Fruit trees in bloom perfume the meadow where Mevloud Kharazishvili is lying down, in this market-garden region of Georgia bordering Russian-occupied South Ossetia. On April 23, 2023, the 53-year-old Georgian is tending 26 cows in Tchvrinisi, an isolated hamlet of some 30 souls. Tchvrinisi isn’t on the maps, but here, as in most villages along the demarcation line inherited from the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, a handful of families cling on -- to their piece of land, their stone and tin-roofed house, or whatever they have.

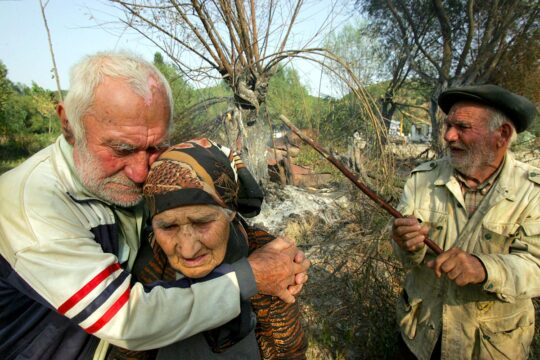

Melvoud is with Elsa Gagaladze, his Ossetian wife. There’s also Bobby, their white dog with no pedigree. When two Russian soldiers suddenly approach and unleash their German shepherd on the couple, Bobby doesn’t hesitate. He sinks his fangs into the hound’s back, never letting go, and drives it back to Ossetia. This gives a brief psychological advantage to the Georgian, who recounts the scene almost a year later, his body still bruised from the fight. “What are you doing here? I’m on the right side!” shouts Mevloud. “We don’t give a damn, you’re killing our people in Ukraine!” barks the masked Russian who seems to be leading the attack and who, on this spring day, has taken it into his head to capture a citizen on the other side of the winding divide imposed on a mixed, intertwined Ossetian-Georgian population. Everyone has family on both sides. A few months earlier, Elsa’s mother, 83-year-old Olia Tsarazishvili, went to fetch an escaped calf from the village opposite, where everyone knew her, and Ossetian policemen brought her back smiling.

One of the soldiers shoots between the Georgian’s legs, then tries to knock him out with a rifle butt, kicks him with boots and tries to strangle him with the German shepherd’s leash. Mevloud defends himself with his bare hands. His broad shoulders contrast with his small stature. They enable him to resist. He clings to a bush while one of the soldiers tries to pull him to his side of the border, which is just a ditch at the end of the pasture. The other one goes for Elsa. But she too struggles like a she-devil, biting the soldier and drawing blood, throwing the tape with which he tried to gag her into a copse. The unequal struggle had been going on for 25 minutes, Mevloud reckons, when at last the 4x4s of the Georgian police, tipped off by neighbours, rolled up, sirens blaring and engines smoking.

No one wants an armed confrontation. The Russians run back to their base, whose roofs Mevloud shows us from the balcony of his house.

Barbed wire, a green sign, a stretch of river

But the Russians maintain the tension. In 2023, according to the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM), 35 Georgian citizens including two women were detained in Tskhinvali, the capital of South Ossetia, on March 11, 2024, four of whom remained in custody. That’s an average of three people a month. According to testimonies gathered by Justice Info in several border villages, the captives are forced to sign a document stating that they have crossed the border illegally, then are taken before a judge in Tskhinvali. The border is imprecise, marked by barbed wire, a green sign in the middle of a field, an embankment, a stretch of river, a section of road, or a ditch as in Tchvrinisi. It can be crossed inadvertently, but border guards know the limits and speak of “kidnappings”. The Russians patrol here, making their presence felt; the Georgian forces keep their distance, clearly anxious to avoid altercation.

At the Tskhinvali court, captives are fined, or imprisoned if they “re-offend”. Physical violence and insults are the order of the day during arrest, in Russian military bases or in the damp, blind basement of a temporary detention centre known as an “isolator”. They are released after a few days, weeks or months. The rule is that there are no rules, or that they shift.

