At the end of September 2024, two days were devoted to the testimony of Bol Maker Juol Kor. He is the 16th witness to climb the wide steps leading to the second floor of the Stockholm courthouse and to courtroom 34, where the longest trial in Swedish history has been taking place for a year now and will continue for another year and a half. There are as many more witnesses to come after him before the beginning of December. This is not counting the recorded testimonies of three witnesses to be heard at the beginning of October -- voices from beyond the grave of three plaintiffs who have died since this exceptional case began.

Among the other plaintiff witnesses who preceded him, there were former Swedish employees of Lundin Oil who were assigned to communications and told how helicopters from the Sudanese national army came to refuel at the Lundin Oil base. They include Liah Diu Gatkuoth, a former child soldier recruited to protect the oil installations, who told the Stockholm court how Lundin envoys tried to buy his silence, which triggered the opening last June of an investigation adjoining the current trial.

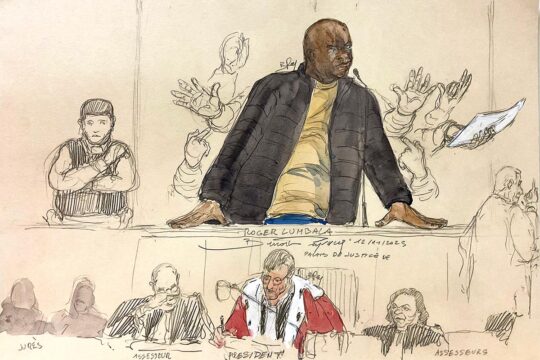

South Sudanese citizen Bol Maker Juol Kor, wearing a charcoal grey suit, arrived specially from Africa for the trial. A teenager at the time of the incident, he lived in a village not far from the road built by the Swedish oil company to access Block 5A, the extraction area. The witness remained seated in front of the presiding judge, Tomas Zander, flanked on the left by his lawyer and on the right by two Nuer-Swedish interpreters, repeating the same pattern of appearances since the plaintiffs began to appear at the end of May. The court president spoke a welcome, and pointed out that the witness was expected to give an account of what he had seen and experienced, not of what had been reported to him. Then followed questions from the prosecutor, which took up the first day, then rare questions from his lawyer, and finally the cross-examination of defence counsel for Lundin Oil chairman Ian Lundin, in the dock alongside former director Alexandre Schneiter. The two senior executives, who are pleading not guilty, are appearing as accessories to war crimes committed in southern Sudan between 1997 and 2003.

Witness after witness was subject to cross-examination, which pointed to differences between their accounts given in court in 2024 and the accounts of interrogations carried out by Swedish police officers who came to question them in Africa during the investigation. But with each witness, the voices of South Sudanese victims were heard in the Swedish courtroom as a counterpoint to a defence strategy that has focused on two areas: demolishing the credibility of NGO reports that warned of the situation in “Block 5A” where Lundin Oil was looking for oil, provoking attacks on villagers living in the area; and asserting that if there was fighting, it was the result of long-standing conflicts between clans and tribes over banal issues of stolen cattle, which existed before Lundin Oil and continued after it left South Sudan.

“The other side of the sunset”

According to the defence, Lundin Oil tried to build a better world for the local people, for example by building a road and a school. Bol Maker Juol Kor talked about this road. But first he described the attacks on the villagers. In Duar, in 1998 when an Antonov aircraft dropped barrels of oil that exploded on the ground, “they come during the day, when the sun is at its highest”. Seventeen people were left dead. The Antonov “came from the sun”. There is a lot of talk about the sun in the testimonies. So when, a few days earlier, another witness, Tomas Malual Kap, spoke through an interpreter about an area controlled by the rebels, “on the other side of the sunset”, the annoyed court president explained to him that “in Sweden, we speak of east and west”.

After each attack, Bol Maker Juol Kor recounts his frantic flight towards the forest bordering the village. “What was it like that year in Kuach?” asks prosecutor Eva-Marie Häggkvist. “Peaceful, calm?” “No,” replies Bol Maker Juol Kor, “neither peaceful nor calm”. “It was because the Arabs were fighting us. We were targets,” he continues. “The reason was that where we lived, there was oil, and they wanted to seize it, build the road through our territory to access the oil, and they didn’t want us to stay. It was the building of this road that destroyed us.”

“Could you use the road?” he was asked. “‘No, we couldn’t.” “Why not?” “We were afraid because they had killed people using it.” “Who?” “Those Arabs.”

His father and mother shot to death

He tells of the arrival of the “gunships”, low-flying helicopters that strafed. Then came ground troops and cattle rustlers. The same modus operandi was reported by other witnesses. Bol Maker Juol Kor recounts the three times he was abducted to become a soldier, when he was 16 or 17, and the three times he managed to escape. He recounts the attack in 2002, soldiers who left their lorries -- some on foot, others on horseback -- and the shooting. That day, his father and mother were shot. His father, who was shot in the back, and his mother, shot in the legs, died of wounds shortly afterwards. He fled into the forest.

“When you fled in 2002, did you use the road?” asked the prosecutor. “No, not the road, we took refuge in the forest.” “Why not take the road?” “We were scared, the military used the road.” These questions were repeated in all shapes and forms, the prosecutor trying to cement the facts with precision so that the prosecution’s case holds up, knowing that the defence will try to cast doubt by relying on details. “How far was it from the village to the forest?” “It depended. If we fled, we might spend two or three days there.” The translation sometimes seems to leave something to be desired. “We were talking about distance,” says the court president, somewhat annoyed. “How long did it take to get home from the forest?” “Nobody had a watch. But it’s not that far, we live near the forest.”

“Who wrote this report? Where does he live?”

When Ian Lundin’s lawyer began his cross-examination, he was faithful to the technique he had been using since the end of May: looking for a loophole to discredit the entire testimony. He tried to find out how many people lived in Kuach. “I can’t say, we didn’t count the people.” “But is it 100, 500, 1,000? An estimate? Maybe you can guess?” “It’s difficult for me to estimate, I was a young boy at the time.”

Above all, the lawyer confronted Bol Maker Juol Kor with the reports written by employees of the security companies who worked for Lundin. They described the situation on the ground and the benefits the road brought to local commerce. Extract after extract was chosen to show that Bol Maker Juol Kor’s testimony was not in line with the reality described in the reports, but the plaintiff caught the lawyer in his own trap.

At one point, a report mentions the road that runs through a village that the lawyer describes as that of Bol Maker Juol Kor. “This text doesn’t mention Kuach,” the South Sudanese said calmly. “It’s the road that runs through your village,” the lawyer retorted angrily. “I’d like to ask who wrote this report,” the plaintiff replied. “Where does he live? In Kuach, in Bentiu? You’ll have to be more specific.” The lawyer continued to project extracts from the Lundin Oil reports onto the four wall screens. Bol Maker Juol Kor did not give up. “It’s not right. Who wrote this report? I was there myself, nobody was using that road. Is there a video of people using this road in my village?”

During a break on the second day, Bol Maker Juol Kor told Justice Info how he felt. “All these reports written by company employees, how can they believe them?” he asked. “I can see what Lundin’s lawyers are trying to do -- to make people believe that the deaths, injuries and burnt villages are the result of tribal conflicts over stolen cattle that have nothing to do with the presence of oil.”