"We're not going to give up," said jurist Jean-Pierre Massias, president of the Institut francophone pour la Justice et la Démocratie (IFJD) during his speech in the Victor-Hugo room of the French parliament on February 1, 2024. Invited by the Gauche Démocratique et Républicaine group, the IFJD presented its report on "Indian homes" in French Guiana – the nine Catholic boarding schools which, between 1935 and 2023, interned 2,000 Amerindian children from this colonized territory that became a French overseas department in 1946.

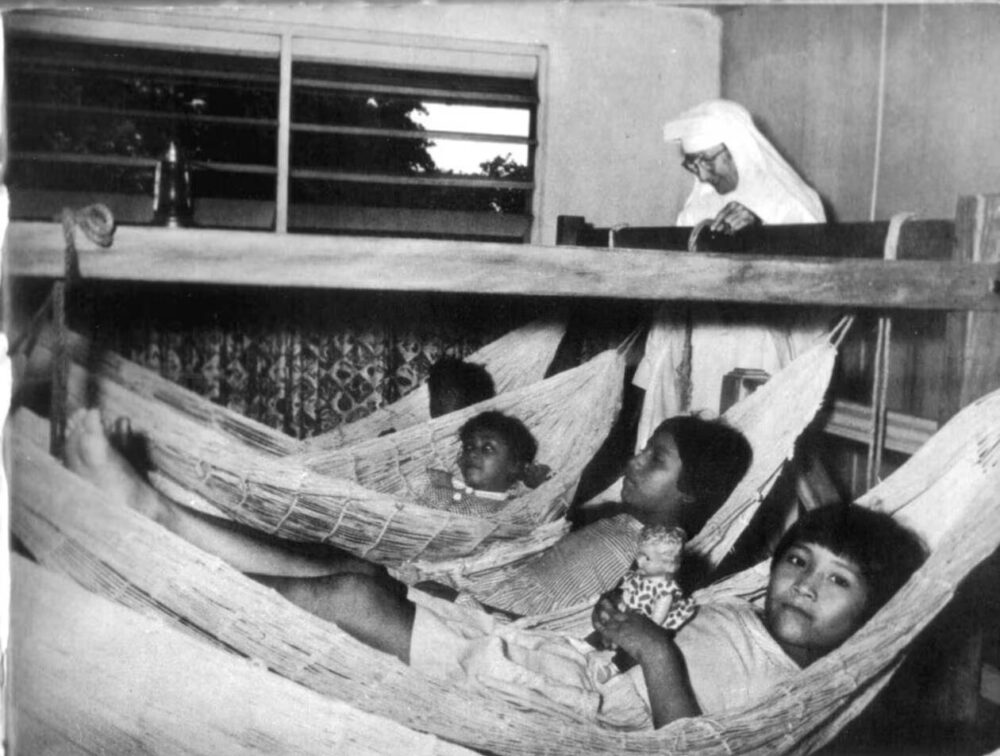

Under the guise of providing a religious education, these boarding schools - or "Indian homes" - contributed to forced assimilation and erasing the identity of indigenous Amerindian and Bushinengue peoples - or "Black Maroons", descendants of African slaves who had fled the plantations. This is a part of colonial history that had remained almost in the shadows until September 2022, when journalist Hélène Ferrarini published her investigative book "Allons enfants de la Guyane - éduquer, évangéliser, coloniser les Amérindiens dans la République". "The aim of my work was to consolidate the historical foundations and answer questions in order to gain an overview, as we were faced with a historical vacuum," explained the journalist at the presentation of the IFJD report on February 1.

"It was up to us to get to grips with this subject," says Massias, lynchpin of this Institute specializing in transitional justice. "There are important and urgent reasons to set up a thorough investigation, leading to a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in view of the testimonies revealing violence and trauma that cannot be ignored," he explained during his presentation.

Customary Grand Council reverses its position

However, this presentation should not have taken place in Paris. "We would like to apologize to those who were offended by the fact that this meeting was not held in French Guiana. These choices were beyond our control, and we were forced to revise the project," says Magalie Besse, director of the IFJD. This stage of the process taking place in French Guiana was considered "essential to enable its orientation and future appropriation, particularly by indigenous communities", says the report.

On January 13, 2023, the Grand Customary Council of the Amerindian and Bushinengue populations of French Guiana had mandated the IFJD to investigate the violence suffered by indigenous people in these Indian homes. "This council was created by the law for Real Equality in Overseas France, adopted in 2017. It enables indigenous populations to participate in local decision-making bodies, but it has no financial autonomy, its budget being allocated by the prefecture [the State local administration]," explains Camille Guédon, former department head at the Interdepartmental Mission for Amerindian and Bushinengue populations, which is integrated into the prefecture.

But "just as the agreement [between the Grand Council and the IFJD] was due to be signed, on March 3, 2023, we received a brief email from the President of the Customary Grand Council informing us that the partnership had been suspended," Besse recounts. "After several weeks with discussions and procrastination, no clear reason emerged and no solution was found." The investigative work had to stop.