Statistics vary from year to year: in 2015, the worst since the 2008 war, there were 163 “illegal arrests”, according to figures from the Georgian State Security Service. In total, there have been nearly 1,500, according to the same service. In 2018, a man died under torture in Tskhinvali. On November 6, another was shot dead. The line is guarded by border guards from the Russian Security Service (FSB) and the South Ossetian Security Committee (KGB), says the Eurasianet news site. The Russians regularly move the line several metres. This process is known in Georgia as “creeping occupation”. The current government in Tbilisi, whose acts show increasing affinities with the Moscow regime, believes it cannot fight it.

Intervention by the ICC Trust Fund

Border incidents such as the one involving Mevloud and Elsa “are frequent and unrecorded, with official figures showing only the number of people captured and released”, explains Nino Baloiani, psychologist and coordinator of the local office of the Georgian Centre for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims (GCRT), based in Gori - the capital of the Shida Kartli region in northern Georgia, which was attacked in 2008 by the Russian army and its allies. These incidents, she says, create “permanent stress” among border workers, which over time translates into “physiological degradation” and “endocrine disorders” in areas deserted by public services and by the younger generation. She speaks of a strategy of “psychological terror” on the part of the Russians, designed to “push people to leave their lands and villages”.

In relation to this conflict, fourteen years after the 2008 fighting and while another Russian war of aggression was breaking out in Ukraine, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for three Ossetians in March 2022, and pointed the finger at a deceased Russian general. The suspects, protected by Moscow, will probably never stand trial. Anticipating this, Georgian civil society has long campaigned for the activation of the ICC Trust Fund for Victims under its so-called “assistance” mandate, which is independent of a judicial decision by the Court. The Fund finally pledged to do so in November 2020, but the programme did not start until April 2023. According to its managers, this was because of the time needed to conduct a “rigorous, open and competitive call for proposals process”.

This delay makes Nika Jeiranashvili, one of the leaders of the Georgians’ plea to the ICC in The Hague, sigh. “The assistance mandate theoretically means they could start helping people who were already dying. Especially the most vulnerable and the witnesses, because they were old people who couldn’t flee in 2008 during the war,” he says. “They were already dying when the investigation started, eight years after. The Trust Fund took so much time. I invited board members who came to see the victims. Again it took so much time. And this is because of internal bureaucracy. It could have been done years before.”

Scott Bartell, the person in charge of the Fund’s Georgia programme who is based in Kampala, Uganda, told us by phone that it took them two years to conduct “a very thoughtful tender process” to select the two local organizations responsible for implementation.

“A drop in the ocean”

GCRT, which has been working in the Shida Kartli region since 2010, is one of two organizations selected by the Fund. And broad-shouldered Mevloud is one of the first beneficiaries. “We take care of the victims of the 2008 war, who are mainly internally displaced persons, and the new victims of this war, like Mevloud, who live in places isolated from the rest of the world,” Baloiani explains.

The team is made up of doctors, including a general practitioner and two psychologists, and a lawyer who helps with administrative procedures and resolving land disputes. Since it began in April 2023, says Baloiani, the programme has taken 78 people for treatment in Gori, at an average cost of 200 euros each. Field trips, numbering 21 last year and 11 since the beginning of 2024, have enabled the team to carry out consultations, group therapies, but also workshops with young people led by a partner NGO, Indigo. “What we’re doing in the region represents less than 5% of the needs, it’s a drop in the ocean,” admits Baloiani.

In these ageing and impoverished villages, inhabitants say they have been abandoned by the state. Mevloud recounts how, after his misadventure, the police took him to hospital in the nearby town of Kareli. He was discharged after three days for lack of funds, faced with a staggering bill of 1,100 laris (around 380 euros). “The state did nothing for me,” he says. At the GCRT, it was Sopo, a general practitioner, who took charge of him. “He spent two weeks in bed, and when he was able to get up we took him to Gori for an MRI. He was multi-traumatized, with lesions on his shoulders and legs, a dislocated jaw, a concussion and headaches that still prevent him from sleeping,” Sopo recounts, as she examines him in Tchvrinisi, in the main room of the family home furnished with the bare essentials. The sound of a rooster crowing and then of a chainsaw pierce the thin glass, drowning out the hum of the wood-burning stove. “Since then, I’ve woken up every morning as tired as if I’d been working like a donkey all day,” adds Mevloud, who now tends only to his garden. The very existence of the hamlet has been undermined: the cows have been sold, as nobody wants to risk taking them out to pasture.

