On March 20, 2024, the Italian president Sergio Mattarella paid a tribute to the RAI journalist Ilaria Alpi and her cameraman Miran Hrovatin on the 30th anniversary of their murders in Mogadishu, Somalia, as they were working on a report into weapons and waste trafficking. “The killers and those who ordered the murders are still nameless and faceless after investigations, moves to knock the probes off track, retractions and trials ended in nothing,” he said. “It is a wound for the whole of society. The institutions know that we can never give up on the search for the truth.”

Thirty years ago, on March 20, 1994, Alpi, 32, and Hrovatin, 44, were ambushed and shot in their jeep in the Somali capital by a seven-man commando. Initially, it was thought that the reporters were murdered after clashes which had broken out between the militias of Somalia 's warlords and Italian peacekeepers. But a 1999 book by Alpi 's parents called “L 'esecuzione” (“The Execution”) alleged that they were killed to stop them from revealing what they knew about an international arms and toxic-waste ring implicating high-level political, military and economic figures both in Italy and in Somalia.

Waste crimes. Environmental crimes. They are transnational. They are costly. Their number is rapidly growing. And they are often linked to corporations or to organized crime. “When we talk about environmental pollution, illicit waste management, crimes against nature, we are often dealing with very organized and potentially dangerous criminal groups,” says Rudi Bressa, a Italian environmental journalist and the author of a book on illegal trafficking, Trafficanti di natura. And when you look at the equation environmental crime and organized crime, there is one European country that immediately stands out : Italy.

Last week, three decades after the murders of Alpi and Hrovatin, the Italian environmental NGO, Legambiente, published its latest report. In 2023, 35,487 environmental crimes were recorded in Italy (+15.6% compared to 2022), with an average of 97.2 crimes per day, 4 every hour. These crimes are concentrated in the South of the country, particularly in the four regions with a traditional mafia presence - Campania, Puglia, Sicily and Calabria - where 43.5% of the alleged environmental crimes take place. Among the three types of crimes most committed, the number of recorded incidents in the illegal cement industry continues to rise (13,008 cases, +6.5%), but what is most worrying, reports Legambiente, is the surge in crimes in the waste industry (9,309 cases, +66%). They have risen to the second place, well above wildlife crimes such as illegal poaching, illegal fishing, trafficking of protected species (6,581 cases).

According to Lagembiente, the entire illegal market in Italy was worth 8.8 billion euros in 2023, with 378 mafia clans involved and high levels of corruption that give them access to public markets and tenders. After releasing its report, the NGO asked the Italian government for a serious commitment in the fight against “ecomafias”.

The power of “ecomafias”

First used by Legambiente in 1994, the word “ecomafia” found its place five years later in the Zingarelli dictionary. “By coining the term ‘ecomafia’, we wanted to denounce the perverse intertwining between organized crime, economic crime and, indeed, environmental crime,” says Enrico Fontana, head of the environment and legality observatory at Legambiente.

“We are recording a greater spread of environmental illegality on the territory of our country which ‘accompanies’ that of mafias, in particular the ‘Ndrangheta,” he says.

‘Ndrangheta is one of Italy’s oldest criminal organizations, born in the 18th century in Calabria, and one of the country 's most powerful organized crime syndicates after the fall of the Sicilian mafia, also known as Cosa Nostra. “Although the impunity no longer exists, both the hardships of our judicial system and the direct impact of organized crime in attacking the environment remain,” Fontana adds.

Acoording to Marta Palmisano, a lawyer and criminal law researcher with the universities of Palermo and Torino, difficulties in fighting the ecomafia stem from the fact that organized crime can interfere in parts or in the entire cycle of waste management, from production, provision of services, collection, transportation to processing and disposal of waste.

According to Palmisano, one of the reasons why environmental criminals have chosen the waste sector as a privileged area of activity is the objective complexity that characterizes the management of the waste cycle. Waste has considerable “mobility” within and outside the country, and thus provides numerous opportunities for “infiltration”. This long “waste chain” includes various actors – waste producers, brokers, transporters, warehouses and waste treatment facilities, technicians, companies that legally do business, and even civil servants – who end up collaborating, more or less consciously, with criminal consortia.

“The Italian experience is particularly significant because the fight against the ecomafias is carried out taking into account the specifics of the [national] context, already tragically known to the Italian criminal law literature,” Palmisano says. “The same investigative and judicial tools can be used that are usually used in the fight against criminal mafia association including strong coordination between offices during the investigation.”

The legal weapons at disposal

In order to fight ecomafia and prosecute environment-related crimes, in particular waste crimes, Italy has established a specialized security force for environmental crimes in 1986, which was reinforced in 2001: the Carabinieri for the environmental protection and ecological transition. According to Emanuele Tamorri, the commander of this unit in Rome, the enormous flow of money that comes from illicit activities linked to the waste business in Italy imposes a particular focus on the threat represented by environmental crime, where perpetrators tend to rapidly change their modus operandi.

