Night has fallen when Nika Jeiranashvili opens the high, faded-blue, wrought-steel gates of the family home in Kolagi, a two-hour drive from the Georgian capital, Tbilisi. Under the arbours covered with climbing vines crackles a fire of vine branches, ready to cook the generous shashliks (pork skewers) piled on a stainless steel dish, arranged on a barrel. Nika smiles, the air is fresh and humid. The international lawyer turned bio winemaker has swapped his elegant suits and coloured ties for a grey knit sweater, more suited to the chill of this late winter in Kakhetia. The region produces 75% of the wines of Georgia, the birthplace of the world’s wine where the first vines are said to have been planted 8,000 years ago.

“I’m happy here, I breathe, I get up early and I work hard, but I never feel tired like I did all those years of battling with the ICC,” says like a joyful admission the man who fought to take Georgian civil society’s case before the International Criminal Court (ICC). It was in the ICC’s cold glass and metal corridors that I first met Nika, with his grand moustache and immutable politeness, in September 2017. The Georgian jurist had been pacing the Court’s offices, scrutinizing its ups and downs, since the opening in early 2016, of the ICC investigation into the 2008 Russia-Georgia war, which resulted in 20% of Georgia’s territory being de facto occupied by Russia. Funded for the first year by the American Soros Foundation, he soon set up his own organization, Justice International, “for greater flexibility in our advocacy with the Court and with States”. For the ICC, Nika was the figurehead of the coalition of Georgian organizations representing victims, and for Georgians, he was the unofficial spokesman for an ICC that in fact had none.

“The first time someone thanked me for what I did”

In the white smoke around the fire, Andro, his father who is a former military prosecutor, and Nina, his wife and head chef in Tbilisi, take turns greeting visitors whilst keeping an eye on the shashliks cooking. A childhood friend his father Vano who has never left the small village of Kolagi chides Vano on how the skewers were crafted. Wine and food are a very serious business in Georgia, and nothing really profound can be said without the ritual of the table and the rhythm of tamadas, the toasts given by the host. The table, set on the first floor of the ancestral building, is simple and generous. A door separates the room from the kvevris, the clay jars buried in the ground where wine is traditionally made in Georgia. The family home, with its rustic comforts - “we’ll fix it up later,” says Nika with a gesture - was furnished in Soviet chic by a grandfather who was a governor.

Nika’s pride and joy is in taking over the wine-making, which was started “136 years ago” by a great-grandfather on the small family estate known as Kolagis. “That’s our story. His name was Nika, I am named after him, and am now the one trying to continue,”he says. Three years on, and after a catastrophic 2023 season in terms of weather, the business is “not at all profitable", he says, with its three to five thousand bottles a year, for six distinct cuvées. But his winegrowing neighbours have embraced him, he smiles, and in particular Zura Mghvdliashvili, a pioneer of natural wine whose amber, fruity bottles Nika lets us taste. Like his pupil, Zura is modernizing old grape varieties, building on the recent success of a festive wine called Pet’ Nat (Pétillant naturel, in French on the label).

“It’s hard because in the beginning you’re building your business, your brand, people don’t know you, you don’t have experience, you’re making a lot of mistakes,” says Nika. “The good thing is that I found one of the top wine makers. He knew me from TV, he knew my work. When I met him he thought it was just for fun, didn’t see me turning my back on everything. I said no, I stopped. Then he was shocked, and he said ‘you have done so much for the people and for the country, so I will help you. I will share all my knowledge and experience with you, I will tell you things that I would not tell anybody else’. Without him I would not be at this level, it would have taken me at least five more years. So I guess my former life helped me here. That was maybe the first time somebody said thank you for what I did.”

The tasting continues late into the night. Nika talks about the perfection he strives for in his wine, how he fuses it with Nina’s cooking, and is full of praise for the people of Kolagi, with whom he has worked alongside daily for over three years. “Here I meet honest, hard-working people, and I like them. In the village, they respect me because they’ve seen how hard I work, just like them. Nobody is lying or trying to manipulate you. It’s a great relief.”

