The Finnish Treasury’s website soberly sets out the four criteria for compensation in the event of unjust detention: expenses directly caused by the deprivation of liberty, loss of income or maintenance, suffering, expenses of application for the compensation. By email, the legal department explains that “the basic level of compensation is 120 euros per day of imprisonment”, but that “reparation can be increased, for example based on the duration of imprisonment, the seriousness of the charges and the level of media exposure. The reasonable amount of the compensation is assessed on a case-by-case basis”.

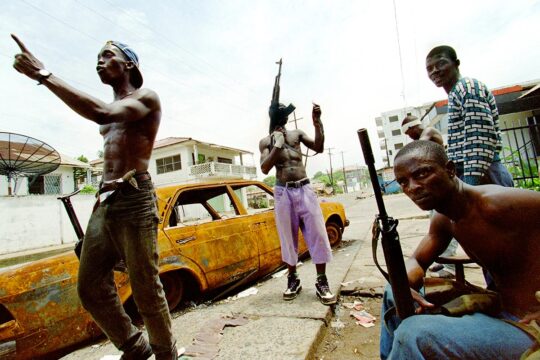

Based on this, Gibril Massaquoi filed a claim for compensation in early May for the 709 days he spent in prison in Finland. In 2020, the former Sierra Leone rebel commander was charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Liberia between 1999 and 2003. He was found innocent twice, in 2022 and again in 2024, by two panels of judges who ruled unanimously. In his application, Massaquoi is now seeking compensation of €1,000 per day, i.e. €709,000, which would be a record amount. To this he has added €106,370.50 in lost income (€4,582.96 per month, calculated on the basis of his tax returns prior to arrest) and legal costs (€850). This would give him a total of around 815,000 euros.

Half a million euros is highest to date

On average, between 400 and 500 requests for compensation are processed each year by the Finnish Treasury. The total varies from year to year, from €1.8 million in 2023 to €3.5 million in 2018. According to data from the Finnish administration, the two largest individual amounts awarded to date have been €511,600 and €520,000 (excluding loss of earnings).

In the first case, a mother, Anneli Auer, had been acquitted twice of murdering her husband in a high-profile case often described as the country’s “crime of the century”. Auer was awarded compensation of 800 euros per day for 611 days’ imprisonment. “That case was exceptional in Finland’s history. I don’t know if we can take that as a baseline for this case,” says Noora Allenius, Head of Legal Services for Citizens at the State Treasury. Another case is that of two Iraqi twins who were prosecuted in Finland for war crimes committed in a camp in Tikrit, northern Iraq. Defended by the same lawyer as Massaquoi, Kaarle Gummerus, and acquitted, they spent 533 days in prison and received 400 euros in compensation per day of detention.

“Hostile and biased” media coverage

The decision on the amount awarded by the Treasury is purely administrative, and takes between two and four months from the date of the request. If the complainant is not satisfied, he or she can lodge an appeal with the courts. Of the 400 or so cases examined each year, only 15 to 20 are appealed to the courts, according to Virva Vesanen, legal adviser at the Treasury. But these appeals are more common in cases that are a bit out of the ordinary, she continues. The majority of cases involve detentions of less than a week, which are quickly closed.

In support of his client’s request, Massaquoi’s lawyer Gummerus cites the length of the detention, the detainee’s age (50 at the time of his arrest), the difficult living conditions of a foreigner in captivity, and the restrictive conditions of detention, including solitary confinement. He also stresses the extreme seriousness of the accusations -- including murders and executions, rape, torture and burning villages --, the level of media exposure and its “hostile and biased” nature, as well as director of investigations Thomas Elfgren’s alleged misconduct.

Investigative material leaked before the trial

Elfgren is accused of having tried to put pressure on Massaquoi over the choice of his lawyer and of having disclosed, before the trial, numerous elements of the case file to Anu Nousiainen, a journalist with Finland’s largest daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. Just before the opening of the trial, Nousiainen published a lengthy incriminating article without seeking the views of the defence, which Gummerus described as aggravating circumstances. “This is not a normal way to treat a suspect in the media,” he wrote in substance on behalf of his client.

