On 28 November 2024, Liberians woke up to the news of the death of senator Prince Y. Johnson, one of Liberia’s most feared and charismatic warlords. His passing away at the age of 72 in a hospital in a suburb of Monrovia, Liberia’s capital city, may signal an end to warlord politics, but his wartime legacy looms large, even in death. Until now, the prewar generation has been traumatised by his wartime exploits, while the post-war generation has been often mesmerised by his seductive post-war politics. Altogether, Johnson has earned himself a controversial spot in the collective memory. To some, he’s viewed as a hero and an ethno-nationalist, while to others he was a sadistic perpetrator of casual violence, a war criminal and the search for civil war era accountability would have been incomplete without his culpability.

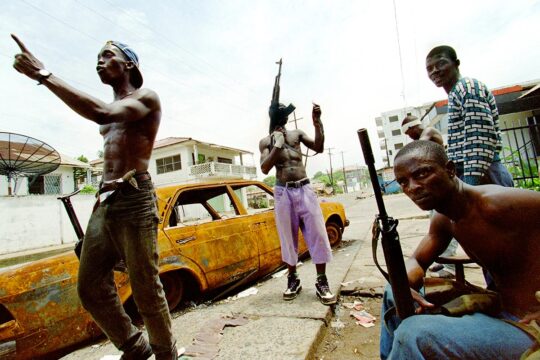

In reaction to the news of his death, Liberians on both ends of the spectrum wasted no time in taking to social media to express their deep emotions, one of respect, love and hate: “A true legend is gone to rest,” someone wrote. Another said “go and meet my mother that you sent before you”. in his defence, another wrote that if the killing of Samuel K. Doe is Prince Johnson’s only fault, then he had no fault. Doe was Liberia’s first so-called indigenous president whose politics in the 1980s led to ethnic antagonism between Krahns, Gios and Manos. In retaliation, Johnson, himself an ethnic Gio, joined Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) and mobilised the grievances of his kinsmen in waging Liberia’s destructive civil wars, from 24 December 1989 till 2003.

Prince Johnson reinvented

Johnson’s legacy is somewhat disproportionate to his time spent in the country as the head of a warring faction. During Liberia’s 14 years of civil war, Johnson spent less than three years in the country, much less than Taylor who endured to the end.

During Operations Octopus, launched by Taylor in 1992 against the ECOMOG peacekeeping force, Johnson fled to Nigeria after narrowly escaping capture and execution by the NPFL. Early in the civil war, Johnson broke away from Taylor’s NPFL and formed his own rebel movement, called the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL), a score that Taylor tried to settle. Using more than 200 orphan children as human shields, he found refuge with West African peacekeepers and negotiated his exit out of Liberia.

In Nigeria he joined a seminary and became ordained as an evangelist. He also used his time away to write a memoir. After more than ten years in exile, Johnson returned to Liberia shortly after the Accra peace agreement was signed on 18 August 2003.

To understand Johnson’s return and his eventual rise in Liberia’s post-war politics is like a well scripted Hollywood play, one that sets out to reinvent a villain, demonstrating a life of redemption and renewed purpose. In his carefully scripted image, Johnson traded in two unique symbols, the Holy Bible and his memoir, to reinvent himself as a born-again Christian, a preacher and a man who could be entrusted with public office.

In one hand, he holds the Bible which, for his purpose, symbolised reconciliation, atonement and a new beginning. He visited Samuel Doe’s widow and other members of the family in the spirit of forgiveness and let bygone be bygone. On 9 September 1990, Johnson captured Liberia’s president Samuel Doe, and ordered that his ear be mutilated, before he was killed, a horrific scene that was captured on camera by a Palestinian television crew, who disseminated the video widely.

In the other hand, he brandished his memoir, The Rise and Fall of Samuel K. Doe: A Time to Heal and Rebuild Liberia. If the Bible was used to appeal to those prone to forgiveness, the memoir was Johnson’s instrument of ethnonationalism, his road map to use distorted memories and redeploy these memories as political weapons.

The kingmaker

Liberia’s first post-war elections was characterised by fear. By then, Liberia had had 13 peace agreements, and all had failed. The Accra Agreement was the fourteenth peace agreement. Though Charles Taylor - who was considered as the most powerful warlord - had been removed from the equation of Liberian politics, due to his indictment for war crimes in Sierra Leone, there was no guarantee that the Accra agreement would be any different from the previous ones. In certain counties, Grand Gedeh and Nimba especially, electorates felt insecure about their ethnic identities. Johnson, who had returned from exile few years earlier, ran as a senator. He capitalised on the ethnic insecurity of his kinsmen by transmitting the social memories of the 1980s and 1990s.

