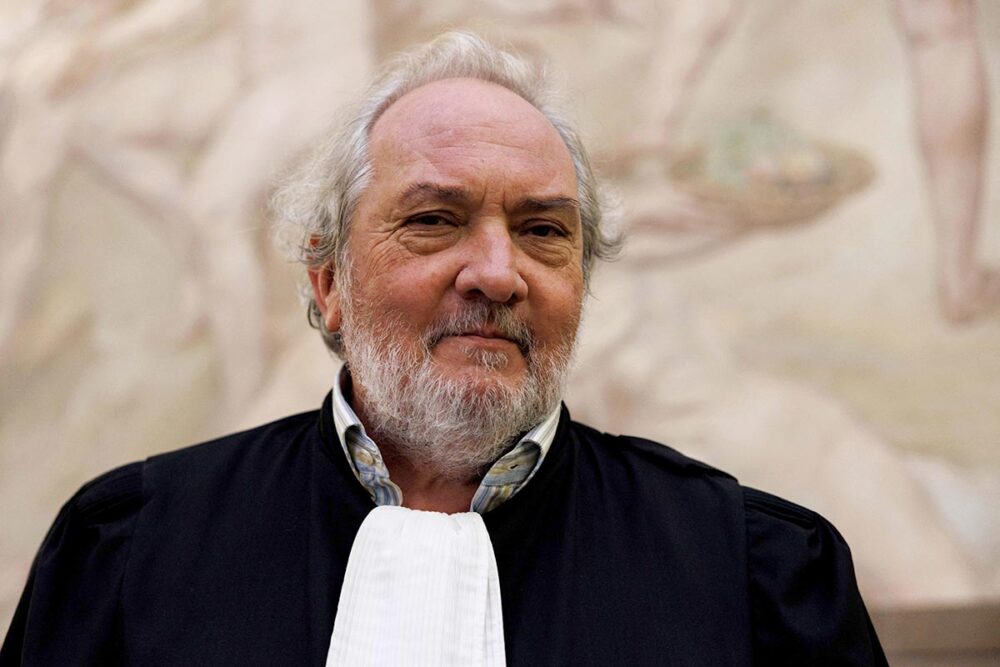

Vincent Lurquin talks to us in a relaxed way, not afraid to be frank. A lawyer for 40 years, he first specialised in immigration law, before defending accused persons before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in 1999. At the same time, he began a political career at local and regional level in Brussels, first with Ecolo, after the party adopted a clear line in favour of regularising undocumented migrants, and then with DéFI, a party in the center of the Belgian political spectrum.

But while being jovial and bon vivant, the lawyer is pessimistic.

The discussion begins and his speech contrasts with the good humour of this informal meeting at Troisième Acte, the restaurant below the imposing Brussels courthouse favoured between noon and 2pm by gourmets of the small judicial world. "The investigations conducted by Belgium into crimes committed during the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, under the law on universal jurisdiction, are polluted by considerations of a purely political nature," says Lurquin bluntly. "Today, the foreign policy of Paul Kagame [strong man and president of Rwanda for nearly 30 years] hangs over these trials organised in Belgium against presumed génocidaires. The Rwandan justice system is not independent. The problem lies in having an international justice system that cooperates with dictatorial countries."

"A truth chosen by Kigali”

As president of the Movement against Racism, Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia (MRAX), Lurquin travelled to Rwanda in August 1994. "A number of us from various human rights organisations were among the first to go to Rwanda after the genocide. We made it as far as Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but we entered Rwanda via Uganda. There were a million refugees in Goma. It was a struggle for survival. Everyone was running to Goma, and in Rwanda there was no one! My first vision was of the little church in Nyamata [in southern Rwanda]. We pushed open the door and there were hundreds of dead bodies, people who had been dead for weeks. I also saw mass graves still open, full of bodies," he recalls with emotion.

"In the case currently on trial in Brussels, the Belgian examining magistrate did not investigate," he believes. "It was the Rwandan public prosecutor who carried out the investigation and pointed out to the Belgian judge the people to be questioned. And the magistrate went to see these witnesses in the presence of a member of the Rwandan public prosecutor's office. She did not look for defence witnesses. So I don't think it's respectful of the rights of the defence, and it's not respectful of the victims either, to have the truth chosen by Kigali. In trials that matter for history and remembrance, the history must be well written. What we are doing today in these Belgian trials is no longer judging the genocide, but supporting the Kagame regime."

