JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

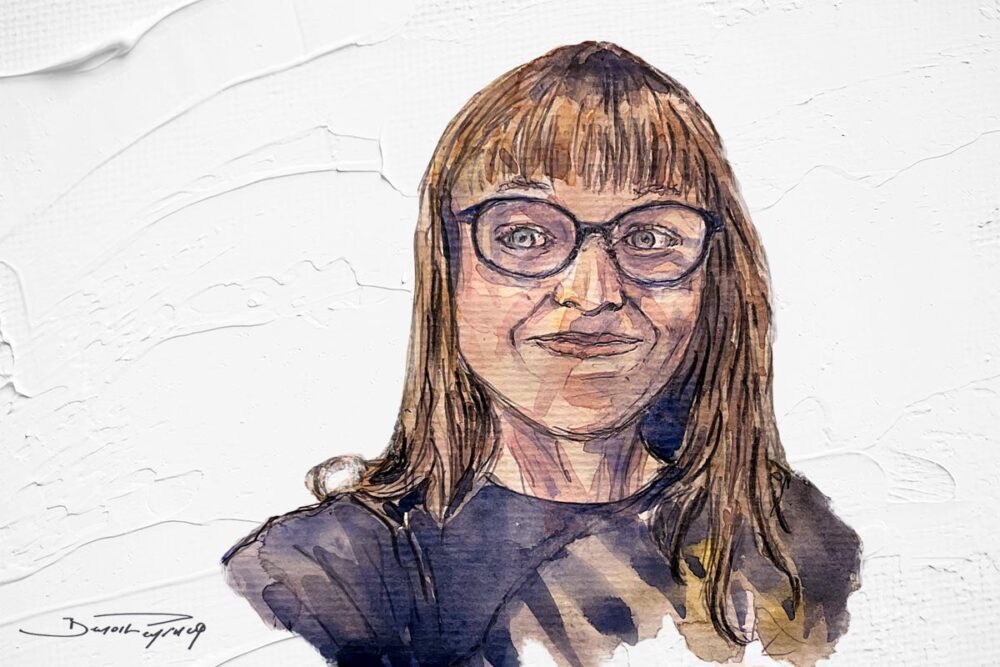

Lucy Gaynor

Historian, PhD Researcher at the University of Amsterdam and NIOD-Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies

On November 8, 1994, less than four months after the genocide in Rwanda, the United Nations created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Over the course of almost 30 years of trials, how has this court forged its account of the genocide, and how has it evolved? Historian Lucy Gaynor is completing her thesis on the role of expert witnesses in the construction of the ICTR's historical narrative. She shares reflections from her research with Justice Info, where she is a regular contributor.

JUSTICE INFO: Approximately 24 individuals that you classified as “historical expert witnesses” have appeared before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) over the course of 26 years. They testified in 22 different trials: 11 on behalf of the prosecution; 12 on behalf of the defense; and one for both. You focused on the testimonies of 5 of these historical expert witnesses. They span about 17 years and 8 of its trials. Could you first explain who and why you chose them?

LUCY GAYNOR: It’s difficult to identify a historical expert witness in the first place because most of them in fact are not historians. The five I chose from the pool were based on my interest looking at history over time. I think what’s most interesting and most unique about the ICTR is the length of time that it took, not even including the Mechanism [the judicial body that replaced the ICTR once it officially closed in 2015]. So those I chose have testified more than once over a number of years. I also wanted a range of prosecution-called and defense-called experts who testified in different kind of trials. So I have two prosecution experts, Alison Des Forges and André Guichaoua, two defense experts, Helmut Strizek and Bernard Lugan, and one who testified for both, Filip Reyntjens.

Because of the nature of these crimes, lawyers, judges, prosecutors have to turn to historical experts because it’s the only way they can understand and evaluate complex, violent, and contested facts. But of course it immediately creates a tension between narrating history and having a legal focus. How do you see that tension playing out?

