On the 29th of June 2023, the United Nations voted in favor of establishing an independent institution on missing persons in Syria. Its goal is to “clarify the fate and whereabouts of all missing persons in the Syrian Arab Republic and to provide adequate support to victims, survivors and the families of those missing.” The UN resolution emphasizes the “full and meaningful participation and representation of victims, survivors and the families”, something that has been at the core of the Syrian diaspora’s demands.

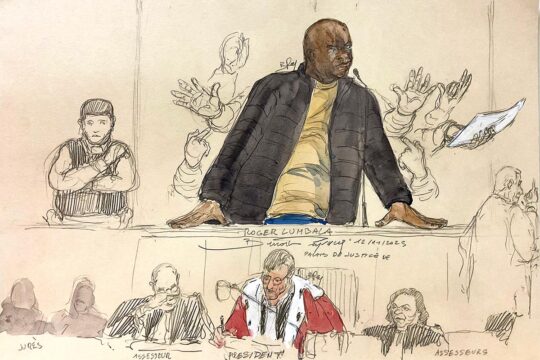

While Syria and a few other countries like China, Iran and Russia voted against the resolution, and all the Arab countries except Qatar and Kuweit abstained, it comes as no surprise that Germany was one of the 83 countries in favor. In the past years, Germany has presented itself at the forefront of seeking justice for Syrians. As early as 2011, the general prosecutor’s office opened several structural investigations into atrocity crimes in Syria and has been gathering evidence ever since. Based on the principle of universal jurisdiction, the German judiciary has opened several trials against the Assad-regime and its henchmen: In the German city of Koblenz, the worldwide first trial dealing with state-torture in Syria concluded in 2022 with the court convicting two former secret service officers for crimes against humanity. This April, an Assad-militiaman was sentenced to life in prison for war crimes after another trial in Berlin. Another member of an Assad-militia was arrested at the beginning of August 2023. And in Frankfurt, a Syrian doctor has been indicted with crimes against humanity for torturing prisoners in Damascus.

In the light of all these justice efforts and Germany’s vote in late June, it is hard to believe that Germany itself does not criminalize enforced disappearances in its national criminal code. As a state party to the UN convention against enforced disappearances since 2009, it is obliged to do so, but has been refusing to change the law for more than ten years. And that is not all: Germany also has severe shortcomings regarding the crime of enforced disappearance in its code of crimes against international law. These make it almost impossible to prove enforced disappearances, thereby minimizing the chance of prosecutors investigating and indicting such crimes. There have been demands to change both the German national and international law on enforced disappearances for years. Now a legal reform is in the making, and the crime of enforced disappearance might finally get the attention its victims demand.

Enforced disappearance, a crime on its own

In March, Germany was reviewed by the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances. It had been ten years since the last review when the Committee had ordered Germany to implement enforced disappearances into its national law, with no effect. During the review, the German representatives argued that existing criminal offences were sufficient to investigate and punish cases of enforced disappearances, citing for example offences against personal freedom, bodily harm and homicide, obstruction of justice, denial of justice and failure to render assistance. For critics like the German Institute for Human Rights (GIHR) this is not enough: “The enforced disappearance of a person is not a combination of different offences, but a single and multidimensional crime”, it stated in a submission to the committee. “Its content can only be properly covered by an autonomous offence of enforced disappearance.”

According to the UN working group on disappearances, an enforced disappearance is not only “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State” but must be followed by the “refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person.” For the GIHR this twofold definition is crucial, because it ”covers two forms of enforced disappearance - the deprivation of liberty of a person with subsequent concealment of his or her whereabouts and the concealment of the whereabouts of a person previously deprived of his or her liberty.”

What sounds like one and the same in reverse, is actually an important factor for understanding the unique offence of enforced disappearance. Regarding the perpetrator this means: not only the person who abducts and detains the victim against their will is committing a serious crime, but also the state institution or officer that fails to provide the family or other inquirers with information. This interpretation of enforced disappearances also places a lot of weight on the fact that not only the disappeared person becomes the victim of a crime, but their loved ones, as well. They have to live with excruciating uncertainty, some of them forever.

Germany’s credibility at stake

For Silke Voß-Kyeck, a researcher at the GIHR, the need to implement enforced disappearance into German law is without question. “By ratifying the convention, Germany has committed itself to creating a legal basis for enforced disappearance in national law”, she tells Justice Info on the phone. Voß-Kyeck also sees a problem with Germany’s credibility: “Iraq has been working on a law against enforced disappearances for years. Germany is supporting them with money and legal know-how. Imagine an Iraqi parliamentarian’s reaction when they find out that Germany has no such law itself. Germany cannot push for legislation in other countries while interpreting them at will in their own criminal code.” In addition, the right to the truth is an important element of the convention against enforced disappearance, says Voß-Kyeck. “And part of the truth is calling a crime what it really is. Anything else would make a mockery of the victims.”