“Taking into account the revealed versatility of environmental crime, the Carabinieri for the environmental protection have developed a particular investigative expertise which has necessarily had to be extended to further areas, such as knowledge of the operating regulations of the public administration or the regulation of public procurement, the execution of large public works and renewable resources (wind, photovoltaic, geothermal, biomass, biogas etc.), documenting a clear convergence between mafia crime and economic crime, with reference to sectors in which important public investments are expected and are absolutely attractive to the appetites of criminal and mafia enterprises,” Tamorri explains, adding that current Italian laws are capable of effectively preventing and combating behavior that is harmful to the environment.

Over the past 25 years, Italy has developed a robust legal framework to prosecute waste crimes, which could serve as a model for other countries. In 2001, the Parliament approved a law on “the new crime of organized activity of illegal waste trade”, and in 2015, it adopted law 68-2015 that introduced crimes against the environment into the national criminal code.

“It 's not that there is no legislation: the legislation [on environmental threats] is there,” says Anna Sergi, a professor of criminology at the university of Essex, UK. “The problem is the lack of resources to investigate these crimes and sanctions that do not fit the crimes.”

Eurojust: a rise in environmental crime cases

In the European Union (EU), the entity to help fighting environmental crimes is Eurojust. The Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation, based in the Hague, The Netherlands, allows national judicial authorities to work closely together to fight serious organized cross-border crimes, such as environmental crimes. According to their data, there is a 64% increase in the number of environmental crime cases referred to Eurojust in 2023 compared to 2022. “Environmental crimes are usually of a complex, multi-disciplinary and cross-border nature, with national authorities not having the capacity not the resources to effectively detect, investigate and prosecute them,” says Tan Van Lierop, a spokesperson for Eurojust.

“The existence of different legislative and investigative approaches to dealing with environmental crimes across countries also poses legal and operational challenges,” he adds. “Eurojust is supporting member states in the process of clarifying legal definitions and legal terms used to describe environmental crimes, to prevent too much room is left for interpretation, which could prevent prosecutions.”

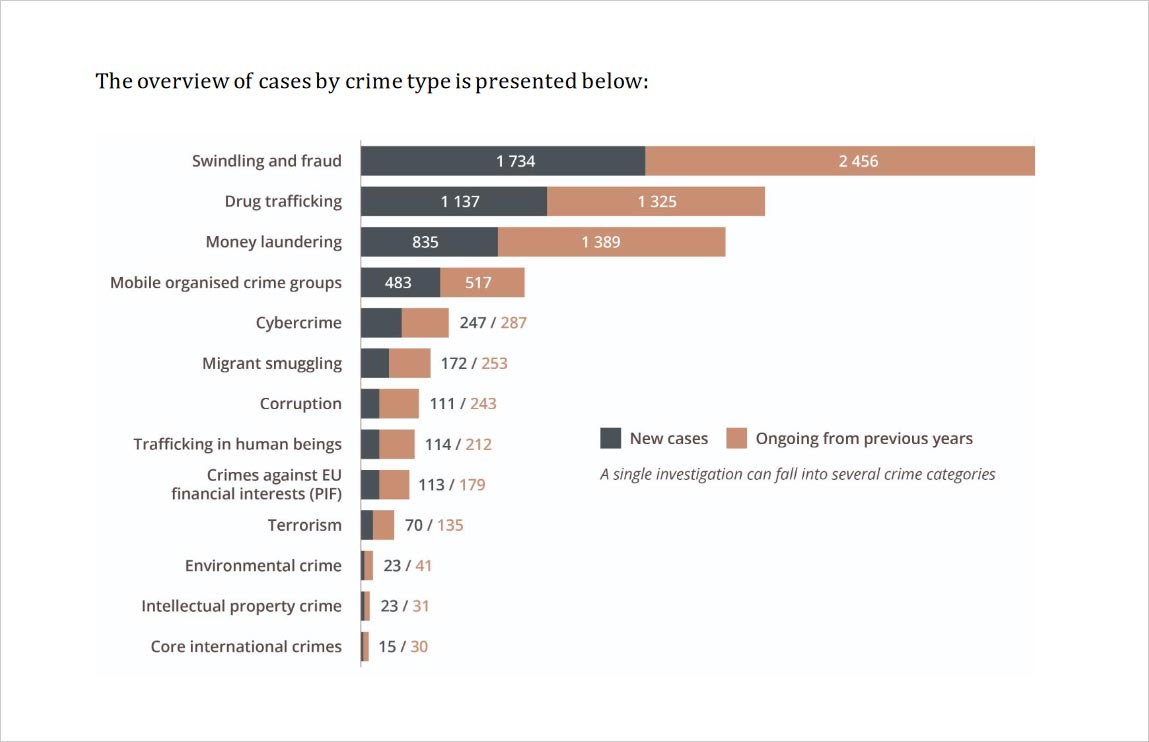

Eurojust doesn’t open investigations. Public prosecutors in EU member states (and of the eleven countries who have liaison prosecutors at the agency) can ask Eurojust for cross-border judicial support when the case they’re dealing with might span several countries. However, despite a 64% increase, the overall number of environmental cases handled by Eurojust remains quite low: only about 60 cases out of more than 13,000 cases across 13 categories of serious cross-border crimes (including fraud, drug trafficking, money laundering, etc.) involve alleged environmental crimes.

