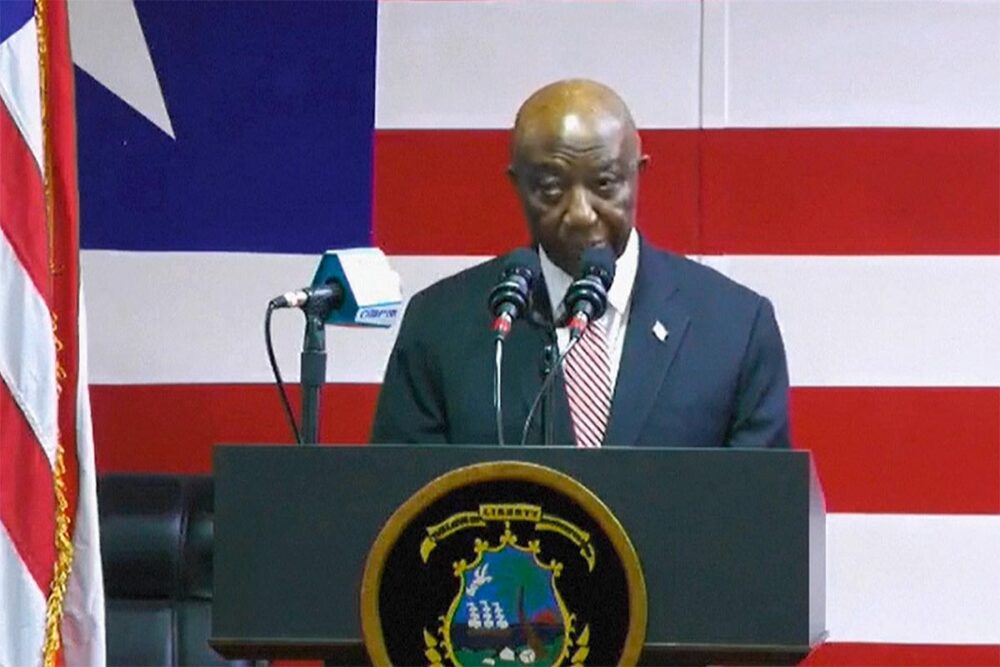

On May 2nd 2024, Liberians in the diaspora and those at home took to social media to talk about one thing: the Executive Order NO.131 creating the Office to establish the War and Economic Crimes Court in Liberia. Liberians on X (Twitter), Facebook and LinkedIn praised President Joseph Nyuma Boakai for the political will to reckon with Liberia’s past. To say the action was popular would be an understatement. In Liberia’s transitional justice history, May 2nd 2024 may go down as one of the most consequential milestones, perhaps a date that deserves to be memorialised.

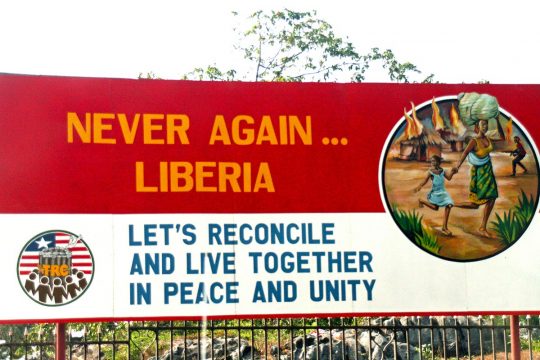

The date marked an end to the politics of silence, legislative manoeuvring on matters of transitional justice and weak political will to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report. Few, however, questioned the idea of the court and whether it would lead to healing and genuine reconciliation.

The passage of the resolution in the Senate makes one telling observation about the nature of post-conflict societies. The farther post-conflict societies transition away from war to peace, the more the fear of relapse becomes remote, emboldening electorates to exercise more freely their democratic rights to remove from office those they chose to. This singular action has proven consequential in successive elections, for it has reduced the influence of some senators and representatives who have served as a roadblock towards the establishment of the Court. Where wartime memory was previously deployed as a weapon, the holding of regular elections provided an opportunity to weed out the good from the bad.

A milestone after the TRC report

The euphoria of May 2nd 2024 is somewhat comparable to June 30th 2009, the date the TRC report was released. In almost the same manner, Liberians everywhere were discussing the report which named the names of senior Liberian politicians (past and present), including an associate justice of the supreme court, several legislators and a sitting president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. In the eyes of ordinary Liberians, the report had broken with the elite tradition of political correctness, which was to avoid mentioning the name of influential people or to mention them very carefully.