I saw it as a three-way tension. It ended up being a tension between history and law and time. Historical experts are quite unique. If you call an expert in ballistic for example to testify on the use of a certain gun, I don’t think any prosecutor or judge is going to think he or she knows better. When an historical expert comes to testify there is an unspoken acknowledgment that the lawyers questioning them, and the judges, already either think they know or implicitly have an understanding of what happened. So you have this tension between history and law and as the tribunal progresses that tension changes. Sometimes in early trials everyone was happy to hear a lot of history because they wanted to use it for their own purposes. But as time went on and the history that was spoken about became more solidified, more sedimented, then everybody started to be more reluctant to look at it because – whether it is the prosecutor saying that there was a planning of a genocide, whether it is the defense arguing that there was no genocide, or whether it is judges whose only awareness is based on reading other judgements – they think: ‘I understand that now, so let’s move on’. So the tension is there from the beginning but it’s a three-way tension.

As time went on the experts who helped to construct that original history became very frustrated when they couldn’t nuance certain parts of it.

Can you tell how time impacted the historical narrative at the ICTR, the way it was constructed or the way it was contested?

There was essentially a story about Rwanda that was built up much like convictions or acquittals build up legal jurisprudence. But the narrative jurisprudence kind of happened by accident. When Akayesu [the first ICTR trial in 1997 was that of Jean-Paul Akayesu, a former Rwandan mayor] was convicted there was an understanding of Rwandan history that was then part of the tribunal. As time went on that understanding began to be taken for granted and even the experts who helped to construct that original history became very frustrated when they couldn’t nuance certain parts of it. So what you see as time passes, everybody becomes more tense and more restrained in trying to talk about history when actually what the tribunal needed was for everybody to become more nuanced in talking about history.

Do you have examples?

The first testimony of Des Forges I looked at was in Akayesu in 1997 and the last one was in Zigiranyirazo in 2005. She starts off very nuanced and very open. Then in 2002 when she testifies in the Media trial and the Bagosora trial she has such a target on her back as being the narrator of this history that she gets very defensive about it and very ingrained in her own ideas. And by the time she testifies in 2005 she talks a lot more openly about the difficulties of saying anything with 100% certainty as an historian. I don’t think she would have ever opened that ‘can of worms’, so to speak, in the Bagosora trial [Théoneste Bagosora, a former cabinet director at the Ministry of Defense, was considered as the most important accused before the ICTR] because everything was so argumentative. You go from this almost very optimistic position in terms of narrating history to a very defensive one to almost a kind of resignation to those frustrations that she’s clearly not been able to resolve within the trials.

There is so much more that goes on behind the scenes. The judgements only really tell part of the story in terms of understanding the history.

So the court at the beginning is very open to form a narrative because they don’t have any, and the experts are more concerned about having the basic narrative being written. And years later the court has a much more narrow interest in history and the experts want to be more nuanced and more complex?

Yes, and they want to be broader. If you look at just the judgements it’s a very authoritative history but you don’t really realise how much actually never made it into the judgements or the indictments because it wasn’t relevant. There is so much more that goes on behind the scenes. The judgements only really tell part of the story in terms of understanding the history.

Is it also due to the fact that the ICTR started with “minor” trials whereas in the 2000s it moved to central players where history mattered and had more relevance to the guilt or innocence of the accused?

That’s a smaller factor than I first thought. Filip Reyntjens actually says that out loud in the Bagosora trial when he turns to the judges and says: This should have been the first trial. In part he is right; in part he overestimates the ability of any one trial to set up a robust history. The less obvious part of the problem is the fact that at a tribunal like the ICTR the prosecution narrative builds as it goes on but the defense narrative primarily begins and ends in the same trial: it is more contained. Akayesu’s counsels, at the end of the day, all they’re really trying to do is to make sure Akayesu is acquitted on specific counts of violence in Taba commune. Had the Bagosora trial been first I think you would have had a similar problem. You would still have that difference between the prosecution having all their time to build a narrative and the defense having only their individual trial to focus on.

The whole trial process is so interactive that nobody has real control over the narrative that emerges. Everything is so dependent on what kind of questions are asked, what mood the expert is in, how interested the judges are in engaging with the expert.