Criminal cases handled by Eurojust in 2023

A new EU environmental crime directive

Since the EU has set environmental crimes as one of its priorities in the fight against organized crime, as a part of the European Multidisciplinary Platform Against Criminal Threats (EMPACT) 2022-2025, it has recently addressed the shortcomings of its legal response by adopting new EU rules to protect the environment through the means of criminal law. The new Environmental Crime Directive, adopted in April 2024 and entered into force on May 20th 2024, aims at fighting against the most serious breaches of environmental obligations, with a comprehensive and up-to-date list of environmental offences. Member states will have to ensure that these breaches constitute criminal offences in their national law. They have two years to do so. And they are required to provide annual statistics detailing the number of reported cases of environmental crime and their national strategies used to fight it.

This makes the EU the first regional inter-governmental body to criminalize cases of destruction of the natural environment. An additional step was taken by the Belgian Federal Parliament, which adopted a new penal code that includes the crime of ecocide as an international crime alongside war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression.

But for the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), a network of 180 civil society groups in 41 countries, it is not be enough. “Rising numbers of environmental crimes are a symptom of a failing law-enforcement chain and an ineffective sanctioning regime. Following the European Union’s finalisation of the revision of the Environmental Crime Directive, member states now have till May 2026 to incorporate it into national law”, says Frederik Hafen, senior policy officer for environmental law and democracy at EEB. “While the new law is a major improvement, it does focus on minimum legal standards and adds little in terms of resource allocation to police and prosecutors. Reduction of waste disposal related crime still relies on national political will to establish specialised police and courts and to dish out fines high enough to hurt companies’ balance sheets.”

Could transitional justice help?

In the absence of specialised jurisdictions for environmental crimes, the question now is whether and to what extent transitional justice can be used as an inspiration or directly applied to address environmental crimes committed by organized crime and ecomafia.

Transitional justice was developed to address massive criminality, traditionally in a situation of dictatorship or armed conflict where a great number of human rights violations were committed, recalls Anna Myriam Roccatello, deputy executive director of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ).

“Those situations have taught us that a normal system of rule of law, normal institutions and processes of justice, criminal prosecution, trials, are not adequate because of the sheer number of violations and the seriousness of their nature. So they cannot be sufficiently and appropriately addressed by normal, regular, traditional legal institutions,” she says. “You need a different approach. Not only because of the number and nature of the crimes, but because this widespread violence erodes the basis of peaceful coexistence among citizens and the trust between citizens and state institutions. This is applicable to a large extent to the phenomena of transnational crimes and organized crime.”

“One of the biggest lessons we 've learned is that in order to tackle organized crime we need a set of legislation, a specialized prosecutor 's office and a very robust and highly trained witness protection program,” adds Roccatello. “When it comes to the war against the mafia and similar organizations, Italy is in the forefront of a number of legal and social innovations.”

Roccatello compares the Italian anti-mafia strategy with the practice of transitional justice settings pursuing crimes like genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. “You need very specialized and coordinated institutions,” she says.

But organized crime has the ability to infiltrate society to the extent of co-opting the state, and such phenomenon of criminality can only be reasonably tackled and addressed through processes that are not solely legal and institutional, but also political, reminds Roccatello. She gives the example of Colombia, her country of birth, where the 50-year long armed conflict was deeply rooted in narco-traffic, and “where a peace agreement was negotiated not only with political insurgents or political actors, but also with criminal organizations, which is extremely novel,” and “very divisive.”

More specifically, “you may ask what a truth commission has to do with the illegal exploitation of garbage and illicit recycling or fraudulent disposal of waste,” she continues. “Well, through truth-seeking, you can certainly bring up the voices of all those that have suffered from these illegal activities, hear how communities have suffered in having the waste buried in their fields or the fumes caused by an illegal disposal plant or how they have been trapped in a vicious cycle where the only economic opportunities were to work for this organization or keep silent. A truth-seeking exercise that reveals information required to know exactly how this was made possible, and collect the information you need to address it and correct it, could be valuable,” according to her.

Transitional justice is based on the concept of restorative justice, where the ultimate goal is not to punish per se, but to create those conditions where everyone can accept to live together according to the rule of law, Roccattelo concludes. “So you punish those that are the most responsible, and you find solutions, alternatives, semi-retributive and restorative sanctions for those that were the ‘arms’, those that were recruited into the criminality.”