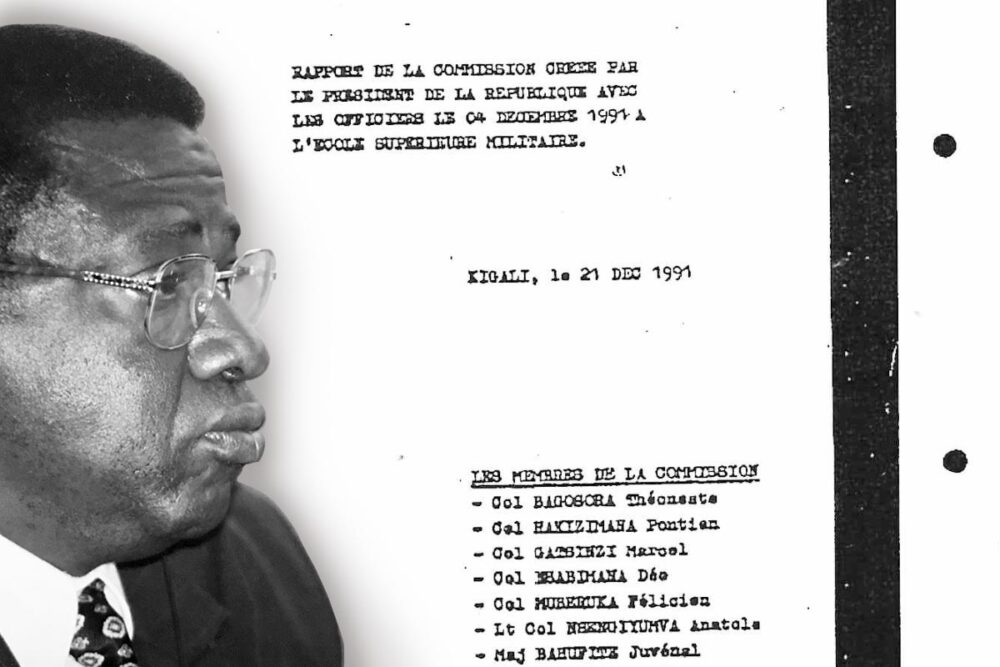

The civil war in Rwanda had been waged by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) for fourteen months when, on 4 December 1991, President Juvénal Habyarimana set up a commission to advise him on what needed to be done "to vanquish the enemy at a military, media and political level". A group of senior officers was assembled to take stock of the situation and come up with recommendations. Among its ten members, the most senior officer was Colonel Théoneste Bagosora. He chaired the commission. On December 21, they submitted their report to the head of State.

The report was never made public, except for its most sulphurous extract on the definition of the enemy. This extract was to become a key piece of evidence in proving the planning of the Tutsi genocide that took place just over two years later, from April to July 1994, the day after Habyarimana's assassination. This genocide, in which a large part of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) took part, turned Bagosora, director of cabinet at the Ministry of Defence in April 1994, into the prime suspect.

