In the nineteen eighties, Guatemala was in the throes of a bloody internal armed conflict. The conflict not only took the lives of hundreds of thousands Guatemalan citizens, but also made foreign victims. Among them were four Belgian missionaries who undertook pastoral work with communities on Guatemala’s South Coast. Priest Walter Voordeckers was murdered on 12 May 1980, pastoral worker Ward Capiau was killed on 22 October 1981, and pastoral worker Serge Berten was kidnapped on 19 January 1982. He was never seen again and his body was never found. Pastoral worker Paul Schildermans was detained and tortured in 1982 but released under international pressure. Even though Guatemala’s internal armed conflict ended in 1996, justice for these crimes was never a possibility, as the country became characterized by high levels of impunity.

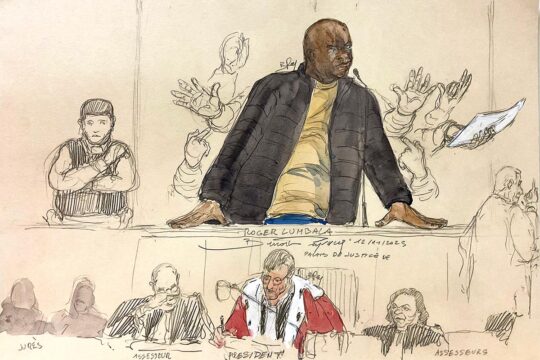

Since Belgium has extraterritorial jurisdiction over the case, as the victims are Belgian nationals, the victims’ family members, united in the organization Guatebelga, eventually decided to file a complaint with civil action before the investigating judge in Brussels. Belgian witness Carlos Colson, nephew of Father Voordeckers, described the action of holding the trial in Belgium in itself as a complaint against the Guatemalan state. After 21 years of judicial investigation, in 2022 the Council Chamber and then the Indictment Chamber referred the case to the Assize Court of Flemish Brabant – the court that tries the most serious cases. On 14 December 2023, after 11 days of hearings, the jury in Leuven decided that the five accused could be considered the intellectual perpetrators of the crimes, and sentenced them to life imprisonment and court costs, ordering their immediate arrest.

Experiences of justice in a faraway country

There are obvious challenges to try crimes that took place forty years ago in a faraway country. How will a Belgian jury understand the historical and cultural context of the crimes? This was an important task for the prosecutors, lawyers, the civil parties, and scientific advisor Prof. Stephan Parmentier. Through the use of Guatemalan witnesses and expert witnesses, who talked about the historical context, the patterns of human rights violations during the armed conflict, and their personal experiences witnessing the violence and persecution in the South Coast, the jury indeed came to understand the context and gravity of the violence. It considered the crimes grave enough to qualify them as crimes against humanity, committed within the framework of "a generalised or systematic attack on the civilian population". One of the Guatemalan witnesses, who lost most of her family members during this wave of persecution, describes this as one of the main achievements in the case: “The interventions by each and every one of us, of situating them [the jury] and giving them the necessary information so that they could take a decision.”

There were however aspects of the trial that were more complicated for the Guatemalan witnesses. Two witnesses told us that, because of the way in which the Belgian judicial system aims to preserve the independence of the testimonies and prevent witness tampering, they had received little prior information about the trial and the proceedings. Being unaware what to expect in an unfamiliar justice system with a very different legal culture generated insecurity among them, and even fear among some witnesses travelling from rural areas in Guatemala.

Language barriers also played a role. Although interpreters translated the witness statements from Spanish into Flemish, this was not true the other way round for the rest of the proceedings, making it difficult for the Guatemalan witnesses to follow the course of the hearings and understand the verdict. The issue of translation has also come up in other universal jurisdiction cases. Language was also an obstacle for receiving psychosocial accompaniment, which is essential in a case involving traumatic experiences like experiencing the death or enforced disappearance of loved ones. The provision of sufficient information about the functioning of the specific justice system and the importance of two-way translation are important insights for similar universal jurisdiction cases, which could help to make these processes more victim-centred and make the proceedings accessible to the population of the countries where the crimes took place.