“Although the State is not in principle liable for publicity generated by journalistic and social media, it should be noted in this case that the investigator in the case has actively contributed to the negative public image of Massaquoi,” he continued. And he cited the scathing comment of presiding judge Juhani Paiho at the opening of the first trial on February 8 2021: “We don’t need to decide this case when Helsingin Sanomat has already done so.”

While the media impact of a case has clearly been taken into account in the past when estimating the harm caused and setting the level of compensation, allegations against a director of investigations are a less well-established factor. “I am not sure if in case law it has been ruled that this is something you need to take into consideration,” Vesanen comments cautiously.

But whatever reparation is awarded to Massaquoi, it is likely to amount to hundreds of thousands of euros, which will be the stuff of dreams for anyone acquitted after many years in jail by international courts like the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Court. For example, if the former Rwandan minister André Ntagerura -- arrested on March 27, 1996, acquitted and released on February 24, 2004 after spending some 2,900 days in prison -- had been able to claim compensation of 500 euros per day, he would have received nearly 1.5 million euros. But international justice is far less protective of individual rights than Finnish justice: there is no limit on pre-trial detention, nor any financial compensation in the event of acquittal.

Finnish transparency

Finland is not only very protective of the rights of the wrongly accused. It is also unusually transparent about the cost of its legal involvement. In an article published on February 27, Finnish public broadcaster Yleisradio Oy (Yle) reported that the Massaquoi trial was one of the most expensive in the country’s history. From the start of the investigation in 2018 to the appeal judgement in 2024, after two trials on the merits both largely conducted in Liberia itself, the cost came to €3.9 million.

Yle scrupulously details the expenses: at first instance, 583,000 euros were spent on travel to Liberia, 485,000 on the judges’ salaries, 381,000 on legal fees, and 232,000 on translation and interpretation. On appeal, 222,500 euros were spent on travel, 451,000 on judges’ salaries, 352,000 on lawyers’ fees, and 189,300 on interpreting services and witness expenses, excluding the cost of translating the judgment.