The Bagosora judgement stands out as an attempt to have the most nuanced, complex narrative that the ICTR ever allowed, including on the sensitive subject of the planning of the genocide. Yet it never served as the new narrative, the new reference. Nobody remembers it. And it was immediately erased by the appeals chamber. It’s as if it can’t become a dominant narrative…

I think what’s most frustrating about that is that it’s difficult to pinpoint what could be done differently. What my research has shown to me is just how the whole trial process is so interactive that nobody has real control over the narrative that emerges. Everything is so dependent on what kind of questions are asked, what mood the expert is in, how interested the judges are in engaging with the expert. I don’t know if the Bagosora judgement had been the first judgement whether it would have had a different impact.

Four of my five experts testified in the Bagosora trial – Des Forges, Reyntjens, Strizek and Lugan. All four were more assertive about their narrative than they had been in the earlier trials. Des Forges was the most assertive: here is the evidence of the planning and here is my interpretation of the evidence. And yet the judges were nuanced on it, which they may not have been earlier on. So I am not sure if there is a correct order to do these trials.

The experts themselves, I think without really intending to, almost set it up that they were some of the only ones that could really explain what was really meant.

Three experts were of particular importance: Des Forges, Reyntjens, and Guichaoua. You say that they had formed a kind of informal historical consultancy team for the ICTR’s office of the prosecutor even before the Tribunal’s first trial had begun. How did they shape the prosecution narrative and for how long?

My opinion is that they shaped it all the way through. Even when the prosecution faced challenges such as the acquittal on conspiracy to commit genocide [the narrative] was very much built from the same starting point every time. What was so specific to the Rwanda context was the insistence by all the experts that there was always another layer of interpretation compared to what originally appeared obvious. Des Forges called it double language, Guichaoua called it double speak. The experts themselves, I think without really intending to, almost set it up that they were some of the only ones that could really explain what was really meant. If I tell you about the history of a country and tell you that politicians always said one thing but meant something different and you can only understand that if you understand the context, then of course you as a prosecutor are going to come to someone you think understands the context. The nature of Rwandan history meant that the prosecution could become more dependent on historical experts, compared for example to the Yugoslavia Tribunal where history was much more forensic, about political movements, the formation of political parties and political speeches. In Rwanda it was about those things but it was about understanding what they ‘really meant’ when they said or did these things – and that allowed the experts to have a huge influence on the prosecution narrative.

At least two of them, Des Forges and Guichaoua were almost embedded in the Office of the Prosecutor. They played a role in the investigations on top of being called as expert witnesses. Could you see them dealing with the tension of serving historical truth and serving the tribunal’s goals?

I saw it in two ways. One was in a very existential way that I can imagine was difficult for them. And the other you even see it in the banalities of the court. For example in the Government II trial, the prosecution asks whether they can get a ruling from the judges that it’s okay for Des Forges to talk to members of other prosecution teams, because she was involved in so many trials at the time. The defense had multiple objections to this and the discussion goes on for multiple pages of testimony where at some point the judges are considering who Des Forges can or cannot have dinner with while she’s in Arusha. It ends with everyone almost laughing at the insanity of it.

Des Forges is very clearly struggling with the fact that part of her work involves being actively pursuing justice while her academic work seeks to narrate the atrocities that led to that justice in a more objective way.

In the Zigiranyirazo trial even the judges acknowledge this tension between historical truth and serving the tribunal. They acknowledge the defense’s two-fold objection to Des Forges as an expert: one, is her expertise to be relevant; and two, is that even if it is relevant is she so embedded in the office of the prosecutor that her evidence is irrevocably tainted. In that cross-examination Des Forges describes herself as a resource person for truth and justice. She is very clearly struggling with the fact that part of her work involves being actively pursuing justice while her academic work seeks to narrate the atrocities that led to that justice in a more objective way.

You also have the experts trying to walk a tight rope. Des Forges is asked multiple times questions about the word genocide or about the existence of a war and she says: I’m not a lawyer. Guichaoua regularly says: I’m not an historian.

As the trials progress it’s quite clear that in fact they’re only there to give the answers that the questioning counsel want them to give.

