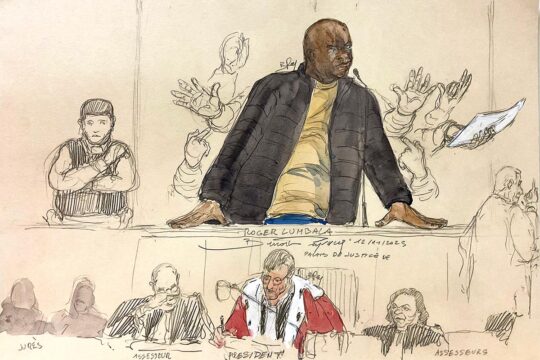

On 11 December 2024, Ian Lundin, one of the two defendants, finally spoke. This was the 164th day of proceedings, just over halfway through the biggest trial in Swedish history. At the time chairman of Lundin Oil, a Swedish oil company that changed its name several times, he is accused of complicity in war crimes committed in Sudan between 1997 and 2003. The other accused is Alexandre Schneiter, who was CEO.

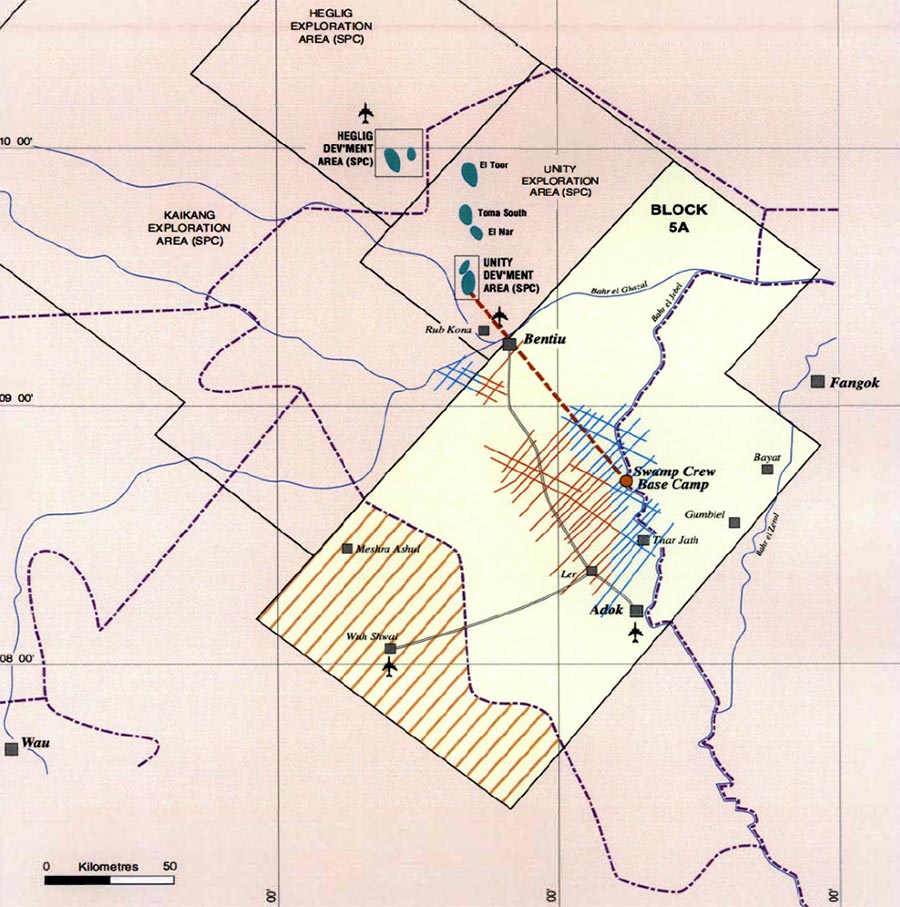

The investigation leading to this two-and-a-half year mega-trial was launched in 2010 after Magnus Elving, the prosecutor who died a year ago, read the “Unpaid Debt” report by the NGO European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS). This report examined the war crimes committed in Block 5A during the years when an oil consortium led by Lundin Oil AB was operating there. In this block covering 29,885 km2 in Unity State (now part of South Sudan), 12,000 people lost their lives and 160,000 others were displaced during the period, according to the report.

Several days are set aside for the questioning of Ian Lundin, which was interrupted for the Christmas holidays and will resume in mid-January for a few days. Alexandre Schneiter will then be questioned for a week by the prosecutors, representatives of the civil parties and by his own lawyers.

“I don’t remember”

In room 34 on the second floor of the Stockholm courthouse, a surprising exchange took place in several languages. During the four days of questioning before the Christmas break, prosecutor Karolina Wieslander put her questions to Lundin in Swedish. He is a Swedish citizen who has lived abroad all his life and speaks Swedish poorly. Although he understands the questions in Swedish, he had asked to answer in French or English, the language finally chosen. Since the start of the trial, with the exception of the civil parties from South Sudan, only Alexandre Schneiter has followed the exchanges with headphones on, as he alone does not understand Swedish. During breaks in the court’s cafeteria, the two defendants talk to each other in French.