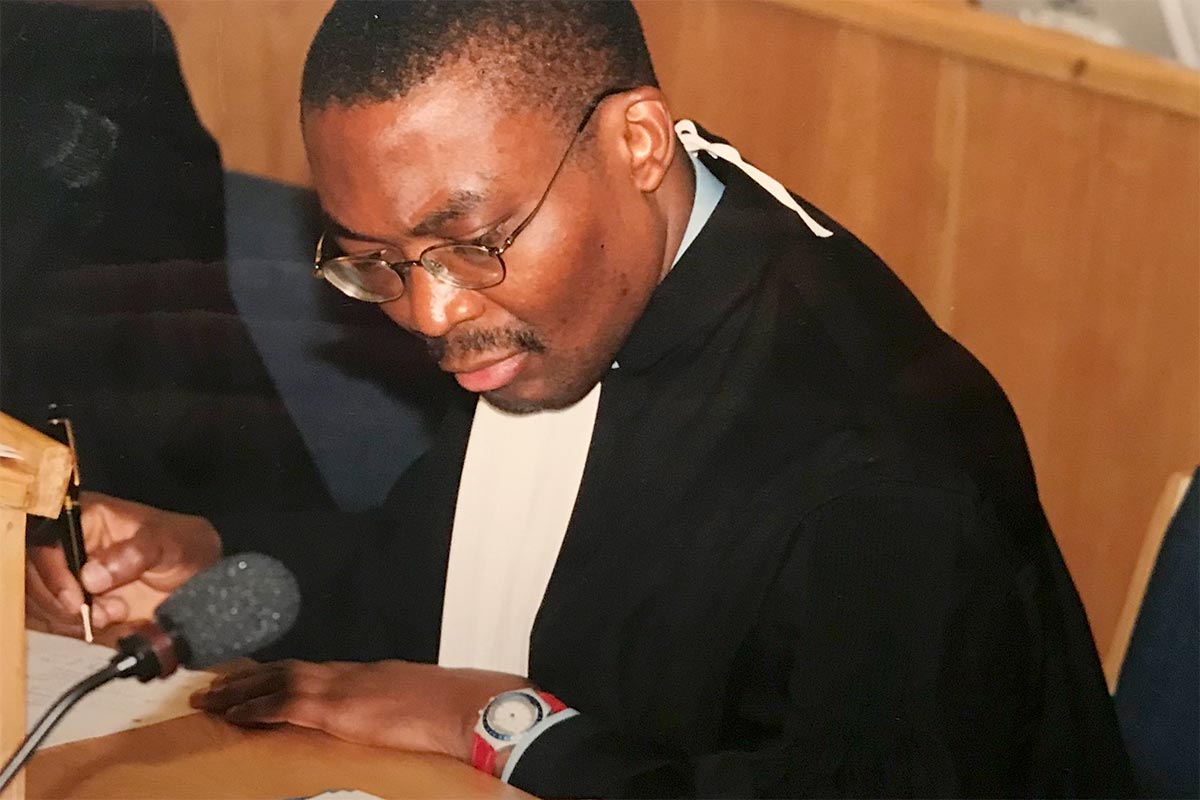

At the opening of the trial of Bagosora and of three other former FAR officers in April 2002 before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), set up by the UN on 8 November 1994, the prosecutor, Chile Eboe-Osuji, defined the 1991 Commission's report as the birth certificate of the genocidal plan. Before him, the judges in the first ICTR trial against a former mayor, Jean-Paul Akayesu, had referred to the extract to demonstrate the genocidal intent.

The Bagosora judges' nuanced judgement

Except that neither the prosecutor nor the judges had the full report. Officially, it no longer existed. All they had was the famous extract entitled "Definition and Identification of the Enemy". This is the second part of a six-part report. It is also the most disturbing part of the report.