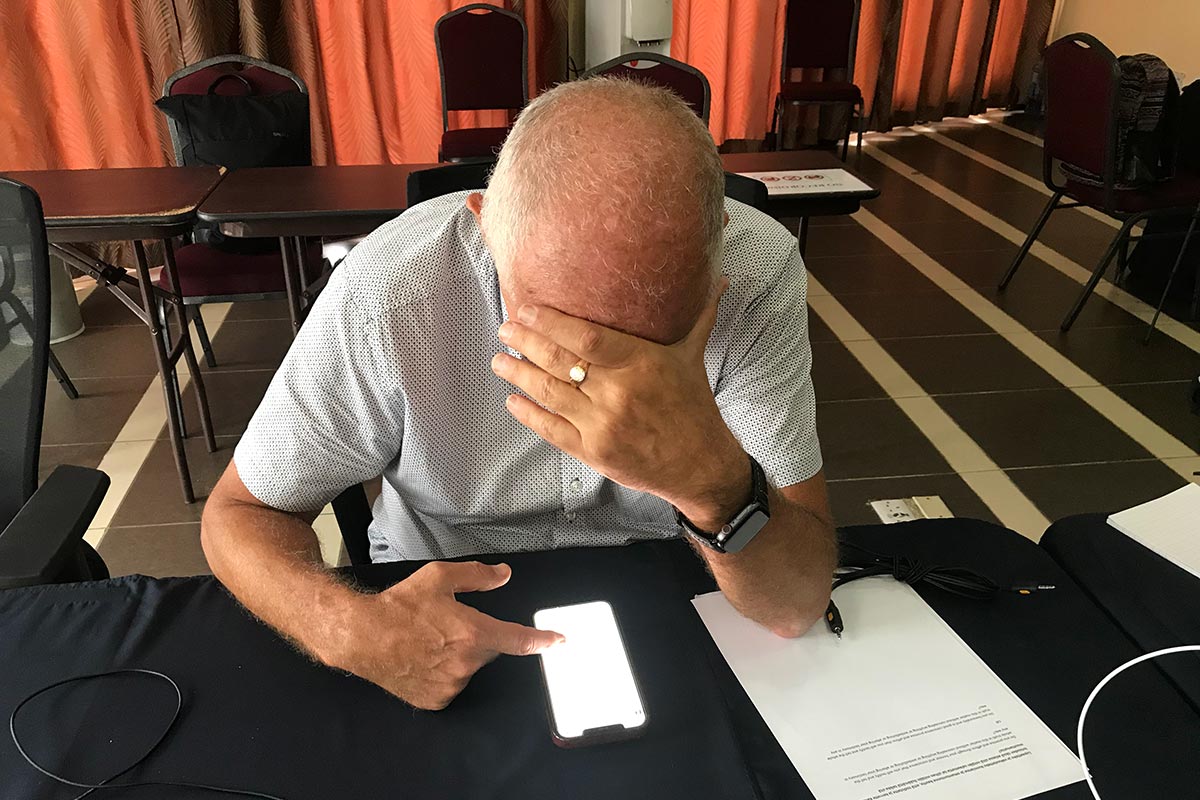

In February, another media article reported on an investigation launched against Thomas Elfgren, the former head of investigations in the Massaquoi case and a key player in its fiasco. Elfgren had hidden in his hotel in Liberia the equivalent of several thousand euros in Liberian dollars, cash that was intended for local spending. But around 7,500 euros were not found in the accounts provided after the operation. Elfgren explained that he had to organize these caches because the hotel’s safe deposit boxes were too small and not secure enough, and the Swedish and European Union embassies had refused permission to store the money. He claimed the missing sum might still be in its hiding place, but an inspection of the premises found nothing. In the end, no charges were brought against Elfgren, who paid back €6,000 before he retired.

Proceedings against two NGOs in Liberia

The reckoning is not confined to Finland. According to the Liberian press, Massaquoi has also taken legal action in Liberia against the two NGOs that initiated the proceedings against him: Swiss organization Civitas Maxima and Liberian organization Global Justice Research Project. The case took an even bigger turn after the appointment of Jonathan Massaquoi as executive director of the new office responsible for setting up a war crimes and economic crimes tribunal in Liberia. Massaquoi is Gibril Massaquoi’s lawyer for his Liberia complaint. Jonathan Massaquoi (no known family relationship with Gibril Massaquoi) is known for having defended other international crimes suspects like Agnes Reeves-Taylor, a former wife of Liberian President Charles Taylor who was convicted of crimes against humanity and is serving a 50-year prison sentence in the UK.

“While every individual has the right to legal representation, the ethical and moral implications of appointing someone who defended alleged war criminals to a position dedicated to prosecuting such crimes cannot be ignored,” writes The Liberian Investigator newspaper in a June 24 editorial. “The coalition [of war and economic crimes court advocates] rightly argues that a person who has defended alleged perpetrators of gross human rights violations is not the appropriate figure to now champion justice on behalf of their victims.”

“Observers have expressed concerns that Massaquoi’s involvement in representing clients, including Agnes Reeves-Taylor in defamation lawsuits, against justice activists such as Hassan Bility of the Global Justice and Research Project, former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Massa Washington, and Alain Werner, head of the Swiss organization, Civitas Maxima, could raise doubts about his impartiality and independence in the eyes of the public,” writes The Daily Observer. According to this Liberian daily, Jonathan Massaquoi is supported by the American Alan White, who has become an adviser to the new Liberian president Joseph Boakai. A former director of investigations at the Special Court for Sierra Leone, White is the man who recruited Gibril Massaquoi as an informant 20 years ago and ensured that he escaped prosecution before the UN-backed court. His animosity and resentment towards the two NGOs involved in the prosecution of his protégé in Finland are well known.