Maguli, “star” of Ergneti

In the village of Ergneti, home to around 200 households just a stone’s throw from the capital of South Ossetia, another beneficiary of the Fund welcomes us. Destitution is no longer the order of the day. Maguli Okropiridze is famous for giving birth to her daughter in Gori on August 8, 2008, the day the war broke out, and jumping from a bombed-out hospital window with her newborn in her arms. She has become an NGO star, a necessary and indispensable cog in the wheel of their activities in this village, where the EUMM’s blue Toyotas regularly roll in and conciliation meetings between the parties to the conflict punctuate the seasons. Maguli has received “income-generating” grants from the ICC Fund.

Before we begin our interview, an energetic and laughing Maguli sets up a table laden with food and drink. “The village is dying, with no trade or activity,” she laments, as she sits down. The stress is permanent. At night, floodlights from the Russian military base shine in through her bedroom window. She describes the problems of Internet, telephone and television, “jammed by the Russians”. Gunshots and explosions are heard if the Russians are drunk or disgruntled, as in December when Georgia was granted candidate status for entry into the European Union. Kidnappings are frequent here too. “People are scared, they don’t know what to choose. They don’t want Russia but they want peace, so they don’t know if they want the EU either.”

Maguli gets up and leads us into her greenhouse. She shows us the “ICC” rototiller, which sits at the entrance. The greenhouse comes from another programme, she explains, as do the rose and tulip plants. Her house, she says, was built after the 2008 bombings with funds from the Danish Refugee Council. And the farmhouse in the courtyard will be repaired by Project Indigo. As she answers our questions, Maguli signs a contract with a UN project manager. Maguli also takes us on a tour of a “war museum” set up by a neighbour. We ask her what she thinks of the ICC investigation. She remembers former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s visit to Ergneti, “a lady with big lips, who talked to a lot of people and gave us information”. Maguli laughs. She’s seen others. These people come and go.

Forgotten priority: income-generating activities

One criticism of the Fund heard in Georgia is that it has not sufficiently targeted “income-generating activities”. The traumas of the war are long gone, and while many border residents are traumatized by more recent kidnappings, the vast majority of South Ossetia’s 30,000 displaced people are struggling to find an activity to make a living. “I’m not saying that psycho-social assistance isn’t necessary, but when we published this study with civil society entitled ‘Ten years after the August war’, our priority recommendation for the Fund was to focus on the economic difficulties of the victims, and to emphasize their empowerment. If the ICC not only fails to deliver justice, but also fails to address this, that’s a problem,” says Tamar Oniani, Human Rights Programme Director and Deputy Chairperson at Gyla, the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association.

At the GCRT headquarters in Tbilisi, Marika Antadze explains that 11 beneficiaries, all women like Maguli, received a micro-business grant worth 1,000 euros. “It’s almost nothing,” admits the project coordinator. The second NGO selected by the Fund, the Global Initiative for Psychiatry - Tbilisi (GIP-T), does mention an organic agricultural development project with a partner association, Elkana. But GIP-T, which covers the more central regions of Mtskheta and Tianeti, where many displaced people have settled, has concentrated on medical and social aid, explains its director Nino Makhashvili. Between May 2023 and January 2024, her organization provided 300 medical and psychological consultations to direct beneficiaries, she says. Of the 600,000 euros spread over three years promised by the Fund, GCRT and GIP-T have each received 100,000.

These amounts remain modest. They concern a limited number of beneficiaries that is in the hundreds, not in the thousands or tens of thousands like the victims of the 2008 war.