During Germany’s review at the Committee against Enforced Disappearances, a member of the German delegation claimed that enforced disappearances were not something that happened in Germany anymore. Voß-Kyeck disagrees, citing the case of a Vietnamese citizen who was abducted by the Vietnamese secret service in Berlin in 2017 and reappeared days later in Vietnam. The driver of the car that took him from Berlin to Bratislava could not be charged with complicity in an enforced disappearance, because that crime does not exist in German law. Instead, he got a relatively low sentence for aiding a deprivation of liberty among other offences.

Voß-Kyeck also mentions the case of German citizen Murat Kurnaz who was detained in Guantanamo without charges from 2002 to 2006: “Before his family ever found out where he was, the German authorities knew he was in Guantanamo.” They might not have abducted him, but by knowing and concealing his whereabouts they would have been accomplices to an enforced disappearance, she explains. And even if there were no cases at all, criminalizing this offence according to the convention is important, insists Voß-Kyeck: “Of all human rights conventions, this is the one with the strongest pre-emptive effect. It is written in a way that is meant to prevent the enforced disappearance of individuals in the first place.” In 2014, the Federal Commissioner for Human Rights at the time, Almut Wittling Vogel, confirmed the significance of this law for Germany: “We have learnt from our past how quickly lawless regimes can take over a society, and how important it therefore is to install structural legal safeguards against all possible kinds of human rights violations.”

Rampant but impossible to prove

Enforced disappearances have been among the most brutal crimes of regimes in Argentina, Iraq, Mexico and many other countries for years. Recently, the conflict in Syria where more than 100.000 remain disappeared and the war in Ukraine where Russia allegedly abducted children, have drawn more attention to this complex offence. While the German ministry of justice is preparing a judicial reform those lobbying for a specific legislation on enforced disappearances have managed to put their demands on the agenda. This does not only concern implementing the crime of enforced disappearance into national law, but also to change the code of crimes against international law (CCIL). The CCIL is the legal code that implements the provisions of the Rome Statute – the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court – into German law. It defines and penalizes the core crimes against international law – genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression – and allows Germany to prosecute these under the principle of universal jurisdiction, even when they are committed somewhere else with no direct link to Germany.

The CCIL was the legal basis for the Syria trials in Koblenz, Berlin and Frankfurt, but it also proved insufficient to prosecute the Assad regime’s crimes fully. “In Koblenz, it became clear that some things do not work in practice as they were intended by lawmakers and civil society”, says Voß-Kyeck. And one of the main concerns was the crime of enforced disappearances. Unlike in the national criminal code, enforced disappearance is a crime in the CCIL. But Germany’s definition of enforced disappearances is much narrower than that of the Rome Statute and the Convention against Enforced Disappearances: it requires proof that inquiries about the missing person were made with the authorities. Anyone who knows the reality in Syria – and other countries where enforced disappearances are rampant – understands that this looks like an impossible request. Asking about a missing person is not only futile, but also dangerous for the inquirer who would often end up in detention themselves or risk putting themselves on the radar of the security services.

Hopes for trials ahead

The consequences of this legal detail became clear in Koblenz, where more than 100 days of trial revolved around the torture and killing of Syrian women, men and children in the secret service’s detention centers. Most of them had been victims of enforced disappearances, most of their families knew nothing about their fate and whereabouts. Every Syrian witness or plaintiff – even the defendants – had several cases of disappeared family members and friends. And yet, the crime of enforced disappearance was not indicted despite the efforts of civil society groups, the plaintiffs and their lawyers. There would not have been enough evidence to prove that inquiries about the missing persons had been made.

For future trials at least, the situation will improve regarding enforced disappearances in both national and international law, according to Voß-Kyeck. “The ministry of justice has confirmed: they have started working on reforming both”, she says, although she cannot say how long that might take. Some other issues that were criticized in Koblenz and the other Syria trials are expected to be improved as well: the crime of sexual slavery is to be included in the CCIL, plaintiffs are to receive psychosocial support throughout the trial, translators are to be present to make trials accessible for non-German media representatives, and trials are to be audio-visually recorded for the use of historians and other academic researchers. The German judiciary, it seems, is preparing itself for more trials under the principle of universal jurisdiction – whether on enforced disappearances or other crimes against international law.