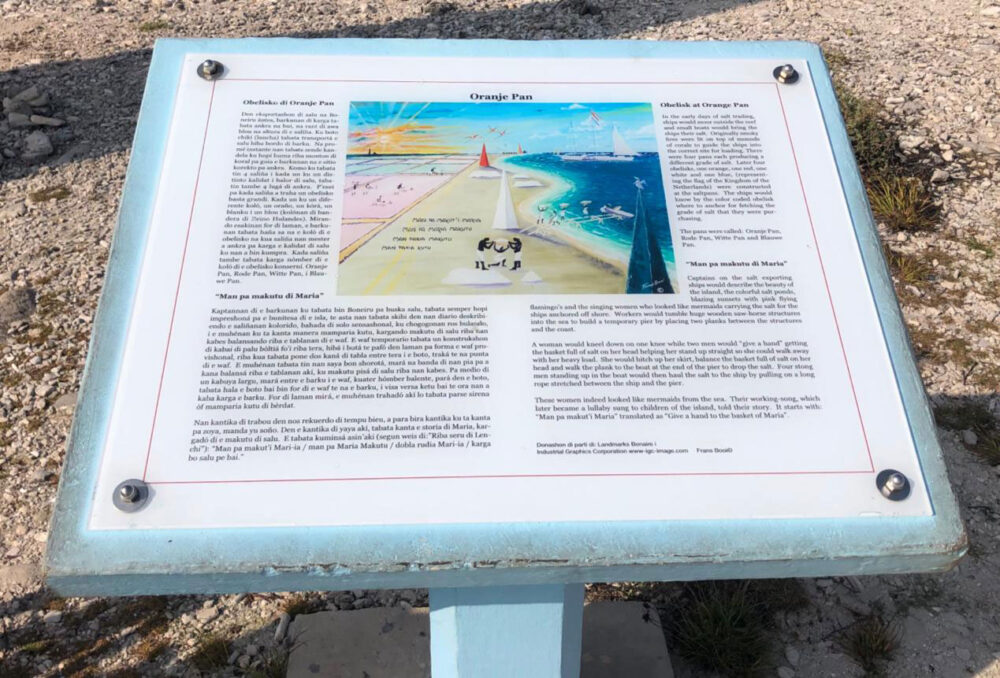

The plaque stands adjacent to the ‘slave cabins’ (kasnan di katibu, in Papiamentu, the local language on Bonaire’s island), shelters for enslaved individuals built from 1850 to 1863 as lip service to those criticising the living conditions of slaves. It depicts enslaved laborers toiling in the saltpans – vast, pink-hued pools where seawater evaporated, leaving behind crystallized salt. And it bears the following inscription:

“Captains on the salt exporting ships would describe the beauty of the island, the colourful salt ponds, blazing sunsets with pink flying flamingos and the singing women who looked like mermaids carrying the salt for the ships anchored off shore. (…) These women indeed looked like mermaids from the sea. Their working-song, which later became a lullaby sung to children of the island, told their story. It starts with ‘Man pa makut’I Maria’ translated as ‘Give a hand to the basket of Maria’.”

The plaque presents a captain's dreamy perspective of the island's beauty, with a notable emphasis on mystical portrayals of women's labour. But in a time where the Netherlands likes to stress its commitment to human rights and has expressed the desire for reckonings with its colonial pasts, accentuated by the Dutch king's apology for the country's historical involvement in slavery in July 2023, the depiction of the ‘slave cabins’ on Bonaire seems peculiar. While discussions about the treatment of colonial-era monuments, plaques, and statues are prevalent in the Netherlands, at first sight they seem notably absent in this ‘special municipality’ within the Kingdom, some 7,796 kilometres away from Amsterdam.

The plaque's portrayal of history near the ‘slave cabins’ reads like a romanticized story rather than a historically responsible reflection. It does not acknowledge essential elements of the enslaved individuals’ history, such as their origins and the harsh conditions of their enslavement. It doesn’t recognize the Dutch role in Atlantic slavery, and the wealth it brought to Dutch economy. Frans Booi, the Bonairian writer responsible for the plaque’s text, may have aimed for a creative touch, but the absence of such information contributes to obfuscating this crucial part of history.

Salt, slavery and struggle

Initially under Spanish rule in the early 16th century before the Dutch forcibly took control in 1636, the island has remained a Dutch colony until 1954 - except for a brief British occupation in the early 19th century. Since then, it has functioned as an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, and since 2010, it has held the status of a 'special municipality'.

During the 17th to the 19th centuries, Bonaire's economy was largely centred on solar salt production, with saltworks dispersed along its coastline, especially in the southern regions. Enslaved Africans and their forced labour played a central role in Bonaire's salt industry. Most of the enslaved people on the island were ‘owned’ by the island’s Dutch government. They worked on the saltpans, all located at the southern end of the island: the Rode Pan (Red Pan) the Blauwe Pan (Blue Pan), the Witte Pan (White Pan), and the Oranje Pan (Orange Pan), corresponding with the colours of the Dutch flag and its pennant. Archaeologists Ruud Stelten and Konrad A. Antczak argue that in 1863, when slavery was abolished, 758 enslaved individuals gained their freedom, 607 of whom had been considered the government’s property. Many of them remained working at these saltpans as paid laborers, sometimes under circumstances of coercion.