Des Forges died in a plane crash in 2009; Reyntjens was no longer called early on because of his critical political views on the Rwandan government after the genocide; Guichaoua stayed until the end but was often in conflict with the Office of the Prosecutor. Did you see the evolution of their relationship with a court that they initially wanted and supported and that gradually seemed to push them aside?

I think so. Even before they are pushed aside you could see a frustration with the lack of space that they have to actually take control of any sort of narrative, their decreasing agency as active participants. As the trials progress it’s quite clear that in fact they’re only there to give the answers that the questioning counsel want them to give. When Reyntjens testifies for the defense in the Butare trial, the prosecutor doesn’t ask him a single question in cross-examination. One would assume that that’s the dream: you’re facing a witness you used to know very well and who has now changed his mind. The fact that the prosecutor didn’t ask him any question to me shows the attitude towards the experts as using them for a specific purpose and that’s it.

You describe a shrinking of the space that tribunal actors – counsel, judges, and experts alike – allowed for uncertainty or nuance, while scholarly knowledge about the genocide had grown. Do you see the historical narrative following a linear evolution, or did it follow a fluctuating path?

It completely fluctuates, and that’s what is so difficult to understand about the ICTR. You have this very authoritative narrative that emerges in each judgement. That narrative is solidified, almost sedimented. But actually the foundations of that narrative are so fragile, so contested, so dependent on so many different factors. I went into the research thinking: Okay, there is a simplistic narrative at the beginning and by the time you reach the Bagosora judgement it is more nuanced. It’s so much more complicated than that because it is so unpredictable.

There are probably different groups or audiences to the ICTR and each took out one narrative from it. Each of these groups have a different understanding of how the ICTR dealt with history.

And eventually is there one narrative that everybody agrees is the one that came out of the ICTR?

I think there are probably different groups or audiences to the ICTR and that each took out one narrative from it. There is quite a clear international justice community narrative about not just the validity of the verdicts but an overarching understanding of what happened in Rwanda in 1994. You have a Rwandan interpretation of what happened in 1994. And you also have a potential interpretation that tries to bring complexity, and sometimes borders on denialism. Each of these groups have a different understanding of how the ICTR dealt with history. And potentially all of them have fuel for that fire. All of them could point to things that happened in trials and say this and that was discussed.

There is much more nuance within the actual trials. The problem is the disconnect between how complex the trial is and how sanitized the judgement is. That’s where you get the disconnect between how people understand history.

You end up with this: yes, we agree with the experts that there was planning, we agree that it was some time before 1994, but we don’t necessarily know which of them is right about when it started, how it started, and who started it.

Let’s take the example of what is still so controversial and contested: the question of the planning of the genocide. There are those who say that of course it was planned and it had to be planned otherwise you may have a problem qualifying it as genocide. There are others who say it wasn’t planned, some of them wishing to conclude that therefore it wasn’t genocide. And others who say: it’s not the point, it’s a singular history with its specific dynamics that don’t have to be understood through the lens of Nazism. Did you identify the meta narrative of the ICTR on the planning of the genocide?

When you combine the historical narrative and the legal narrative of the ICTR you end up with a “Schrödinger genocide” [according to an experiment imagined by Schrödinger, two realities apparently incompatible can superimpose]: we have a genocide, it was planned, but not in the way or by the people we thought it was planned by. To me that is one of the most complicated aspects of the planning. Even the judgement in the Bagosora trial talks about this: prosecution experts all say it was planned but then they all give different dates from which the planning began. Des Forges says genocide was planned from late 1993 onwards; Reyntjens is more skeptical, he says it wasn’t planning, it was more incremental and it started from 1990. Then he says that if he had to give a date he would say 1992. You have two different experts giving three different dates for the starting of planning, which I think is perfectly feasible if you think in terms of meta narratives of history. But when you try to superimpose those on the legal imperative of finding intent to convict someone of a crime, they can’t work with that. And you end up with this: yes, we agree with the experts that there was planning, we agree that it was some time before 1994, but we don’t necessarily know which of them is right about when it started, how it started, and who started it.