That the report was rebellious in naming names, it was considered courageous and an adequate response to Liberia’s enduring culture of impunity, although the legality of the naming process and its infractions with due process remain some of the ongoing critique of the report and the signpost of its many flaws.

However, the difference between the TRC and the War and Economic Crimes Court as two pathways to the pursuit of truth telling and criminal accountability remain a source of confusion. To ordinary Liberians, both are one and the same. The Executive Order establishing the Office on War and Economic Crimes Court makes no specific departure from matters of the TRC and that of the special court. If anything, it reinforces this apparent confusion.

Countering a claustrophobic legal system

According to Liberia's jurisprudence, the Executive Order is a law that lasts for only one year, a legal instrument that can be renewed. It is issued by the president for immediate actions on situations that would otherwise take longer for the legislative process to complete. President Boakai's strategy to use an Executive Order to start the design process of establishing a war crimes court for Liberia is shrewd and might be useful in at least two respects.

First, the Executive Order acknowledges Liberia’s constitutional supremacy. Liberia’s constitution is restrictive and territorial, as its Article 2 points out: “any laws, treaties, statutes, decrees, customs and regulation found to be inconsistent with the constitution shall to the extent of its inconsistency be void and of no legal effect.” Though Liberia has signed and ratified treaties and conventions on war crimes and crimes against humanity, the penal law has remained unchanged and so is the constitution. The legal regime of Liberia is somewhat claustrophobic.

In 2019, working as a member of a civil society collective, I collaborated with the Liberia Bar Association in reviewing a bill on the establishment of a war and economic crimes court. Some of Liberia’s senior lawyers could not imagine a legal process whereby an international court would have a trial chamber higher than the Supreme Court of the country; one that would have the Supreme Court subordinated for the purpose of this special arrangement. Instead, they could only imagine a process whereby the Supreme Court of Liberia stood as the court of last resort. The irony lied in the fact that the lawyers failed to recognise that one of the reasons why international courts are established in post-conflict settings is that judicial systems are compromised, undermined by years of political interference, and lacking in public trust.

The claustrophobia of Liberia’s legal system has shaped and defined the pedantic procedure of law. It has produced a system that is more committed to the practice of law than the application of justice. One of the critical tasks of the Office to establish the War and Economic Crimes Court would be to legally engineer the appropriate statute that explores simultaneously the right marriage between the constitution and this special court. In other words, the Office must envision legally a strategy to break free of this claustrophobia by imposing war crimes and crimes against humanity as part of Liberia’s penal code.

The legacy of the TRC: unreliable evidence

Second, the most important task is to observe a clear break between the TRC and the establishment of the Court. The message contained in the Executive Order tends to suggest that the establishment of the Court is an extension of the TRC, but it’s problematic for the public to perceive the Court as a reincarnated TRC...

In broad strokes, there are two types of TRCs. One is largely organised around pursuit of evidence gathering and facts with the view of supporting future criminal prosecution of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Whereas the other is more about generating dialogues, establishing a consensus over the past, that there were systematic wrongs perpetrated over time. Such truth commission engages in conversation about the future as much as it does about the past.

I like to think of the Liberian TRC experience more in terms of the latter. While the TRC process initially sought to produce a report that resembles the former, it did not have the budget and political support to produce the evidence that would be used as a solid foundation for future war crimes investigations. It means that much of the information supplied in the TRC report was never verified. Many figures, such as fatalities, warring factions responsible and the dates, were all provisional facts gathered. Given the political context at the time, these provisional facts were deployed as advocacy strategy. They served as live ammunition in the fight against the enduring culture of impunity. Now that the advocacy is over and we have the Office of the War and Economic Crimes Court being established, the process of gathering fresh new evidence must be the new focus, because the facts in the TRC final report are not reliable.

In 2022, I conducted 8 group interviews across the country to understand how grassroot communities are memorialising the political violence of the civil war and earlier. One of these interviews was held at the Samay Memorial, one of the most illustrative grassroot memorialisation projects in post-war Liberia. Samay is a small village whose history revolves around the genealogies of four families. The TRC final report placed the fatality of those massacred at 500. But the community insisted that the total number of those massacred was only 42. Engraved in the front of the memorial erected in 2001 are the names of 37 people massacred. The final roll of honour has been updated and it places the total fatality at 42, instead of 500. The community plans to upgrade the memorial by engraving the additional five names.

