On November 13, Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) unveiled its seventh indictment against members of the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the second against that rebel group’s leadership.

In its first indictment in the macro-case on child recruitment, the Acknowledgement Chamber of the special tribunal stemming from the 2016 peace agreement determined that the use of children under age 15 occurred in “all structures and in a sustained manner over time”. For this reason, it charged six of the seven members of the FARC’s last Secretariat – all except Rodrigo Granda – with the war crime of conscripting children under the age of 15.

“The conscription and use of children by the former FARC was neither a sporadic, isolated or exceptional phenomenon,” said Justice Lily Rueda, who led the investigation, contradicting the version defended by former rebel leaders like Rodrigo Londoño, better known as 'Timochenko' and one of the indictees, that it occurred “for exceptional reasons”. “Despite the fact that the enlisting of children under 15 years of age was formally prohibited within the group, it did happen and it did so with such magnitude and scope that it configures a macro-criminal pattern,” Rueda added.

In its look at the phenomenon of ‘child soldiers,’ which was historically a less visible crime to Colombians than kidnapping, the JEP went beyond the presence of minors within the guerrilla. After documenting hundreds of other crimes that these boys and especially girls suffered within its ranks, the Colombian transitional justice’s judicial arm also charged them with the war crimes of rape, sexual slavery, outrages upon personal dignity, torture, homicide, as well as sentences and executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court. It also charged them with the war crime of conscripting, enlisting or using persons aged 15 to 17, which the Chamber considered feasible under customary law.

The JEP exposes FARC's contradictions

For years, the most visible former guerrilla leaders argued that the use of child combatants “was not a permanent practice” and that “one entered FARC consciously”. Throughout 759 pages, Justice Rueda meticulously contrasts these arguments of former FARC leaders with victims’ accounts, testimonies of hundreds of former rebels and even written reports from their own unit, in an eloquently narrated indictment despite its haunting anecdotes and the need to swap victims’ names for numbers over security concerns.

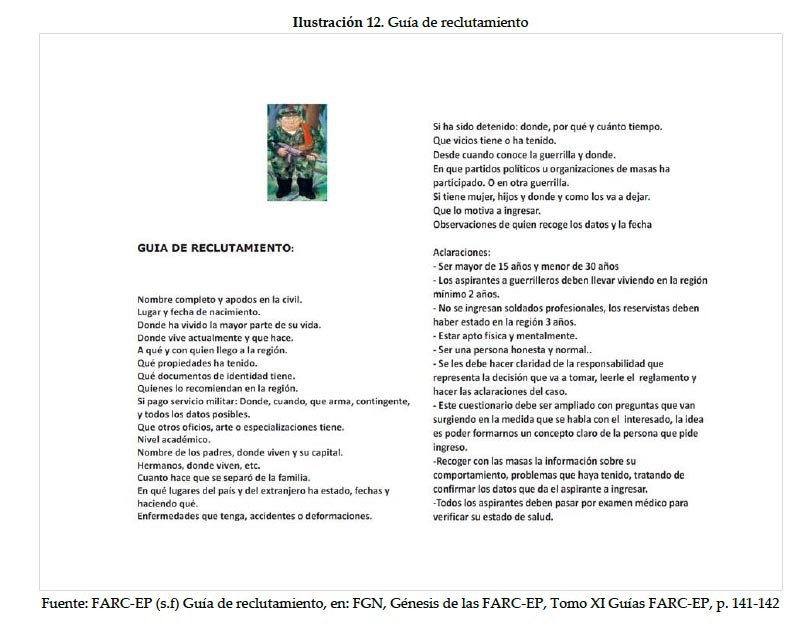

One of FARC's defence arguments was that its internal regulations prohibited enlisting children under the age of 15. A recruitment guide found by the Attorney General's Office identifies a dozen rules that recruiters had to follow, including that new members had to be "older than 15 and younger than 30," be local inhabitants, and have both physical and mental aptitude. That undated guide, headed by a painting by Fernando Botero of historic FARC leader 'Manuel Marulanda Vélez' or 'Tirofijo', also instructed them to verify "what identity documents they have".

In real life, however, these requirements weren’t met. The JEP documented 518 cases of children recruited before 15, some as young as eight. In the context of the FARC's expansion plans and the subsequent intensification of hostilities with Colombian security forces, the guerrilla ended up favouring swelling its ranks over following its own rules. It was more important for a person to be known locally (due to their fear of being infiltrated by the Army) or to be physically fit for rebel life. As one victim narrates, a rebel commander recruited her aged 12 because she “already had a body”.

