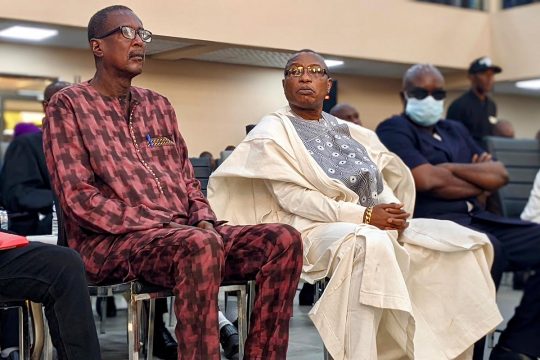

“The court sentences Captain Moussa Dadis Camara to 20 years’ imprisonment.” With his sentence just pronounced, the former president of Guinea wore a frozen smile. The silence was almost unreal silence as the president of the Dixinn criminal court, Ibrahima Sory 2 Tounkara, read out the verdict on Wednesday July 31, after 22 months of trial.

There was no reaction from the audience. Expectations are high, however, almost 15 years after the Conakry stadium massacre, in which more than 150 people died, hundreds were injured and more than 100 women were raped. This outburst of violence during a security forces crackdown on an opposition rally on September 28, 2009, traumatised Guinea.

It should be said that on this historic day, there were many people absent. Most of the victims, still fearing reprisals, preferred to watch the hearing on television. The lawyers’ seats were also empty. Counsel for the civil parties and defence decided to follow a Guinean Bar Association call to boycott the hearings in protest at enforced disappearances currently affecting civil society activists in the country.

Life sentence for fugitive Pivi

In its decision, the court upheld reclassification of the charges as crimes against humanity. Dadis Camara was convicted on the basis of his responsibility as a hierarchical superior. In the end he received a more lenient sentence than requested by the prosecution, which was seeking life imprisonment for the former head of state. Moussa Tiegboro Camara, the head of the anti-drug unit who took part with his men in the stadium crackdown, also received a 20-year sentence. Only one life sentence was handed down -- to Claude Pivi. This man, who was Minister of Presidential Security at the time of the events, has been on the run since his escape from prison in November.

Marcel Guilavogui, the President’s former protégé who was seen beating up political leaders at the stadium, was sentenced to 18 years in jail. Blaise Goumou, a gendarme under Tiegboro’s command, got 15 years. Mamadou Aliou Keita was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment. Paul Mansa Guilavogui was sentenced to 10 years.

In contrast, the court considered that Aboubacar Diakité (known as “Toumba”), Dadis Camara's aide-de-camp and head of the presidential guard, had “distinguished himself by his good faith” during the trial, and gave him a ten-year sentence. He has been in detention since 2017 and could be released within three years. Four defendants were acquitted, including former health minister Abdoulaye Cherif Diaby.

Human rights organisations hailed the verdict as “historic”. According to a press release from the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), “the Guinean judges have sent a clear signal that no one is above the law, and those who commit crimes covered by the Rome Statute will be brought to justice”.

Joy and disappointment

When the court left, there was no outpouring of joy among the few victims present. They expressed their satisfaction in a subdued way. “When you accuse someone in court, you have to be there until the end,” said a young woman who was raped at the stadium and who requested anonymity. “We’re very happy with the court president’s decision. He spoke the law.” She is delighted that the charges have been reclassified as crimes against humanity, which has symbolic significance for her. Eight defendants were convicted on this basis, including the main protagonists of the case: the former president, Pivi, Tiegboro, Guilavogui and Toumba. “It’s a verdict to set an example,” she says. “They did nothing to stop the massacre. All those responsible will have to take their responsibilities now.” Even so, she is disappointed that Dadis will escape life imprisonment, but says she “respects the law”. On the day of the verdict, the judges did not elaborate on the reasoning behind the sentence.

Dadis’s lawyers to appeal

This verdict does not mark the end of the fight for the victims. There will probably be another trial. Dadis’s lawyers have already announced that they will appeal.

It seems that this trial, despite its length, leaves a feeling of unfinished business for the parties. While the issue of security has been at the heart of debates in recent months and a law was passed two years ago to protect the victims, the latter claim that no measures have been implemented by the authorities and that they remain at risk after the judgment was handed down.

The fight for compensation also continues, with the verdict stipulating that it is up to those convicted to pay compensation to the plaintiffs. The amounts are astronomical, especially for people who have been in detention in some cases many years. The court decided to award each rape victim 160,000 euros, 100,000 euros for each death or disappearance, 20,000 euros for each case of torture, for each victim of assault and battery. There is very little chance that these sums will be paid and the court ordered only financial compensation, while the victims suffer from a lack of psycho-social and medical support.

The court’s response on this issue has been heavily criticised by the civil parties. “The State said it could conduct the trial here in Guinea. So it's up to the State to compensate, it's up to the State to assume its responsibilities,” said the same survivor of the massacre.

Unsolved disappearances

The defence greeted the verdict coldly. “This is a dark day for Guinean justice,” commented Pépé Antoine Lamah, a leading member of the Guinean Bar and a member of Dadis Camara’s defence team. He denounced the decision as “iniquitous”, “devoid of any legal substance and handed down in violation of the rights of the defence”. In his view, the charges should not have been reclassified as crimes against humanity. This issue, which caused lengthy debate when it was raised in March, came up only a few months before the end of the trial, and the court waited until the verdict to decide on it.

The trial did not live up to all its promises for the civil parties either. The case still has grey areas: victims have never been found, and the mass graves where soldiers are suspected of putting certain bodies have never been located. Dadis Camara could have helped bring out the truth, but “he remained walled in silence”, laments Alpha Amadou DS Bah, coordinator of the victims’ lawyers’ collective.

107 victims testified

On the whole, this first experience in Guinea of a trial for mass crimes is a generally positive one and a success for the country’s judicial system, which has succeeded in bringing a former president to trial. This alone is an exception in the history of trials for international crimes. The judiciary was also able to overcome the organisational difficulties of such a trial. The presiding judge ensured that the hearing was orderly, right up to the end. He also gave a great deal of space to the victims, who spoke in court for several months. Initially, only 50 or so were due to appear, but the number of victims increased as the hearings progressed. In all, 107 victims were able to testify.

In a country whose history is marked by repeated tragedies and dictatorships, the question now arises of this trial’s legacy. “When the trial opened, we thought that September 28, 2022 could be declared year zero for the end of impunity in our country. Unfortunately, the abuses continue. Opponents are disappearing. It’s quite frustrating to see that such practices continue,” laments Bah. One thing is certain, according to the lawyer: “Since the September 28 massacre has been prosecuted, it is quite possible that other cases will be too. The machine has been set in motion, and other trials will inevitably be organised.”