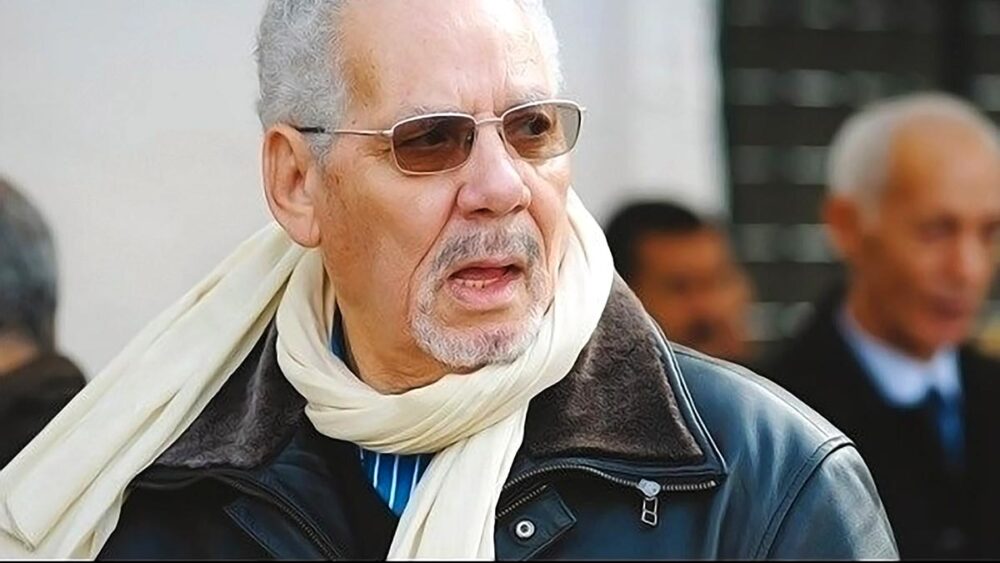

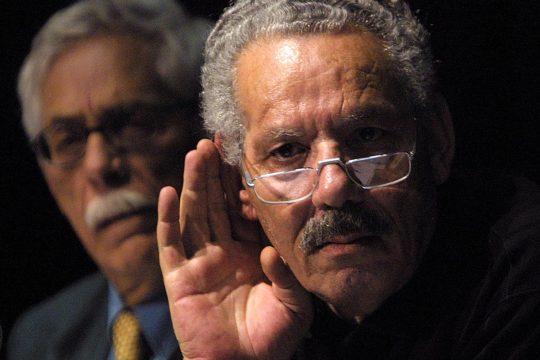

Both cases have been on the desks of Swiss judicial authorities for a decade or more. In mid-August, Switzerland unveiled an international arrest warrant for Rifaat al-Assad, uncle of the current Syrian president, for alleged crimes against humanity committed in 1982. On August 28 came an indictment against former Algerian defense minister Khaled Nezzar for war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed in his country’s civil war of the 1990s.

Geneva-based NGO TRIAL International, which brought the complaints that launched these cases, hailed both announcements. It called on Swiss authorities to swiftly indict Assad and bring him to trial. It says that if Nezzar is brought to trial in Switzerland, he “will be the highest-ranking military official ever tried for crimes based on the principle of universal jurisdiction” that allows some domestic systems to prosecute international crimes committed outside the country by non-citizens.

TRIAL International stresses that time is running out. In the case of Assad, it says “it is regrettable that we had to wait until his return to Syria before demanding he appear before Swiss courts”. Assad had previously been in France. In the case of Nezzar, TRIAL International’s legal advisor Benoit Meystre notes that “the defendant’s health has deteriorated over the almost twelve years of proceedings” and that bringing him to trial is “the only – but also the very last – opportunity to deliver justice for the victims of the Algerian civil war”, owing to an amnesty law in Algeria.

According to the NGO, Nezzar is reportedly dying in Algeria. He is now 85, whilst Rifaat al-Assad is 86.

“Algeria is absolutely furious”

Meystre admits that the chances of either man being brought to trial in Switzerland are “low”. “They are both old and if they pass away, the case will be closed,” he told Justice Info. “Both of them are currently being protected by their respective countries. It is difficult to foresee any possibilities that Syria would accept to extradite Rifaat al-Assad, and it’s the same for Nezzar. Algeria will most probably refuse to force him to come to Switzerland to be heard or tried. And it’s pretty clear they won’t come of their own free will, because there is too much at stake.”