Did you feel the court was frustrated about it?

I think this is one of the reasons judges don’t like historians. Because historians usually would say things like: ‘oh, it could have been 1990, or 1992’. But the law doesn’t want that. The law has a function that doesn’t need or want that. By the time you have the Bagosora trial, everyone is quite aware of the complexity of it. Chile Eboe-Osuji [the prosecutor in charge of the Bagosora trial] opened the trial with the most dramatic introduction of the plan. He comes up with this really complicated document that’s called “the tangled web of conspiracy” that he shows the whole court. Then he quotes Shakespeare and the quote he uses is: ‘Oh the tangled web we weave/When first we seek (sic) to deceive’. Which is actually not a quote from Shakespeare but from a poem by Scottish historian Walter Scott. To me that sums everything up: you try to show this Shakespearian, almost medieval conspiracy for genocide and actually it’s something completely different. It doesn’t mean it’s not a conspiracy, it’s just different.

And the narrative he offered in what was arguably the most important trial at the ICTR was very much dismantled in the judgement. It didn’t stand the test of facts and evidence.

It didn’t. And you can see the frustration in his interactions with Des Forges in that trial. There were so many defense objections at the start of that trial that there was one day where Des Forges didn’t even speak. She almost became an observer at her own testimony. The only time she spoke when was Judge Lloyd Williams asked her: ‘how long are you around for’, and she was obviously quite frustrated. Eboe-Osuji started to try and gallop through his narrative and Des Forges was really distressed at trying to have the narrative simplified, even when it was a ‘friendly’ prosecutor. He’s trying to move on because he has a legal goal in mind and she’s taking 3 or 4 minutes to argue with him over trying to assert the historical importance of details. That to me sums up the tension.

It’s difficult for the actual quality of a defense expert’s interpretations to be assessed.

How do you compare the role of historical experts who testified for the prosecution and those for the defense? Did they have a different role?

Yes. I think the defense experts’ role, regardless of the expert, is a lot more difficult than I first realised. These defense experts are called – especially for Lugan and Strizek – with the primary function to debunk Des Forges. Strizek is not here to talk about his view of the Rwandan genocide, he’s here to talk about Des Forges’ view. And she is not there. So he’s having a kind of disjointed conversation with Des Forges through the questions of the defense and the prosecutor. It’s difficult then for the actual quality of a defense expert’s interpretations to be assessed.

I spoke to a defence lawyer in one of the thematic trials and told him I was interested in the role of historical experts – I don’t think he knew I was an historian. And his response was: ‘What’s a historical expert? There’s no such thing!’. He had no interest in historical expertise; he had an interest in the role that the expert could play in debunking the prosecution. It’s a completely different strategy but it’s also extremely difficult for the expert. They have to be an expert on history and an expert on the expert.

There is this idea that these experts are unimpeachable because they’re from abroad. But you’re unimpeachable to who?

All the experts you look at were not Rwandans. The whole narrative is shaped by outsiders. Any comment on this?

What you see with international tribunals as a whole is that often scholars – especially from the Global North – will say that the more distant an expert is the better. There is this idea that these experts are unimpeachable because they’re from abroad. But you’re unimpeachable to who? To the people who are listening – who at the ICTR were also non-Rwandans. The purpose of the expert is to narrate history to a very small subset of people – the judges – who then write judgements that are to be taken as the history of Rwanda, or of the genocide at least, and everyone is going to agree with that. If we assume that that’s the aim, then the whole enterprise is doomed from the beginning. Because you just have to acknowledge this disjunction. Acknowledging the distance that exists between who’s narrating the history, who’s listening and who’s writing it, and who has to receive that history. These are potentially four completely different groups of people. This is not necessarily something that changes the way the tribunal works but it changes the way we now view how successful or unsuccessful the tribunal was, because depending on who you ask, the tribunal either did a very good job with history or a very terrible job, and there is very little in between.

Do you see the same dynamics playing out when it comes to historical narratives before domestic courts using universal jurisdiction, like for Rwandans being tried before a French or a Belgian court, a Liberian before a Swiss court, or a Syrian before a German court?