Ignorance and naivety

The next morning, Nika didn’t go to the vineyard. The weather was cloudy, raining intermittently. The atmosphere is reminiscent of bad weather in the Netherlands, he laughs, sitting by the gas heater upstairs on the veranda overlooking the Caucasus mountains.

Was it difficult to leave the world of international justice? “It was not easy because I had to start from zero,” he replies. “All my education, experience, my name, everything was in this [international justice] field, so you basically lose half of your life. At that time, I was 32. I am 36 now. Then when you go to the vineyard, you start working, you look at nature, you feel so much freedom. When you are sitting in an office, your head is fed with so many negative things, with politics, conflicts, victim stories. All kinds of things, and it affects you. But it was easy in a way, because I was sure. I was 100% sure that it was not right to continue like that.”

Disillusionment grew is stages after his move to The Hague. “Initially you think it’s going to be great, you’re very enthusiastic, then you see what happens in practice,” he continues. “I helped the Court to write the strategy on Georgia, to do a mapping of who is who. I was there all day, I had a pass when I did the mapping. They don’t talk to each other, there is no proper coordination.”

And there was worse. When ICC officials were preparing their first mission to Georgia, he says, “they didn’t even know what language people spoke here, and some asked me if French was spoken in Georgia”. They had been in Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and the Democratic Republic of Congo, but they didn’t seem to realize that this was a different continent.”

Then they went to Russia and came back telling him they thought Moscow would cooperate with the ICC. “They treated us well, they invited us to restaurants,” the ICC officials told him. But what were they talking about, he asks. Did they think they were going to be welcomed with weapons of war? This child of the Caucasus, who has lived through the wars in Abkhazia, Ossetia and Chechnya, couldn’t believe his ears. Moscow dispelled the naïveté of the ICC members a few weeks later by announcing it was withdrawing its signature from the Rome Statute at the end of 2016, just as the ICC Assembly of States Parties was starting.

Incompetence and blunders

Nika’s priority rapidly shifted from obtaining trials to “damage control”. “You realize that of course the Court [in The Hague] is not going to catch any Russian general or Putin. Because first of all it has never been successful. In every [other] situation, the Court failed or even created more problems than before. And that was also the risk in Georgia. I explained this to the Court. Because of the tensions between the ruling party [considered pro-Russian] and the opposition [close to the pro-Western ex-president Saakashvili], the government might try to send the former government’s officials to jail, I told them. If the ICC had made that mistake, this could have provoked a civil war in Georgia.”

Seeing no realistic judicial outcome for this first ICC case “outside Africa”, the jurist helped lead Georgian NGOs’ plea for the ICC Trust Fund to intervene on behalf of victims under its “assistance mandate». The NGOs supported their request with a meticulously documented report, “10 years after the war”, in 2018. The assistance programme did not get underway until April 2023. “Again, it took so much time,” sighs Nika. “And this is because of internal bureaucracy. It could have been done years before.”

Another major plea seemed to have succeeded: the opening of an ICC office in Georgia at the end of 2017. “They did it, but then the head of the field office who was selected was the wrong one. He lied when he said he speaks Georgian. He had a background in Georgia of monitoring borders mission for the EU. An Estonian diplomat.” The office’s action was not very visible. “We were complaining, the guy has not done anything during his first year, just university lectures with students in Tbilisi. We told him ‘do your job, go to the settlements, meet the victims, do some outreach’. And when he did, he went to the wrong people, they were from Abkhazia [displaced from the war of the early ‘90s], not Ossetia [who fled the 2008 war, the subject of the ICC investigation]. Then he spoke in Russian to the victims. I talked to them they were shocked. Imagine you have been living in bad conditions for years, a guy comes from the ICC, you have some hope, and they listened to him. They thought that Russia was so powerful it controlled the court.”

“They live like kings in The Hague”

Nika is in full flow. “When you see this, your perception changes, you already don’t see the institution as professional anymore. You see the people getting high salaries, with all the benefits, and they don’t pay taxes. They live like kings in The Hague, and in reality, what they do is a joke. Everybody knows this problem. It’s not only the Georgia situation. Then you talk to Amnesty, Human Rights Watch, FIDH, who have been working with the Court for so many years. You have to be vocal about this problem, criticize. That is what we did, but most of the time nobody supported us.