Marco Sassoli, professor of international law at the University of Geneva, also points out that in the case of Nezzar “Algeria is absolutely furious, because it undermines the narrative of the current regime that they saved Algeria from the Islamist threat.”

Meystre says trials in absentia are possible. “We are hoping for a trial in any case,” he continues. “The first objective is that they be here to answer personally to the charges brought against them, but a trial in absentia would be an alternative, as it would still have some meaning for the victims,” he said.

Detained only briefly

Nezzar was arrested in Geneva in October 2011, following criminal complaints from TRIAL International and victims of torture during Algeria’s “Black Decade”. Following 48 hours of questioning by the federal Office of the Attorney General, he was released on condition that he attend subsequent hearings. He came to Switzerland for a final hearing in February 2022. “However, at the end of his final hearing, Mr. Nezzar was not detained,” TRIAL International noted at the time. “This is a cause of concern for the organisation, as the risk of flight, collusion and pressure on witnesses and victims remains important.”

The Assad case dates back almost as long. “The case started in 2013 and Rifaat al-Assad was not heard at the time,” explains Meystre. “He came back in 2015, was heard briefly, and then he basically fled for ever. The arrest warrant aims at forcing him to be brought to Switzerland to be heard.” There is not yet any indictment.

Assad fled Switzerland to France, where a court sentenced him in 2020 to four years in jail for money-laundering and embezzlement of public funds in Syria. This was confirmed on appeal in 2021, but he managed to escape back to Syria in October that year.

Lack of will and political interference

Switzerland’s Office of the Attorney General has also taken years over other universal jurisdiction cases. Former Liberian warlord Alieu Kosiah spent nearly seven years in pre-trial detention before being convicted and sentenced to 20 years in jail for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Gambian ex-interior minister Ousman Sonko has been remanded in custody since January 2017 but was not indicted until April this year. He is to be tried for crimes against humanity, but no date has yet been set.

Sassoli says there were several factors for the delays, including difficulties to obtain the necessary evidence, lack of will and allegedly political interference. “Algeria put a lot of pressure on Switzerland. According to the UN Special Rapporteurs on torture and on the independence of judges, the Swiss authorities allegedly tried to influence the prosecutor. The prosecutor finally – and this was not totally unreasonable – came to the conclusion after years that this was not an armed conflict” and tried to dismiss the war crimes case. But victims appealed to the Federal Criminal Court, which reversed the decision and ordered the prosecutor’s office to reopen its investigations. Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis denied allegations of political interference in the case.

Meystre believes that the Office of the Attorney General suffers from lack of resources, and the investigation is even more difficult because they cannot rely on Syria or Algeria’s cooperation on these cases, he says.

Blättler, a more active prosecutor

Sassoli said that previous Attorney General Michael Lauber had not made universal jurisdiction cases a priority, but that his successor Stefan Blättler, who took up the post at the beginning of 2022, has reversed this and asked parliament for more resources. Meystre agrees that the new prosecutor seems to be more serious about pursuing international crimes based on universal jurisdiction.

TRIAL International is also raising questions about the timing of developments, says Meystre. The Attorney General’s office issued an international arrest warrant for Assad in November 2021, just after he fled France back to Syria. The Federal Office of Justice (FOJ) refused to unveil it, saying Switzerland was not competent to do so since Assad was neither a citizen nor a resident in the Alpine country and no Swiss were among the victims of a 1982 massacre in Hama, Syria, in which he is accused of playing a leading role. Such a refusal from the FOJ was outside its competence, according to Meystre. Indeed, the Federal Criminal Court ruled in August that Switzerland did have jurisdiction, on grounds that prosecutors first opened an investigation in 2013 when Assad was staying in a Geneva hotel, and it ordered that the arrest warrant be unveiled.

Asked if it might not be a coincidence that the latest developments have come just as the chances of Switzerland getting the accused to trial are slim, Sassoli said he has no information to make him believe that. “But if they are doing this only for show, that would be very serious – although the deterrent effect for others would subsist.”