These facts underscore, according to the JEP, that there was a FARC “policy of enlisting personnel that, de facto, gave more weight to the appearance of suitability to serve the rebel cause and armed action over the age of those admitted”. And it adds, “not only was there no effective mechanism to verify age, but they weren’t interested in establishing one”.

“Not only not sanctioned, but downplayed”

This wasn’t the only contradiction the JEP found between FARC and its victims’ accounts. For example, commanders argued that children received “non-military training” and tasks appropriate to their age, such as, in the words of indictee 'Joaquín Gómez,' "peeling potatoes and children's things," something all the victims denied. Yet they received military training even from age nine and also participated in war activities such as combats, installing landmines or gathering intelligence, in conditions – in the JEP’s words – “incompatible with their physical and mental maturity”.

Despite the fact that violating recruitment rules was deemed a first instance serious offense in FARC’s internal regulations and entailed an educational sanction, the JEP found that "not only was it not sanctioned, but acted upon in such a way that it went unnoticed or was downplayed". This was corroborated by victims, but also by written sources such as the Eastern Bloc’s infractions dossier, which showed sanctions against 2,967 rebels, but only nine for this type of misconduct. Members of the Secretariat were aware of this, as evidenced by a story confirmed by indictee Jaime Parra. When historic FARC leader 'Mono Jojoy' visited a camp in San Vicente del Caguán and saw the number of enlisted children, he remarked that there were many “calves” and it looked like “a nursery”. His decision to hand out baby bottles to those in charge of the unit was interpreted more as a joke than a reprimand.

Forced entry, impossible exit

Despite the theoretical rule that all FARC enlistings should be voluntary, the JEP found that more than half of accredited victims were recruited through threats or other forms of violence, including being taken from homes or schools, demands that families contribute "quotas" to the revolution, and after their recruiters got them drunk. A third were recruited through deception, including offers of non-existent salaried work, promises of reunification with family members or access to education and health care. A 14-year-old boy who contracted Leishmaniasis in his ear was forcibly recruited after arriving at a FARC camp to receive promised medical treatment.

Only one-sixth of victims arrived through persuasion, although even in many of these cases the JEP documented that prior intelligence work allowed recruiters to manipulate them by using information about adverse family or economic situations and offering them what the indictment called “mirages of paternity”. No victims recognized the term “refugees” that FARC’s top brass used to refer to minors who voluntarily came under their guardianship.

Likewise, the JEP demonstrates that leaving rebel ranks was not only not an option, as many former FARC leaders argued, but almost impossible. "You join today and until we triumph or until you die," according to one former member. Testimonies collected by the JEP confirm that 94% of the victims remained in their ranks for more than a year, amid punishments for defection as severe as torture, being tied up for two months or even being executed.

Something similar applied to life within the group, which indictee Julián Gallo described as a “conscious discipline,” but which the JEP called an “environment of permanent coercion”. Being used as human shields, having family contact forbidden and being forced to drink the blood of wounded colleagues generated, the JEP argues, emotional withdrawal, permanent fear and on at least one occasion the suicide of a girl.

“De facto prohibition of parenthood at all costs”

One of the most interesting aspects of the indictment is its focus on types of violence against girls within the FARC, beginning with those seeking to “prohibit de facto the exercise of maternity and paternity at all costs” in order to keep the troops intact and avoid security risks. The most widespread reproductive violences were forced contraception (experienced by one out of four accredited girls) and forced abortions (experienced by one out of five).

As part of this “formal policy of contraception or birth control”, explicit since FARC’s 1993 national conference, girls were subjected to injections, subdermal implants or intrauterine devices from an early age and even before starting their sex life. These decisions were made without medical assessments, information and in many cases basic hygienic conditions. Although the JEP acknowledges views like former leader Victoria Sandino’s that contraception represented freedom to decide about her body, the special tribunal points out that for the vast majority of conscripted girls it was neither a free or informed choice.

Recurrent use of these drugs had health effects, including severe pain, bleeding, infections and alterations of the menstrual cycle. One victim was left with cysts and an ovarian tumour that had to be removed. When cysts were later found in her breasts, she took advantage of an outing when they were to be amputated to defect. Another woman who was given contraceptives since age 12 hasn’t been able to become pregnant after a decade of trying, and another has had several pregnancies because no planning method works for her anymore.

This reality experienced by girls and women contrasted with that of men, who were never persuaded to use condoms or have vasectomies even though these methods had no adverse effects, since FARC considered this could affect their virility. These burdens, the JEP argues, “fell mainly and disproportionately on the bodies and lives of girls,” which made it clear that “the well-being of men in the ranks took precedence over that of women”.