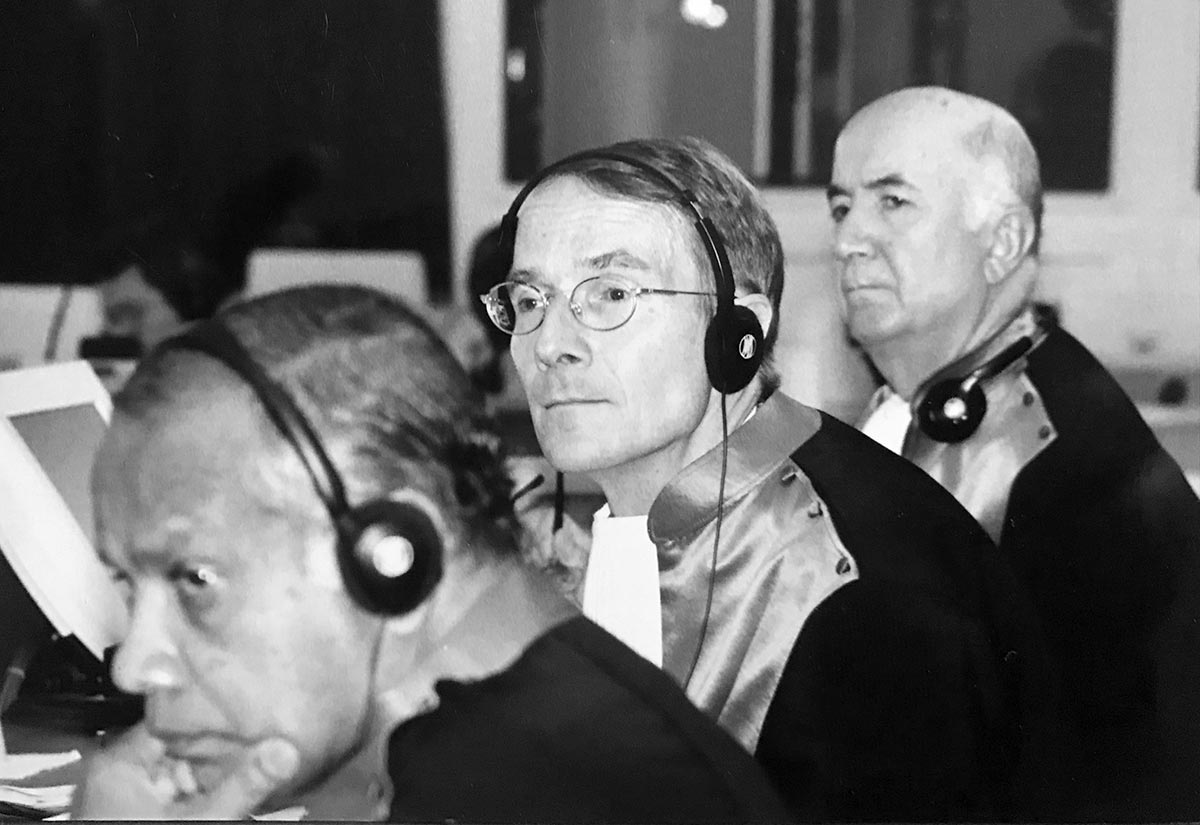

On 18 December 2008, the ICTR Trial chamber handed down its judgement in the Bagosora case, sentencing him to life imprisonment for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. His sentence was reduced to 35 years in prison by the Appeals chamber. Bagosora died in 2021 in a UN prison in Mali. However, the 2008 judgement clearly stands out as the ICTR's most nuanced and complex judgement in its analysis of the planning of the genocide. The judges respond to the prosecutor's analysis of the extract from the 1991 Commission's report.

"It is clear that the definition of the ‘enemy’ contains both an ethnic component and a reference to proscribed acts," the judges noted, pointing out the dangerous ambiguity of the document. For example, "the word ‘Tutsi’ is used 14 times in the document, and interchangeably in some places with ‘enemy’, and there are generalisations which may indicate that the Tutsis were unified behind the single ideology of Tutsi hegemony". Consequently, "it may be asked whether the way the ENI document [the extract in question] is formulated, combining both ethnicity with more direct language about the RPF, is an example of ‘double language’, the real intention of its members being to target the Tutsis", explained the judges.

For the prosecutor, the case was clear: this extract was "a step towards a criminal conspiracy". The judges, on the other hand, dismissed such an interpretation. They were more concerned with the context in which the events occured. First, they noted that defining the enemy is common practice in the military, in Rwanda and elsewhere. Consequently, the commission "was not in itself unusual or illegitimate, in particular in view of the fact that there had been hostilities on Rwandan territory since the RPF invasion on 1 October 1990".

"Read in context, the Chamber does not agree with the Prosecution that the definition implies that all Tutsis are extremists wanting to regain power," wrote the judges. The content may be disturbing therefore, but it does not demonstrate criminal intent. The judges were also aware, in 2008, that three or four of the members of this commission were among the few reputed senior officers of the FAR who had opposed the genocide in 1994. Even though no testimony had ever been taken from them in a specific and public manner by the ICTR prosecutor's office.

Justice has been served, history remains

"It is not contended that the accused agreed at the same time on a plan, or that this plan consisted of a single, unified course of action, with an equal sharing of tasks," explain the judges. "Instead, the correct inference to be drawn from the evidence is that, at different times, each of the accused agreed to participate in a broader and longer effort to increasingly homogenise the Rwandan society in favour of Hutu citizens, with the object of killing Tutsis if necessary. It is their participation in this process - and their willingness to create or exploit various opportunities to accomplish it - that characterises their agreement."

The judicial significance of this report, considered as being so decisive at the time, has now lapsed. The ICTR trials are over. But its historical contribution remains. As part of its work on the ICTR trials, Justice Info has obtained a copy of this report, which was believed to be lost. It belonged to the accused. Some of the pages are unfortunately difficult to decipher, but the essence is there. To mark the 30th anniversary of the creation of the ICTR on November 8, 1994, we are placing the copy in the public domain. Everyone will now be able to carry out a more complete and contextualised analysis of this document which, in the eyes of the ICTR prosecutor, was to forge the story of the planning of the genocide of the Tutsis. Before the judges told him that it wasn't that simple.