dead or alive, for six years. The Constitutional Court ruled that the investigation into his abduction had been incomplete, and ordered that the family receive financial compensation of 90,000 Turkish pounds (around €3,150). But that's the end of the investigation and no legal action has been taken against MIT."

The MIT appears to be untouchable. At the heart of the government, the Turkish intelligence services are directly under the authority of the Presidency. For a long time, they were headed by Hakan Fidan, nicknamed Erdogan's "black box". But in June he was appointed foreign minister. He was replaced at the head of MIT by Ibrahim Kalin, who until then had been the President's spokesman.

"Prosecutors said they did not want to interfere in the work of the MIT. The investigations were interrupted, the recordings from the city's surveillance cameras were not properly studied, we saw all the investigations drag on," notes the veteran human rights activist, noting that, as for torture cases, impunity prevails.

* Guillaume Perrier is a journalist at Le Point, former correspondent in Turkey, and author of "Les loups aiment la brume" (Grasset, 2022), an investigation into Turkey's clandestine operations in Europe.