Another example is the interview I held at the Bloe Town Massacre site, in River Cess County. The TRC Report said the massacre happened in 1995, but the community maintained that incident occurred in January 1994. In the meeting, one of the female participants confirmed the date and indicated that she was pregnant the same year the massacre happened.

The challenge of evidence gathering

What we have here is the social memory of two victimized communities versus the TRC final report. The TRC’s investigations were conducted less than five years after the peace agreement, when villages and towns were still dislocated and residents still internally displaced. Plus, the TRC’s operations suffered from a persistent low budget and never had the resources to validate the evidence gathered. Even when the evidence were validated, it could not be used against those who voluntarily participated in the public hearing process or statements' gatherings. One of the tasks of the Office to establish the War and Economic Crimes Court will therefore be to manage the public expectations.

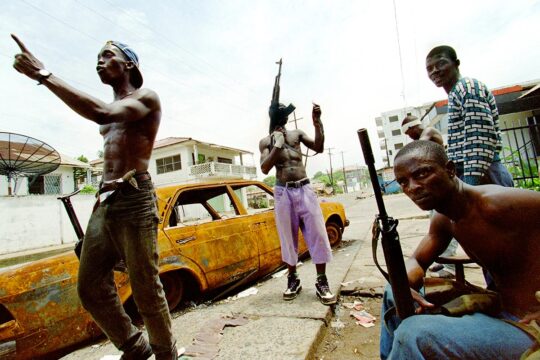

One of the challenges of the court would be evidence gathering. The Liberian society is now stratified between two population blocs, the millennials and the pre-war generation which represents the generation who experienced the violence. This generation with the memory of the conflict is now aging and Liberia is only just starting to look into war crimes, 34 years after the beginning of the war, 21 years after the Peace Agreement, and 15 years since the TRC report recommended the establishment of an extraordinary tribunal on war crimes.

The lapses in time have introduced further complexity. Some of the accounts of war crimes are as old as 34 years. In 2021, I witnessed the Finnish war crimes trial in Liberia of Sierra Leonean Gibril Massaquoi. One of the observations during the trial was the issue of distorted memory. The residents of the villages and towns that claimed to have been victims of Massaquoi’s alleged war crimes could not remember accurately when the specific acts had been perpetrated. If the Massaquoi trial was experiencing difficulties with incidents of war crimes which occurred between 2001 and 2003, imagine the complexity of investigating war crimes perpetrated in the early start of the civil war, from December 24th 1989 to 1990.

The silver-lining: evidence stored at the Georgia Tech Institute

When the TRC report was released, it ignited a firestorm among the elites. Alleged perpetrators, some of them senators and representatives, gathered, convened a press conference on July 6th 2009 and threatened to resume the conflict if the report was implemented. The TRC fearing that the worst was yet to come, gathered the victims’ statements, declassified materials and other evidences and had them shipped to the Georgia Tech Institute, in the state of Georgia, USA. The Memorandum of understanding governing the management of these materials maintained that they could only be returned to Liberia if the conditions to preserve them were favourable.

The strong political will expressed in president Boakai’s Executive Order may have initiated the first major step towards the repatriation of these critical documents. However, the act that established the TRC says the evidence gathered from victims, survivors and perpetrators – which are the same evidence stored in Georgia Tech – cannot be accessed until 20 years after the TRC final report was released. This embargo is meant to protect the identities of victims, survivors and alleged perpetrators who participated and supported the process.

In the Court’s race against time, the Georgia Tech archives might be one of the sites of memory that would be reliable in establishing a solid evidentiary basis for the prosecution of war crimes. The newly established office on war crimes will have to consider the laws around these archives and how to use them. Because the pre-war generation – that now accounts for less than 30% of the overall population – is aging: some are long gone, and some of the sites of the massacres and physical sites of memory are invisible. Under these circumstances, evidence gathering would undoubtedly be a herculean task. Hence, the TRC archives held up at Georgia Tech might be the silver-lining, a site of memory to explore in establishing the evidential basis for the prosecution of war crimes.

Aaron Weah is a civil society activist and a leading expert on transitional justice in Liberia. He’s a final year PhD Researcher at the Transitional Justice Institute (TJI), Ulster University, and Director of the Ducor Institute, a think tank on social and economic research based in Liberia. Weah is a co-author of Impunity Under Attack: The Evolution and Imperatives of the Liberia Truth and Reconciliation Commission.