In the 1980s, a conflict between two coup plotters and comrades-in arms, Samuel K. Doe and Thomas Quiwonkpa, a native of Nimba county, went terribly wrong and it took on ethnic proportions. Quiwonkpa, an ethnic Gio and mentor to Johnson, launched a coup in November 1985, following the rigged election of October which sought to keep President Doe in power. The coup was foiled, and Quiwonkpa got captured and executed. Johnson, a member of the Armed Forces (AFL) of Liberia -who had joined ranks of the coup plotter- escaped to the Ivory Coast. In retaliation, Gios and Manos were hounded and persecuted for their perceived sympathy to Quiwonkpa’s failed coup.

When Liberia imploded into a civil war in 1989, this ethnic antagonism festered with retaliatory killings on both sides. During the 2005 elections’ campaign, Johnson used these memories as weapons to rally votes. “If you don’t vote for me, and we return to war, don’t count on me for support,” he said. For, if there was one person in all Nimba county with the bonafide of an ethnonationalist, it was Johnson. To his kinsmen, he had earned the right to feel entitled and ask for loyalty, for he had captured, tortured and executed on camera the one person who was perceived as an existential threat to Nimbians, Doe.

Johnson’s campaign strategy proved effective. Nimbians voted county-wide, making him a senior senator with a nine-year tenure. Next to Montserrado, Nimba county is the second most populous county in Liberia. Politicians like Ellen Johnson Sirleaf [President of the Republic from 2006 to 2018], who was initially unsure about Johnson’s influence in the county, quickly gravitated towards him and secured his endorsement for the runoff of her first election. From 2005 onward, everyone who wanted to be president had to seek Johnson’s endorsement. His strategy of being a preacher, a messenger of the Good News of Christ, while deploying social memories consolidated his political control on the county. The 2005 elections may have produced Africa’s first female president, but it also produced the kingmaker to Liberia’s post-war elections, a position the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) intentionally tried to undo.

The TRC used as a stage to relieve guilt

Three years after the elections, Liberia’s TRC held its first public hearings. It brought together key actors, including heads of warring factions, such as Johnson, so that they would give an account of their role during the civil wars, demonstrate remorse and seek forgiveness. But instead, the TRC’s platform was claimed by and used for grandstanding by warlords.

Johnson read pages from his memoir, indulged in half-truth and justified his atrocities. He also re-echoed his populist philosophy used during combat. Here, Johnson tried to communicate that he was a professional soldier whose mission was to remove a dictator and return the country to civilian rule. A point forcefully made when he lamented, “before 1985, I was an unknown soldier”. Johnson used this rhetoric to demonstrate his love for his people, that he joined the coup in defence of his people and in pursuit of justice. His public hearings were often interrupted by a cheering squad of young and old Liberians mesmerised by his power of oratory.

As the TRC realised that the public hearing was circumvented and that perpetrators used it as a theatre to reinvent themselves, it used its final report to show strength. The document was released a year later and listed Johnson as one of the most notorious perpetrators. Of the twelve warring factions, Johnson’s INPFL faction is accused of committing 2 % of the total violations. It recommends that Johnson and all those listed be investigated for war crimes.

The birth of the politics of silence

Relying on his growing popularity in Nimba, Johnson run for presidency in 2011. Though he knew he could not win, he used the third place position he obtained to demonstrate further his strength outside his native Nimba county and to ensure that he had a stronger voice on the governance and the future direction of Liberia. With Sirleaf-Johnson’s re-election and Johnson consolidated position beyond Nimba, the TRC final report was placed on trial and the “politics of silence” was born.

Johnson’s argument in favour of the politics of silence was his contention that the Accra agreement was about reconciliation and not prosecution. In his church, the Chapel of Faith Ministries, where he doubled as the founder and the spiritual leader, and on public radio, he argued that those pushing for prosecution were against peace and stability; that the pursuit of war crimes was counterproductive and went against the spirit of the Accra agreement.

He used this position to forge new political alliances and undermine the implementation of the TRC final report. In 2017, he endorsed George Weah’s presidency. When rumours circulated that Weah would establish the war crimes court if he wins a second term, he switched sides and supported Joseph Boakai in 2023.

A war crimes court without Johnson

In death, Prince Johnson has made his last, final escape. He will never answer to his role in the civil war before a court of competent jurisdiction. But in this escape also lies a new opportunity, to break free of the tunnel vision that is often imposed by the transitional justice’s normative and oversimplified framework when it comes to dealing with the past.

Liberia is currently in the process of creating an office to establish the War and Economic Crimes Court (WECC). The strategy for prosecution was constructed on the presumed culpability of Prince Johnson, even though the wars were complex, involving different actors, households, communities, neighbours, families and friends. Therefore, the death of Prince Johnson provides a fresh opportunity to look at the society more closely and design a strategy that is faithful to its complexities.

Aaron Weah (no relations to President George Weah) is a civil society activist and a transitional justice scholar with more than eighteen years’ experience. He is a co-author of “Impunity Under Attack: Evolution and Imperatives of Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission” and a doctoral candidate at the Transitional Justice Institute at Ulster University, United Kingdom. He has investigated grassroot community memorialisation of political violence perpetrated through massacres (from 1979 to 2003). He is the director of the Ducor Institute, a Liberia-based think tank.