Working in the saltpans was incredibly tough. As the seawater evaporated, it left behind a thick layer of sea salt that had to be broken up using pickaxes and other tools. Workers then carried the salt further onto the beach in heavy bags or containers, under the blazing Caribbean sun. Reports from 1854 show that many of the workers in the saltpans suffered from ‘salt wounds’ and scurvy, which were caused by the harsh conditions they endured. The intense heat and blinding reflection of the sun's rays often led to salt blindness.

Avoiding history

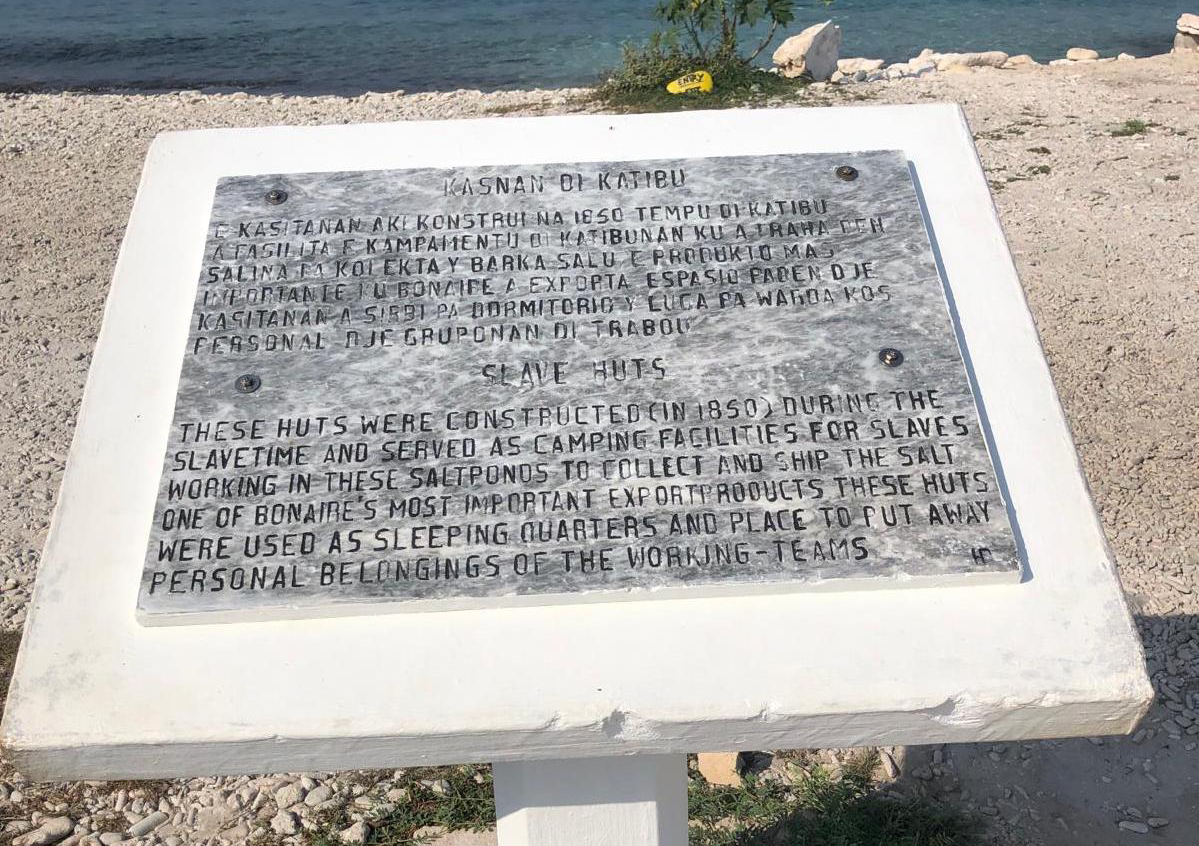

The plaque near the ‘slave cabins’, which is situated near the Oranje Pan, exemplifies the broader lack of historical context provided at significant locations across the island. Another plaque next to similar ‘slave cabins’, situated near the White Salt Pan, offers scant information. It explains how the cabins were built “during the slave time and served as camping facilities for the slaves”. “Slave time” suggests that slavery was only natural at the time, as if people didn’t question the inhumane living and labouring conditions even then. The description does not acknowledge the identity of the enslaved and agency of the enslaver, nor the harsh labour regimes. These outdated terms uphold the whitewashing of this past.

