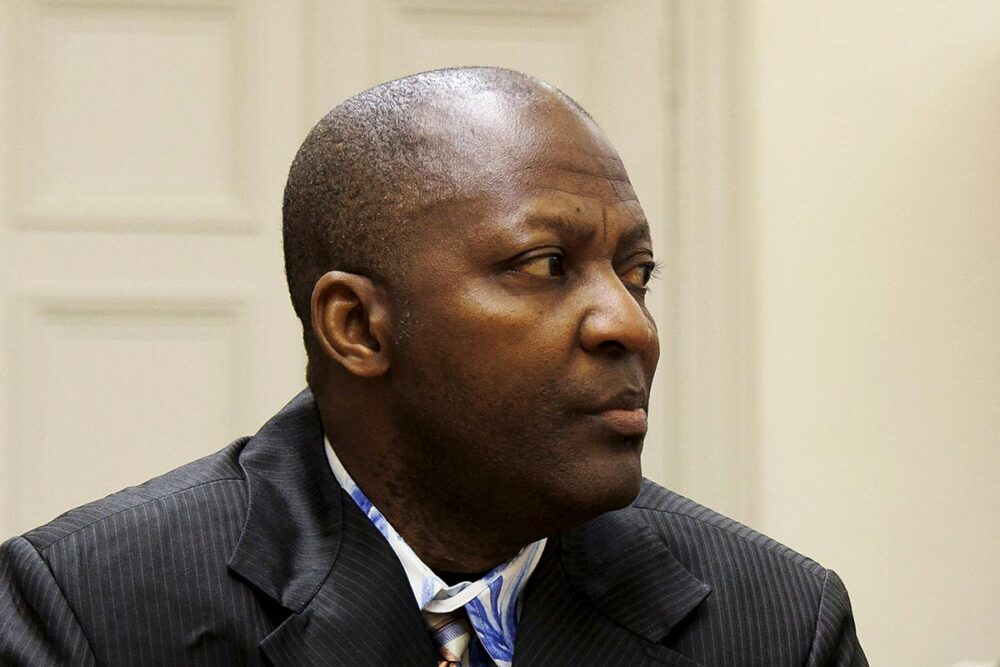

Twice, therefore, the judges have saved Finnish justice from embarrassment. In April 2022, a first chamber acquitted Gibril Massaquoi of all charges brought against him, following a long trial conducted largely in Liberia, where the alleged crimes were committed. On January 31, 2024, after conducting a new trial and also travelling to Liberia, the Court of Appeal came to the same conclusion: acquittal. This judgment puts an honourable end to a case tainted by suspicions of witness tampering - which the court did not wish to investigate - and by major historical contradictions in which the prosecutor had become entangled.

There are few people who would defend Massaquoi. In its final report published in 2004, the Sierra Leone Truth Commission made heavy accusations against this former commander and spokesman of a rebel movement that bloodied Sierra Leone for ten years, from 1991 to 2001. Massaquoi was expected to appear as one of the defendants before the Special Court for Sierra Leone, set up by the UN at the end of the civil war in that small West African country. But he staged a clever operation, becoming the UN tribunal prosecutor’s main informer and obtaining, in exchange for his help securing the arrest and conviction of his former comrades, a form of impunity and family exile in Finland.

When, in 2018, Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima and its Liberian partner the Global Justice Research Project (GJRP) forwarded evidence they had collected, claiming that Massaquoi had committed war crimes and crimes against humanity in northern Liberia and arguing that he could be prosecuted because these facts fell outside the jurisdiction of the former tribunal for Sierra Leone, there was still almost no one to defend Massaquoi. Many even saw this as a just turnaround.

Yet, from the outset of the case, experts on the civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia - interconnected conflicts, with actors playing across an invisible, porous border between the two countries - have been questioning it. At no point was the fact that the alleged crimes took place in question, nor Massaquoi's otherwise violent past. What is in doubt is whether the accused could have been in Liberia on the dates indicated.

Judicial precipice for the prosecutor

What happened during the trial has been described in detail on our website.

Under the leadership of Thomas Elfgren, the unbridled police officer in charge of the Finnish investigation that took over from the NGO one, the Massaquoi case became weighed down with allegations of other crimes, in other places, at other times. But these spectacular allegations are incompatible with solidly documented historical facts. From the moment the trial opened in Monrovia in February 2021, it has been a farce. And no matter how many times the prosecution witnesses changed the dates they had previously given, there was nothing to be done about it. A judicial precipice opened inexorably beneath the prosecutor's feet.

On April 29, 2022, the court in Tempere, southern Finland, unanimously concluded that there was insufficient evidence to convict Massaquoi, either for the crimes committed in the villages of Lofa, in the far north of Liberia, or for the torture of GJRP founder and director Hassan Bility, or for killings and rapes in the capital Monrovia.

It is rare for a prosecutor to lose a case of crimes against humanity in a universal jurisdiction trial in Europe. For him and the NGOs, it was a bitter setback. So they decided to double down: they appealed and asked for a new trial, based on a prosecution theory that had the merit of no longer being contradictory in terms of dates, but which still deliberately ignored certain historical facts.

Sixty-one days of hearings, including 43 in Liberia, were held between January and September 2023. Ninety-seven witnesses and three experts appeared again. All this culminated, on January 31, in a new verdict of acquittal, which appears harsher than the first, if the press release published in English is anything to go by.

Massaquoi "was not in Lofa County"

With regard to the crimes judged, the Court wishes to point out that “It has been proven that the major part of the acts described in the charges have actually happened. In Lofa County there had been committed several murders and other acts of violence, including acts of sexual violence, described in the charges. Furthermore, civilians had been coerced to forced labour and corpses of dead persons had been ill-treated. The above-mentioned acts had been perpetrated between August and December 2001. In a village called Klay a person mentioned in the charges had been subjected to torture as described in the charges. This had happened during the latter part of July 2002. In Monrovia there had been committed several murders and other acts of violence, including acts of sexual violence, described in the charges, between the 1st of May and the 18th of August 2003".

Some of the murders in Lofa and Monrovia have not been proven, but that does not alter the essential point: the atrocities described are real, known and documented.

But the Court of Appeal confirmed, like the court of first instance, that "it was not proven that Mr. Massaquoi was guilty of any of the offences he was charged with" and that it deemed "the identifications of Mr. Massaquoi as the perpetrator of the offences to be unreliable". What is more, the evidence suggested that Massaquoi "had not at all been in Lofa County" between August and December 2001, that he was under house arrest in Sierra Leone from March 2003 and that, "rather convincingly”, he was not in Liberia during the period of the crimes committed in Monrovia. Finally, "on the basis of the evidence presented concerning his presence in Freetown in July and August 2002", the Court considered it “fairly unlikely” that “the accused had been involved in the above-mentioned acts of torture in Klay" of Bility, the director of GJRP.

Substantial reparations expected for Massaquoi

“It was an especially delicate case for both Civitas Maxima and its Liberia-based sister organization the Global Justice and Research Project (GJRP), as GJRP’s director Hassan Bility was himself a witness in the case,” wrote the Swiss NGO in a press release issued shortly after the verdict.

It was also a delicate affair for the Finnish specialized investigation teams and the prosecutor's office, who have been weakened by the affair. The unease is likely to increase further when it is known how much compensation Massaquoi will be awarded, in accordance with the law, for his detention and other damages.

The only one to have come out of this well is the Finnish justice system which, through its judges, has managed to avoid a miscarriage of justice.