“Knowledge of effects wasn’t reflected in decisions to avoid them”

According to the JEP, “an orientation to terminate pregnancies whenever they occurred was [also] tacitly derived” from that contraception policy and in at least one case a FARC unit explicitly instructed that “in case of pregnancy, curettage is mandatory”. The JEP documented cases of abortions performed against girls' will, including under threat of court martial (which could result in firing squads), held by others, and with abortifacients hidden in food or as pain pills. One victim recounts having experienced four forced abortions, all between the fourth and fifth month of pregnancy.

These abortions went hand in hand with other abuses. Although indictee 'Joaquín Gómez' insisted that women who had abortions were given leave, the JEP gave credibility to victims who said they were forced to work the following day, without rest or special care. In one particularly cruel case, the indictment recounts how an 18-year-old woman was forced, right after a forced late abortion, to breastfeed the new-born baby of kidnapping victim, Clara Rojas, who was held captive for nearly six years and separated from her child for three. Finally, the JEP identified cases of new-borns killed or forcibly handed over to others to be raised.

In all of these cases, the JEP found that FARC’s Secretariat was negligent. In its words, commanders’ “knowledge of the effects caused by contraception was not reflected in organizational decisions aimed at avoiding them”.

Tacitly accepted sexual violence

According to the JEP, one in three women conscripted as children suffered sexual violence, from rape and sexual slavery to forced unions and nudity. In its view, although it didn’t find a formal or de facto policy to promote it, “the magnitude and extent of these practices was such that they came to be understood as tacitly accepted”.

Even though two indictees, Jaime Parra and Julián Gallo, said that some reports of sexual aggressions were “armed information” seeking to stigmatize them, Justice Rueda found that at least 88 girls and one boy were forced to have sex without their consent and that even an eight-year-old girl was groped. One victim narrated a raffle among ten rebels in which whoever drew the winning number could sleep with one of them. These events left lasting consequences: one victim recounted that she had a miscarriage because a sexually transmitted infection contracted as a child within FARC’s ranks was transmitted inside her womb.

This reality was enabled by what the JEP called a “practice of non-punishment”. Despite the fact that rape was deemed a crime within FARC and contemplated the most severe sanctions, these were very rarely administered. “The absence of prevention, control and sanction measures (...) led to these actions becoming a normalized practice,” the indictment says. The mere denunciation could be dangerous for victims. One told how she was forced by her commanders, including indictee Pastor Alape, to dance with her aggressor so as not to damage the atmosphere within the ranks.

Something similar happened to a dozen victims of diverse sexual or gender orientation, who lived in the tortuous limbo of serving in an armed organization with a “de facto policy of prohibiting membership” of LGBTI people but being unable to defect. Since rebels associated homosexuality with infiltration from the army, they faced an even greater risk of being executed.

FARC’s early but half-hearted acknowledgement

Three years ago, when the JEP charged them with kidnapping, members of FARC’s Secretariat took three months to announce that they accepted the accusation. This time they opted for an early start: although it’s not yet their formal legal response, a couple of hours after the JEP's announcement, the six former guerrilla leaders published a communiqué in which they admit the conscription of children. “These events should not have happened,” they wrote.

If they maintain this view, the six would remain within the restorative lane of Colombia's two-track transitional justice system, which contemplates – if they provide truth and redress victims – 5-to-8-year sentences in a non-prison setting, as opposed to the adversarial track where, if found guilty, they’d face up to 20 years in prison. One of them, Pablo Catatumbo, has also acknowledged his role in a third indictment, in the Nariño regional case.

However, their letter also came with a warning. In it they lamented that, in their view, the JEP’s justices “have spent an excessive amount of time and resources investigating events whose occurrence we have admitted since the peace negotiation” – something at odds with their past reluctance to admit child conscription, its forced nature, and sexual violence.

Meanwhile, the first JEP indictment on child recruitment seems to be filling historical gaps. “Without anticipating what is to come, the indictment feels like a balm to us because it acknowledges what this phenomenon has meant for Colombia: the violence and rights violations within their ranks, the suffering of families still searching for children whose whereabouts are unknown, and the conscription of children under 15, which was such a contested issue by defendants since the negotiation,” says Hilda Molano of Coalico, a network of seven organizations that work with children in conflict and that has insisted on documenting these facets of recruitment that until now were not very visible.

In her words, "all this is no longer in question".