I think it differs even within universal jurisdiction by the legal system. And that sums up how dependent these narratives are on the interactions in the courtroom. It has happened in The Netherlands that the judges have asked for a lecture on history before a trial, separated from it, because it’s not necessarily deemed as relevant to the individual charges but deemed as useful for the judges to put the charges into context.

The ICTR, even when it said it didn’t want to write the history of Rwanda, went on for so long and tried so many people that it ends up taking up that role. In universal jurisdiction trials there isn’t this expectation.

Which in another legal system would be considered as a basis to dismiss the judges for being tainted...

I would think so, or at least the expert who gave the lecture would be challenged for his or her biases or interpretations. In terms of universal jurisdiction, it is so sporadic and so spread out that you don’t have the same pressure on lawyers or judges or experts to write this narrative. It’s a lot easier because it doesn’t necessarily come with the same kind of historical baggage as these big tribunals that set themselves up to perform all these different functions. The ICTR, even when it said it didn’t want to write the history of Rwanda, went on for so long and tried so many people that it ends up taking up that role. In universal jurisdiction trials there isn’t this expectation.

Did you come up with a conclusion on the use or not of historians or historical experts in atrocity trials? Should we not have them or do we have to come to terms with the inherent ambiguities and contradictions that you’ve just exposed?

I have fluctuated a lot. For a long time my personal response was that I found these experts very important… and that I wouldn’t do it in a million years. But if I wouldn’t do it then somebody else would if they were asked. I would be interested in how many experts said no before the experts that ended up testifying said yes. The conclusion I have come to is that a more holistic approach is for everybody involved, not just the lawyers, to be more aware of the fact that none of them have control over what narrative emerges from the courtroom, and therefore to be more okay with the nuances, the challenges, the uncertainties that are going to emerge in a historical expert’s testimony. They are so unavoidable that unless you could come to terms with them it’s going to completely undermine the history that you’re trying to write.

Robert Donia, who testified multiple times at the UN Tribunal for former Yugoslavia in the same way Des Forges did at the ICTR, always said that the most valuable words an expert witness could say would be: I don’t know. But often when an expert says ‘I don’t know’ they’re quite aware that somebody will attempt to undermine everything else that they’ll say on the basis that they don’t know this one thing. So what I’ve really observed from the trials is that it is more important for experts to be less defensive about their expertise – I say this confidently sitting in a room where there is no one cross-examining me in front of five accused and ten lawyers…

There has to be this understanding that when history is brought into this adversarial system it is distorted

It is also the adversarial system that allows for this defensiveness because it is an inherently hostile exercise in a way that a more inquisitorial system is not. It allows for so much competition that it is a zero-sum game, when actually ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I was wrong’ are two different things. Perhaps judges can also learn from that: there has to be this understanding that when history is brought into this adversarial system it is distorted in a way that anyone reading it has to take into account when they have to process what’s usable and what is not.

Eventually, is there a coherent historical narrative that came out of almost three decades of ICTR trials?

I am smiling because this is why lawyers hate historians: my answer is that it depends on what question you ask. The problem for a tribunal to be a resource for history is that the tribunal has such authority that using it as a resource inevitably means that you’re either pushed into arguing in favour of, or against it. And then you’re entrapped by the adversarial system because you’re thinking about the narrative and your instinct is to say: was it right or was it wrong? It’s just as easy when using it as resource to being dragged into the zero-sum game that the adversarial legal system is. And of course there isn’t just one historical narrative, there may be fifty different narratives for each accused, for each year after 1990.

Lucy J. Gaynor is a PhD Researcher at the University of Amsterdam and NIOD-Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies. Her PhD, tentatively titled ‘The Past is Never Dead: Historical Narratives in International Criminal Trials’, examines the narration of history by expert witnesses within international courtrooms. Using the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda as a case study, the project takes a sample of 5 experts, and 8 trials, to reflect upon the impact of the passage of time upon law and history’s joint co-operative and contested attempts to narrate the mass atrocities which took place in Rwanda in 1994.