Justice for them is also justice for us

Nevertheless, both Guatemalan and Belgian witnesses unanimously consider the verdict of great significance. The trial helped to achieve justice for the Belgian victims and make clear that cases of grave human rights violations should be judged, even if the crimes took place decades go and regardless of where the court sits. It contributed to establishing the truth about what happened to the Belgian missionaries, but also about the context of human rights violations in the Guatemala’s Southern Coast, which is still relatively unknown. All three witnesses that we spoke with agreed that the case contributed to the dignification of the thousands of Guatemalan victims. “I feel that this is justice for them [the Belgian missionaries], but also for our families,” said one of the Guatemalan witnesses.

In fact, the jury in its motivation for the verdict explicitly expressed compassion with the victims and witnesses that suffered violence first-hand or lost their family members. This recognition is an important aspect of justice for the Guatemalan witnesses, especially since a similar judgment has so far been lacking in Guatemala, where the justice system has been co-opted by political and economic elites.

The witnesses also express the importance of transnational solidarity for this case. The relationships between the Belgian missionaries, their families and the Guatemalan communities where the missionaries worked, has remained strong throughout the decades. Belgian witness Colson described this solidarity as a motivation for starting the case: “After the peace accords in 1996, we wanted to know the truth. Our first visit strengthened us through the people we saw, the stories we heard and the understanding we gained of this terrible period.” Vice versa, the strong sense of solidarity also inspired the Guatemalan witnesses to travel all the way to Belgium to testify. A Guatemalan witness described the relief and happiness with the verdict among the Guatemalan community members who knew the missionaries well and also lost family members during this same period. Justice in Belgium, remote though it may seem, therefore also feels like justice for Guatemalan survivors of the armed conflict.

Next steps for justice for the Belgian missionaries

The five accused did not cooperate with the Belgian court. They were not present during the hearings and were not represented by lawyers. Angel Aníbal Guevara Rodriguez, former Defence minister and Donaldo Alvarez Ruiz, former Interior minister, are currently fugitives. Pedro García Arredondo, former head of the police secret service, and Manuel Benedicto Lucas García, former chief of staff of the army, are in prison or under military supervision in Guatemala, while Manuel Antonio Callejas y Callejas was recently released because of health reasons.

For a long time, the state of the Guatemalan justice system did not give any hope that a Belgian ruling would make any difference to their position, as more and more human rights cases were facing setbacks, with perpetrators already imprisoned being released. The most that could be hoped for was that the accused would feel restricted in their movement outside of Guatemala, because of an international arrest warrant.

Things might now change. On 14 January, Bernardo Arévalo was sworn in as the new president of the country. Arévalo, an anti-corruption champion from opposition party Semilla, has pledged to restore the rule of law in the country. Restoring the justice system will be a huge task, after years of systematic dismantling in which dozens of independent judges and prosecutors fled the country. Furthermore, Arévalo faces a divided congress, while his party has been under attack by the Attorney General’s Office. But Arévalo can count on strong support from the population and the international community. This might be the first time in years that there is finally hope for justice for conflict-era human rights violations in Guatemala. The Belgian verdict can therefore represent a small impulse for justice at a crucial moment.

Marlies Stappers is the founder and Executive Director of Impunity Watch. She has been deeply involved in research and policy work related to the fields of human rights, transitional justice, impunity reduction, and strengthening the role of civil society, victims and affected communities in countries such as Guatemala and Honduras, Burundi, the Great Lakes region, the Western Balkans and Cambodia. She is also the initiator and coordinator of the Dutch branch of the International Platform against Impunity in Central America.

Sanne Weber is Assistant Professor in Peace and Conflict Studies at the Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research and teaching address how post-conflict countries deal with their violent past and take steps towards peace and reconciliation. Her particular interest is to understand how conflicts change gender relations and how gender equality can be promoted in the post-conflict situation.