In the witness box, Lundin told the court that the International Petroleum Corporation - the forerunner of Lundin Oil, now Orrön Energy - was an oil exploration company focused on finding and selling concessions, and that he held management positions there, insisting that he delegated technical responsibilities to his subordinates.

But Lundin’s response to questions quickly became mechanical as he repeated “I don't remember”. This seemingly frustrating answer did not deter the prosecutors who patiently weaved their web of questions to show the extent to which the company was linked to the Sudanese army.

Security management at Block 5A

Lundin was questioned about the reporting and decision-making processes within the company, particularly the security reports from Khartoum. He denies any direct involvement in operational decisions relating to security. “In a remote operation like Sudan, communication is limited and decisions have to be taken locally,” he said.

“Who made the final decision on the security protocols and military interventions around Block 5A?” asked the prosecutor. “Military decisions were not our responsibility. It was the Sudanese government that decided on the security measures around our operations,” replied the accused. A little later he said: “I think it’s normal that we were dependent on the government [in Khartoum] for security, and if the army was considered responsible for providing security that was their decision, not ours.”

“So,” continued the prosecutor, “it was apparently accepted that the army would provide security. How was this solution arrived at?”

“I don't think there was any negotiation. It came from the realisation that the local police were unable to provide security.”

“But who came up with this solution?” insisted the prosecutor.

“I don’t know, but it would be normal for the regular army to act as the main provider of security if the local police were unable to do so.”

“And who had the mandate to hold this kind of discussion?”

“The local management.”

“Who?”

“I can’t answer that exactly.”

After the break, the prosecutor resumed:

“If I have understood correctly, it was the SSDF (South Sudan Defence Forces, a militia working for the Khartoum government at the time) that was responsible for security in the area. You mentioned local police. Are we talking about the same thing?”

“I don't really see the difference between the local police and the SSDF.”

No involvement at local or operational level?

As the questions went on, Lundin explained that decisions relating to security were managed by the local team in Sudan and that his own role was limited to a strategic level, far removed from operational decisions. Ian Lundin gave the impression that he was not aware of the details of decisions taken on the ground. This is likely to increase the pressure on his co-defendant, Alexandre Schneiter of Switzerland, who had a much more operational role in the field. Some of Lundin’s answers nevertheless illustrate the complicated position in which he finds himself.

Between November 2023 and February 2024, when presenting the facts from their client’s point of view, Lundin’s lawyers repeated over and over that the conflicts in Block 5A were essentially the result of cattle rustling between clans, sometimes caused by rebels, and therefore had nothing to do with Lundin’s oil exploration activities.

During his interrogation that began last December, Lundin has remained evasive. He has not repeated his lawyers’ arguments and has avoided showing if he had a significant degree of involvement in business conduct on the ground or too detailed a knowledge of the local situation.

For example, the construction of a road was essential to access the prospecting area. However, Lundin claims that the decision to build it was taken by local teams, without his direct involvement. When the prosecution claimed that this road required military operations in sensitive areas, Lundin denied having been informed of these aspects.

Every time Lundin pleaded no memory or that he was distant from the field because of his position, the prosecution tried to bounce back.

“Didn’t you know that the militarisation of the region was designed to facilitate your operations, to the detriment of civilians?”

“My understanding was that the army was a neutral force in these factional conflicts and that it would have a stabilising effect.”

“How could the presence of the army allow you to be considered neutral?”

“That was the conclusion of the local management,” Lundin replied.

Radios supplied to Sudanese soldiers

When prosecutor Henrik Attorps took over, he showed a confidential report from the company dated June 1999, dealing with security and the need to improve communications. Citing point 9 of the report, he talked about Lundin providing equipment to soldiers, including radios for 13 men guarding the Rubkona base. Lundin took the time to read the document displayed on the wall screen in front of him, above the prosecutor. “That's not what it says,” he replied calmly after a few moments. “It says that guards are going to be equipped.”

The prosecutor moved on to another point in the document, before arriving at point 32.

“It also says that the Sudanese army will receive communication systems for the convoys, HF and VHF radios. Do you see any problem in supplying this type of equipment to an army involved in a civil war?”

“Again, it was a security force for protection purposes,” replied Lundin.

“You don’t see any problem with the fact that if you supply radios to the army, you are also helping it in general?” insisted the prosecutor, implying in its civil war operations.

“No, that’s not how I see it,” replied Lundin.

![“I think it’s normal that we were dependent on the government [in Khartoum] for security, and if the army was considered responsible for providing security that was their decision, not ours,” said Ian Lundin to the court in Stockholm last December. Ian Lundin, former chairman of the Swedish oil company Lundin Oil, speaks to the press during his trial in Sweden for alleged complicity in war crimes commited in Sudan.](https://www.justiceinfo.net/wp-content/uploads/Sweden-Sudan_Ian-Lundin-trial-speaks_@Jonathan-Nackstrand-AFP-1000x667.jpg)