“Let us start off by reiterating that there shall be no general amnesty. Any such approach, whether applied to specific categories of people or regions of the country, would fly in the face of the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] process and subtract from the principle of accountability which is vital not only in dealing with the past, but also in the creation of a new ethos within our society. (…) Government is of the firm conviction that we cannot resolve this matter by setting up yet another amnesty process, which in effect would mean suspending constitutional rights of those who were at the receiving end of gross human right violations.”

These were the words of South Africa’s president Thabo Mbeki on 15 April 2003 when he presented the sixth and final volume of the TRC, released a month earlier, to the parliament and the nation. However, within a few weeks of the speech, attempts by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to commence investigations into cases that the TRC has recommended for prosecutions were blocked. They were refused support by both the Directorate of Special Operations, a specialized unit within NPA established by Mbeki, and the South African Police Service (SAPS).

Only 849 granted amnesties

Part of the set-up of the TRC was that perpetrators of politically motivated crimes who made full disclosure were eligible for amnesty for those crimes. But perpetrators who were refused amnesty, or who chose not to apply for amnesty, were meant to face criminal prosecution. According to the TRC final report, of the 7,112 persons who applied for amnesty, some 5,034 were rejected for not meeting the basic requirements, while the others were referred to the Amnesty Committee of the TRC, that followed the completion of the truth-telling and reconciliation process (1996-98).

Some 849 of these applicants only were granted amnesty. Murders comprised the biggest category of the crimes for which amnesty was refused. The TRC handed over a list of several hundred cases to the NPA with the recommendation that they be investigated further for possible prosecution. In its report released on 21 March 2003, it asked for “a bold prosecution policy” in those cases not amnestied to avoid any suggestion that the truth and reconciliation process was a form of impunity.

Exactly the contrary happened.

The broken promise

This unsavory post-TRC history is at the heart of an application to the Constitutional Court filed on 20 January 2025, by 23 South Africans and the Foundation for Human Rights who represents survivors and families, in which they describe how the country’s political leaders have made sure that prosecutions would never take place.

“It is an undeniable fact that there have been virtually no investigations or prosecutions of the TRC cases since the TRC process concluded,” they say. And there is “substantial evidence” that the reason behind this failure is “a deliberate policy decision by the government to suppress them”.

The plaintiffs stress that for years they’ve asked for an independent commission of inquiry into the suppression of the TRC cases. “President Ramaphosa and the former Minister of Justice, Ronald Lamola, have ignored our requests,” they state. And they now want the highest court in the country to declare that the conduct of South African authorities was unlawful.

They remind that it was on the promise of such post-TRC prosecutions that “most victims accepted the necessary and harsh compromises that had to be made to cross the historic bridge from apartheid to democracy”. It is this promise, they say, that has been betrayed. “This part of South Africa’s historic pledge with victims has not been kept.” Instead, “in the aftermath of the TRC, the state chose to abandon its obligations by blocking the TRC cases.” As a result, “virtually none of these cases have been pursued”.

A political betrayal

Acquittals, opportunistic guilty pleas accompanied by suspended sentences, bungled prosecutions, constant obstruction from national security and intelligence agencies, political interference at the highest level: the dense 259-page brief filed by the plaintiffs provides the most detailed and damning account of a political betrayal that has started after Mandela’s presidency in 1999. A policy that did not apply only to crimes committed by the Apartheid regime but also by the African National Congress (ANC) or the Inkatha Freedom Party, another important anti-apartheid movement.

In early 1999, after the TRC had finalized the first five volumes of its final report, a working group called the Human Rights Investigative Unit (HRIU) was established within the NPA. It was mandated to review, investigate and prosecute TRC cases in which perpetrators had been denied amnesty or had not applied for it. The TRC then began to refer cases for potential prosecution to the NPA. The HRIU continued operations until 2000 but it didn’t proceed with any prosecutions. Another unit operated until 2003, but like the HRIU, it initiated no prosecutions.

Then came the Priority Crimes Litigation Unit (PCLU) whose mandate included to deal with the TRC cases. The PCLU launched an audit of all available cases and registered some 459 cases that were handed over from the TRC. Approximately 150 cases were identified for immediate investigation. Sixteen cases were prioritized, of which three were prepared almost immediately for indictment.

Political interference

That’s when political interference went full-scale. According to the brief, one case after another reveals the abandonment of the ambition for justice formulated in 1994 with the advent of Mandela. Like the “PEBCO 3” case, among many others:

“In 2004, former SB [Security Branch of the Police] officers Gideon Nieuwoudt, Johannes Martin van Zyl, and Johannes Koole were charged with the 1985 kidnapping and murder of three leading anti-apartheid activists, known as the PEBCO 3. This was the first and only case that the PCLU brought in respect of perpetrators who had been denied amnesty. Nieuwoudt and van Zyl applied to court to review the decisions to refuse them amnesty. The review was delayed by some five years because of the failure or refusal of the DOJ [Department of Justice] to file answering papers. Nieuwoudt died in August 2005. In 2009 the High Court ruled that an Amnesty Committee be convened to rehear the application of Van Zyl. Charges were then provisionally withdrawn against Van Zyl and Koole. Inexplicably, the DOJ never convened an Amnesty Committee and the NPA never reinstated the cases against Van Zyl and Koole, who have both since died.”

“It is highly unlikely that their decisions were spontaneous or mere coincidences,” says the brief. “It is apparent that by May 2003 both the SAPS and the NPA were reluctant to take on the TRC cases, and in all probability had been told not to do so from a political level.” The brief doesn’t shy from pointing to the highest level: “It appeared that only the head of state could make that decision, regardless of what the law and Constitution said about investigative authority.”