A plaque at the Blauwe Pan states that “although salt production on Bonaire has been happening for centuries, the methods used have changed. Salt harvesting used to be done with equipment including pickaxes, shovels, and wheelbarrows,” it says, while neglecting to provide information about who was (forced to) use these instruments, when, and why.

The information provided at significant historical sites is not only lacking and outdated. It often manipulates history by sanitizing it, without perpetrators, only faceless victims. This representation prevents a deeper understanding of historical events and hinders genuine reconciliation efforts. It suggests that Bonaire’s colonial past has faded into obscurity, as if it has been forgotten or worse, that it does not matter. The ‘slave cabins’ may appear as mere relics of a distant era that no longer hold significance to anyone.

However, the outdated ‘official narrative’ on the plaques is being challenged by unofficial updates. Like this graffiti that declares: “For the second time in history, you steal our island.” Such messages are rare to find, but they show that the colonial past is an indelible imprint that, depending on where one looks, continues to shape the experiences of people living and visiting the island.

Perpetuating inequalities

In fact, Bonaire’s past and present collapse into one another. While addressing the past, the graffiti's message exposes the stark economic disparities that plague the island today, with almost half of the local residents living in poverty. Journalist Phaedra Haringsma sheds light on this “crisis in slow motion”, revealing the struggles of Bonaire’s residents, who receive significantly less social support than their European counterparts. As the cost of living on the island surpasses that of the Netherlands, Bonairians are left with far less disposable income. Dutch dominance in access to resources and opportunities is growing on the island, echoing historical injustices.

This unequal access to resources is exemplified by the housing market on the island. Since 2010, when Bonaire became a municipality within the Netherlands, wealthy Dutch people have found it easier to relocate to the island, driving up housing prices significantly. The high prices of food are largely due to the island’s heavy reliance on imported goods, predominantly from the Netherlands. While tourists and affluent immigrants can afford these prices, local residents face financial strain. They are priced out of these essential resources, perpetuating disparities and inequalities.

“A segregated society”

The consequences of the unequal access to resources are evident, with residents, news platforms and government organizations regularly reporting on. Bonairians, they show, are compelled to skip meals, resort to overcrowded living situations, and must juggle multiple jobs to make ends meet.

Haringsma speaks of a “segregated society”, where divisions persist not only along economic lines but also indirectly along racial lines. Differences in spending power is one of the reasons why Bonairians generally tend to visit different places – hair salons, cafes, restaurants - than tourists or Dutch immigrants. While the latter enjoy exclusive beach clubs, indulging in traditional Dutch snacks like ‘bitterballen’ and ‘kaasstengels’, Bonairians might gather in the local pub in the village Rincon.

Discontent about Dutch dominant presence extends beyond graffiti on rooftops. Over the years, activists have protested by placing wooden signs along the main roads. One sign reads, “1863 slavery abolished. Free from the Netherlands. Help now or (re-)colonize. Many fewer Makambas” (person born in the Netherlands). Another sign was placed by James Finies, founder of the Nos Kier Boneiru Bek (We Want Bonaire Back) organisation. It suggests, among other things, that “Settlers Dutch Makambas” should “go home”, and that Bonarians live under “Dutch Apartheid”.

It is important to mention, however, that a large majority of the population is not so expressly preoccupied with the question of whether the island should become independent. The interests of the island are too significant to cut ties with the Netherlands, as argued by political scientist Wouter Veenendaal and historian Gert Oostindie. Discontent primarily revolves around the poverty and inequality on the island, a sentiment that was also evident in street protests in May 2022 and 2023.

Hope for the future

Bonaire’s hidden colonial history is not so concealed when looking beneath the surface of the official texts provided at historical sites. The enduring weight of the colonial past can be found in the form of criticism expressed at these sites and along main roads. It can be found in the island residents’ disparities in resource access and in Dutch disinterest towards their concerns.

Slowly but surely, there appears to be a growing recognition of the need for accountability regarding the erosion of Bonaire's economy and culture. In 2024 the Dutch government allocated an extra €30 million for poverty alleviation in the Caribbean Netherlands. Part of this funding aims to increase social welfare benefits, reflecting steps towards establishing a social minimum on the islands.

Of particular interest is the collaboration between the Bonairian Terramar Museum, local heritage organizations, and Utrecht University in the Netherlands which aims to redefine the narrative surrounding the island's heritage. Instead of an “exhibition for cruise tourists”, the project is advocating for a permanent postcolonial exhibition by and for Bonairians.

Even if the outcome of extra social funding and Terramar’s plans for an exhibition are still unclear, initiatives such as these give hope for a future with a more conscientious approach to history.

ANNE VAN MOURIK

Anne van Mourik is a PhD candidate at the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and the University of Amsterdam. Until 2020 she worked as a researcher in the ‘Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia 1945-50’ program. Together with Peter Romijn, Remco Raben and Maarten van der Bent she worked on the research project about the ways politicians and colonial administrators dealt with large-scale violence. Her current research explores victimhood/perpetrator discourses with regard to German hunger during and after both world wars.