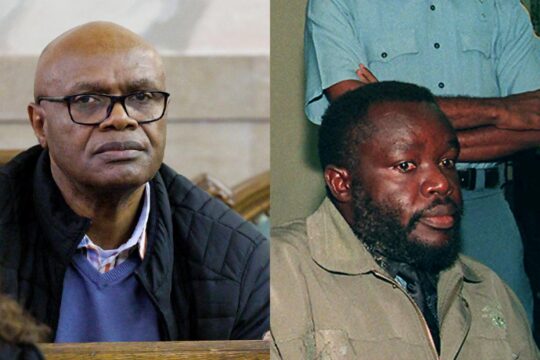

On Monday May 13, the Brussels Assize Court had to do without the testimony of a key witness, Paul Rusesabagina. The former manager of the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali, who lives in the United States, refused to testify by videoconference and explain what he knows of Emmanuel Nkunduwimye’s activities during the Tutsi genocide between April and July 1994. Rusesabagina, whose story is famous and inspired the film Hotel Rwanda - a successful work of fiction recounting how this manager of the Rwandan capital’s main hotel took in and protected over a thousand Tutsis and Hutus threatened with massacre, knew well Nkunduwimye, currently on trial in Belgium. According to the investigation, between April and May 1994 he transferred to the hotel numerous people threatened with death, in exchange for payment. Nkunduwimye was also said to have regularly come to the hotel to sell food and drink from the loot, in the company of his friend Georges Rutaganda, vice-president of the National Committee of the Interahamwe, the militia that spearheaded the genocide.

Should Nkunduwimye be regarded as a self-interested saviour, or as an accomplice of Rutaganda and his militia who might have participated in the massacres while sparing the lives of some if there was the scent of money? This is a question that the trial is trying to clarify. However, its efforts are increasingly being undermined by the absence of key witnesses.

The accused’s version is that he supplied the Hôtel des Mille Collines sometimes without being paid, aware that the most important thing was to help all the refugees there. But how can we verify this? He also said that Rusesabagina was not a saviour but a manipulator, driven by money. What does Rusesabagina have to say about this?

The big absentees

All these questions remain unanswered. After the genocide and his exile in the United States, the former hotel manager became a fierce political opponent of Rwandan President Paul Kagame. The success of the film made him a hero, and he was received by the American president, giving him a remarkable public platform and arousing the ire of the Rwandan authorities. In 2020, deceived by Rwandan intelligence services, he was forcibly returned to Rwanda, imprisoned, tried for terrorism and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He was released and deported at the end of March 2023, thanks to negotiations between the US and Rwanda.

Not knowing Rusesabagina’s version of his regular contacts during the genocide with Nkunduwimye and Rutaganda (sentenced to life by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, ICTR, in 2003 and deceased in 2010), obviously hampers the debate. Back in April, the court deplored the absence of two key witnesses to the genocide, former top Interahamwe leaders Eugène Mbarushimana and Dieudonné Niyitegeka. Parties to the trial were expected to put many questions to these two men, whose testimony was eagerly awaited as they were respectively Secretary General and Treasurer of the Interahamwe National Committee.

Mbarushimana, who lives in Belgium, did appear in the witness room, but could not be heard given that an investigation by the Belgian Federal Prosecutor’s Office suspects him of personal involvement in the genocide. The court did not want to take the risk that he might incriminate himself in his own case by testifying in this trial. As for Niyitegeka, who lives under protection in Canada after having collaborated intensively with the ICTR prosecutor, he ultimately refused to testify, even by videoconference.

Risk of proceedings being inadmissible

But these three major absences are not the only ones. Many other witnesses were unable to be heard for various reasons. The court deplored the death of some of them between the dispatch of summonses and the start of trial on April 8. It also received several medical certificates for very elderly witnesses whose frail health prevented them from being heard. Others simply did not show up. These defections were so palpable that, on April 24, none of the three witnesses scheduled to be heard that morning turned up. Twenty minutes after starting, the hearing was suspended for the rest of the morning. And so, with the end of trial scheduled for the end of May, around a third of the witnesses called have evaporated.

The defence was quick to react, pointing out that reading out the statements of absent witnesses during the investigation does not replace a hearing in the context of an adversarial debate, and contravenes the sacrosanct principle of oral proceedings in the Assize Court. “Are we still in a position to judge?” asked lawyer Dimitri de Béco on April 24. “It makes me uncomfortable, Madam President, because I can’t ask the witnesses for certain details which would enable me to know whether what they are saying is what they actually saw or only what they heard. This is obviously very important. We know that with witnesses who came forward, they told investigators in their hearings what they thought they knew about the facts but that they hadn’t actually seen anything."

The lawyer hinted that he was seriously considering asking for the prosecution against his client to be declared inadmissible, given that the defence does not have the opportunity to question witnesses. The risk of a judicial fiasco is very real.