“In the NGOs, I had some friends who told me ‘Nika, if I criticize too much and I put my name on it, I would lose my job tomorrow’,” he continues. “But that’s the idea of those organizations, to be loud, to shout and be vocal. The world believes in you organization, so what are you doing? Realizing all this, I told them look guys, it’s not going to work for me. I’d rather go back to my village and I will make wine. This is a system that is too flawed, and I realized I could not change it. I tried. But I can’t change it, because people are too comfortable. It’s not just the money, it’s also because most of them come from countries that haven’t experienced war. They don’t know because they haven’t seen it. They go on missions, meet people and say to themselves, this is serious. But then they forget, have a nice dinner and go back to their country.”

In the latter stages of his life as an international lawyer, Nika began working on the ICC’s Afghan case and was asked to work on the Ukraine case. Then, back in Georgia, he was asked to work as a lawyer with NGOs. “But at this time, because of the political situation, because of the ruling party, there’s nothing really an NGO can do,” he says. “You would just be taking money and basically doing nothing. I don’t want that. After my experience, I would then be the same guy that I don’t like.”

The only concession to his old life is that “sometimes I do translation of legal documents, editing documents, which I can do in the evenings when I come back from the vineyard. Considering I don’t get any money from my wine yet, because it’s still initial stages, you need money to pay the bills”.

Return to roots

Now Nika can’t imagine doing anything else but make wine. “It’s exciting. I feel like I’ve found what I really like doing in my life. In my education everything was very legal, graduating from universities, studying so much and working hard in the field of law, human rights, with the ICC and so on. With wine, it’s different. It’s made me really happy.” However, he can’t help seeing a little further ahead. Using one of his talents from his previous life, he obtained funding from the USAID development aid agency for the Natural Wine Association, founded by his friend Zura, which brings together over a hundred producers in Georgia. He went to New York to meet American distributors, who in turn came to Georgia at the end of February.

“I hope the association will grow and there will be a lot of business deals happening with these small families wineries. Then it will influence a lot of things,” Nika says thoughtfully. “In Georgia wine is our thing, very deeply rooted in our tradition. Because of Soviet times, it has been ruined, because there was no demand for quality, it was all about the quantity, how many litres and bottles you produce. Then when the Soviet Union collapsed, they continued this trend, especially big companies, selling the worst wine to Russia. It was not good wine. After that, there was the Russian embargo, the 2008 war, and that’s when we started to really work on the quality of the wine.”

Making good wine in today’s Georgia is perhaps one of the only honest and realistic ways to change mentalities, Nika thinks, not just blaming the government for what it doesn’t do but getting back to roots - his own and those of his country.

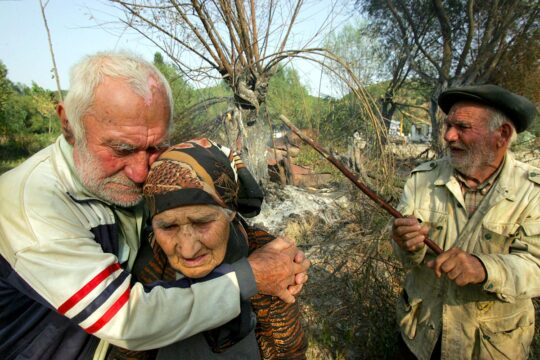

![“I’m happy here, I breathe, I get up early and I work hard, but I never feel tired like I did all those years of battling with the ICC [International Criminal Court],” tells us Nika Jeiranashvili, who is reviving the family vineyards at Kolagi, in Kakhetia, south-east Georgia. Photo : © Franck Petit / Justice Info Nika Jeiranashvili tells how he went from international justice expert to wine expert in Georgia](https://www.justiceinfo.net/wp-content/uploads/Georgie_Nika-1_@Franck-Petit-Justice-Info-1000x666.jpg)