"I think this opposition comes from the prefecture," Ferrarini told Justice Info. "The French state has subcontracted this job to the Catholic Church, as the 1905 law on separation of Church and State does not apply in French Guiana."

Contacted by Justice Info, Customary Grand Council President Bruno Apouyou declined to comment on the matter. However, in an article published on the Mediapart website (dated April 15, 2023), he explained this about-turn by the structure of the council: not being a legal entity in its own right, it could not sign an agreement or finance a third-party organization. The prefecture, which declined to answer our questions, is said to be behind the obstruction.

The French state has a responsibility for not wanting to resolve this inglorious part of its history, thinks Guillaume Kouyouri, a former resident of the Iracoubo home and member of the Collectif guyanais pour la mémoire des homes indiens. Contacted by telephone, he explains that the structure of the Customary Grand Council is not adequate to carry out this project. "It's a sham to have put us together. You can't speak for the Amerindians and the Bushinengués at the same time; we don't have the same language, the same history. I think the state has done this on purpose so that we can never demand accountability."

"This report is a wake-up call"

This project was initiated by a meeting in 2019 between IFJD and the late Alexis Tiouka (he died in December 2023), defender of indigenous peoples at the UN and founder of the Federation of Amerindian Organizations of Guiana. This former nursing home resident had already called in 2013 on the occasion of Pope Francis’s election for the creation of a Truth Commission, in an article entitled "Churches and Amerindians, a duty to remember". During a study day at the University of Guiana in December 2022, four recommendations emerged, including the idea of a commission focused on reparations and the creation of a collective for remembrance of the Indian homes. Between January 27 and March 5, 2023, the Institute carried out two missions and a dozen interviews, which, in addition to the 40 or so interviews conducted by Hélène Ferrarini, fed into the report presented in Paris on February 1.

"The methodology consisted in listing the three types of violence: structural, linked to the colonial nature of the State as applied in Guianese schools; cultural, with a coercive assimilation mechanism; and physical, with the use of violence against children," explains Massias. "This report is not an accusation, either against the State or the Church, it is a wake-up call."

Need for more support

While he explains that it "is only one solution amongst others", the experienced jurist clings to the idea of a commission. "This would allow us to reflect on the violence, the causes, the consequences, the reparations and possibly the measures to be taken to ensure non-repetition," he says. And he cites experiences in Canada, the United States (A truth commission between Maine Abenaki and Maine Child Welfare, which submitted its report in 2015), Australia, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Massias also draws on a French precedent. Officially called the "Temporary Commission for Information and Historical Research", the Vitale Commission was created on February 9, 2016, by order of the French Ministry of Overseas Territories. It documented the forced transfers of Reunionese children to France between 1963 and 1983 to populate the French départements. It is considered the first true example of a truth-type commission in France.

"The need for a truth commission on Indian homes is no longer in question," says Philippe Vitale, professor of sociology and former chairman of the commission that bears his name, in an interview with Justice Info. "However, we need the political will to set up commissions like the one I chaired. I think that the lawsuit brought against the State by Jean-Jacques Martial, one of the [Reunionese] victims in 2001, the report by the Inspectorate General of Social Affairs in 2002, and the wave of media coverage and associative pressure from the Reunionese 'transplanted' that followed, contributed to the setting up of the Commission. So, in addition to the political will, there have to be elements that favour it, or even force it a little, such as a trial, media coverage, pressure from associations."

Thus on February 19, 2014, a resolution - not binding, but allowing an MP to bring a concern before Parliament - by Ericka Bareigts, then an MP and subsequently Minister for Overseas Territories, acknowledged the State's moral responsibility in the transfer of Réunionese minors. Two years later, the Commission was created.

A question of time?

Lacking local or national political support, the idea of a truth commission on homes in Guiana remains at the symbolic stage. "The aim of presenting this report was to create an electroshock," explains Jean-Victor Castor, MP for the Mouvement de décolonisation et d'émancipation sociale (Movement for Decolonization and Social Emancipation) in French Guiana's 1st constituency, who has taken up the issue and is trying to get it into the French parliament.

"The more political, associative and legal support we have for this process, the further we will be able to go in pursuing the investigations," adds this man who, during his election campaign, called for a reconciliation process involving all the communities and inhabitants of French Guiana. "This commission will see the light of day with or without the State, with or without the Church," he asserted on February 1.

Kouyouri thinks the fact that a Guyanese MP has taken this up marks a first step. "We're not just asking for recognition, we're asking the French state to apologize and give us the means to rebuild.”

In French Guiana, Ferrarini explains, "the indigenous populations are not all at the same stage on this. There are different time scales,” she continues. “People on the coast, where the homes closed in the 1980s, are ready, willing and able to move on. But for the people affected by the Saint-Georges-de-l'Oyapock home, which closed four months ago, it's too early. In Canada, the process began 20 years after the last residential school closed.”

A petition with 512 signatures "for a truth commission on Indian homes" is circulating. "We've been waiting 135 years. The fact that the process has been set in motion is already a great thing,” says Kouyouri with patience. “Now it's up to the French government to react.”