We move closer the telephone which is recording in the noisy environment of conversations and clinking cutlery. "For example, you have witness hearings that are conducted solely in Kinyarwanda, without an interpreter, in the presence of the Belgian examining magistrate,” Lurquin continues. “How do you expect her to understand anything? These hearings are then transcribed and sent to Belgium, where they are translated into French. It is at this point that the judge knows what the witness has said, without having any opportunity to question them on it. Imagine that! This is nothing more than a semblance of justice.”

Nostalgia for international justice

The lawyer sits up and tempers his words. "That doesn't mean that international justice can't work or that we shouldn't continue to judge genocide," he says.

The 64-year-old recalls the years he spent defending accused persons at the ICTR in Arusha, Tanzania. There Vincent Lurquin assisted one of the first men prosecuted for the Tutsi genocide, during which at least 800,000 people were killed in Rwanda between April and July 1994. In his view, the fact that the ICTR allowed defence lawyers to investigate on site was a better guarantee of equality of arms between the prosecution and defence.

"My most vivid memory of the ICTR is obviously the first trial I was assigned to, that of Emmanuel Bagambiki, who was prefect of Cyangugu. He was acquitted after eight years of investigation. There the accused had to say on the first day of the trial whether they were pleading guilty or not guilty, then we received a fairly summary indictment, which mentioned in a few words the charges against the accused. After that, the defence and prosecution went their separate ways to gather information. So I travelled around Rwanda for years looking for witnesses. And they came, because we had a real witness protection system. In Belgian trials, the few defence witnesses travel on the same plane as the prosecution witnesses and stay in the same hotel," he tells us.

Lurquin also found himself "on the other side of the looking glass", as he puts it, when in 2007 he was given responsibility for legal representation of the victims in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Ituri conflict before the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was a "quite extraordinary" experience, he says, but not one that he wanted to prolong. "I found it interesting to include the victims in the judicial debate, which was not the case at the ICTR, but then you had to include them at all levels of the proceedings. I didn't have the opportunity to cross-examine witnesses, for example, or to give information I had gathered that was different from the prosecutor’s," he explains. "I also remember raising the idea of being able to ask not just for individual reparations but also for reparations for the community, such as rebuilding schools, which I believe is essential if we are to move towards reconciliation, but that was not possible.”

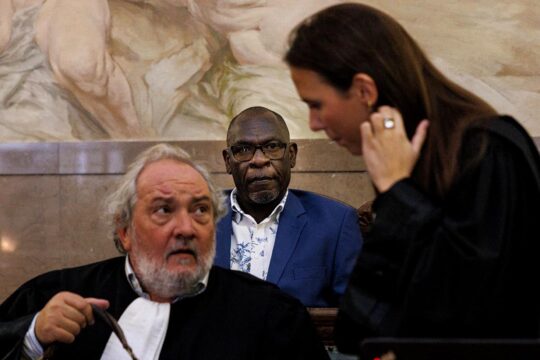

Father-daughter partnership, a new dynamic

So what can still motivate a criminal lawyer, committed to the defence of human rights but somewhat disillusioned, to continue his work in proceedings that he no longer considers effective and fair?

"What motivates me is my daughter," confides this leading member of the Brussels bar.

At the Place Poelaert courthouse, it is increasingly common to see father and daughter side by side. The duo of Vincent and Juliette Lurquin made their debut in a landmark trial in 2022 and 2023, defending a Rwandan accused in the Brussels bombings trial, and then went on to defend Séraphin Twahirwa. When told that the young trainee lawyer is lucky to have the benefit of her father's experience, Vincent Lurquin laughs. "I have to admit that I'm the lucky one to have her. I'm 64, after all," he points out. "In any case, I can see that she has the humanity needed to defend someone accused of the worst crimes.”

Above all, the lawyer feels a duty after what he saw in Rwanda. "It's extremely important to remember all that. We need justice for reconciliation," he says. "Judicial language should be listened to by politicians, because politicians sometimes do exactly the opposite of what we do when we try to dispense justice. That's another reason why I think the people's jury is important when we have problems that affect humanity so closely. Citizens listen to everyone, whereas professional judges no longer do. Juries can judge crimes against humanity, because this humanity is common to everyone. We are dealing with the problem of absolute evil. Jurors realise that we are not judging genocide but people. They say to themselves: 'how would I have reacted?’ -- something that professional judges no longer ask themselves. I think that we must continue to dispense justice in universal jurisdiction trials, but that it is a complicated form of justice."

A quick look at the time. We've gone over schedule. Lurquin has ignored the ringing on his mobile, but this time he gets up and puts on his jacket. "I've got a client waiting for me at the prison," he says apologetically.