“The very basis of the TRC” undermined

In February 2004 an “Amnesty Task Team” (ATT) was established. According to the brief, “the ATT Report noted that a further amnesty would face challenges because of constitutional issues but nonetheless the team still had to find ways to accommodate those perpetrators who did not take part in the TRC process. Some members argued against another amnesty, pointing out it would undermine the TRC process, while others supported a new amnesty to encourage more disclosures.” And the team decided that a new amnesty similar to that of the TRC process should be offered – “to guarantee maximum impunity for apartheid-era perpetrators,” the brief argues.

The prosecution process in relation to the TRC cases now “was to be under the thumb of political overlords”. All actors were called to “take into account national interest”, which meant, say the plaintiffs, “the shielding of perpetrators of serious crimes from scrutiny and justice”.

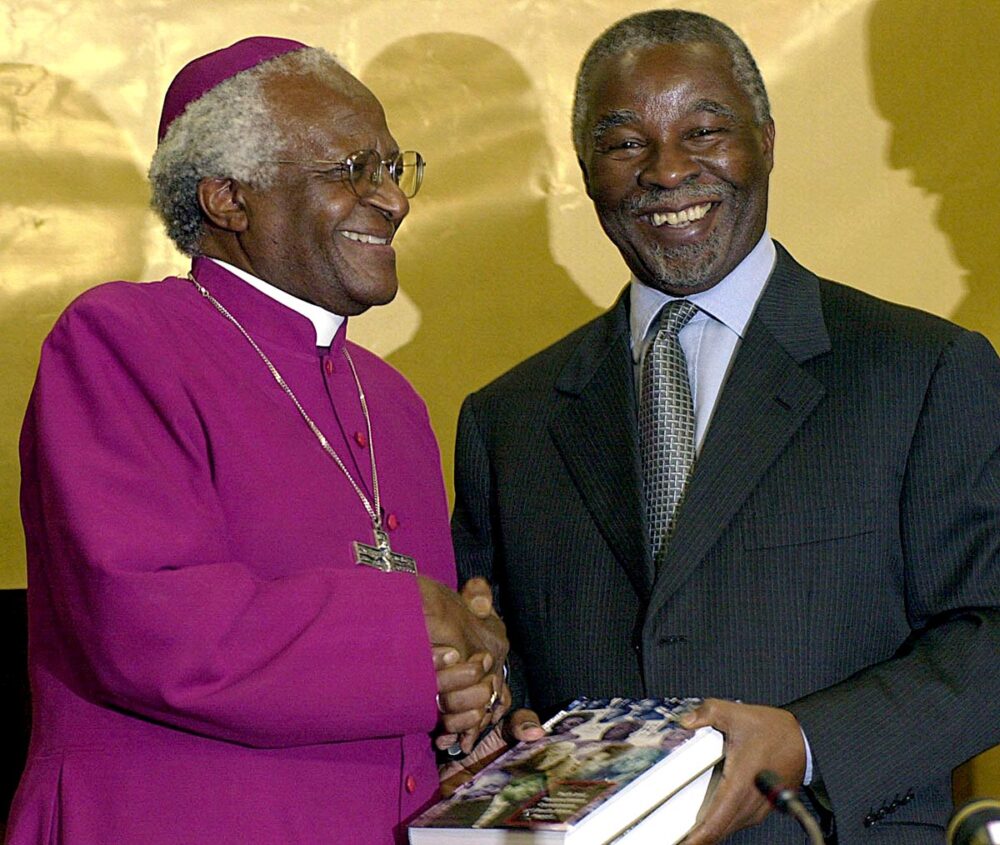

In an article published in March 2004, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the iconic chairman of the TRC, reminded that those who did not receive amnesty should face prosecution and any new initiative to stop it “would be seen as negating the amnesty process of the TRC,” the brief reports. In a further statement Tutu made in a legal case later on, he talked about “a betrayal of all those who participated in good faith in the TRC process. It completely undermined the very basis of the South African TRC.”

An order “from the very top”

It had no effect. “Between 2003 and 2004 an effective moratorium was placed on the investigation and prosecution of the TRC cases. When complainants such as Thembi Nkadimeng, sister of the late Nokuthula Simelane,” a 23-year-old member of the ANC who was abducted, tortured and forcibly disappeared by the Security Branch (SB) of the Police in 1983, “approached the PCLU they were told by prosecutors that their hands were tied as they were waiting for a new policy to deal with the so-called political cases.”

“It is not known who authorized the halting of investigations,” says the brief, “but since it involved suspending work on a large number of serious crimes, mostly involving murder, it is highly likely that the authority must have come from the very top. In addition, the heads of the NPA, DSO [the Directorate of Special Operations, a specialized unit created by President Mbeki within the NPA] and SAPS must all have acquiesced in this decision, together with the cabinet ministers overseeing those departments”.

The views of the victims and their families were not sought. “Those most impacted by this massive suspension of the rule of law were not notified in advance or given an opportunity to make representations. They were kept in the dark, and only learned of it after the fact, when they pressed the PCLU for answers.”

“In effect, hundreds of murder cases were placed on ice indefinitely on the strength of unwritten arrangements.” The moratorium remained in place for between two and three years. And when the new policy was finally issued, “the clampdown only tightened”.

The resistant prosecutors

Two key persons in the NPA, Vusi Pikoli, National Director of Public Prosecutions and Anton Ackermann, head of PCLU, did not agree with the policy. They tried to resist “the charade,” explains the brief. They chose to push the Chikane case. And that case would seal their fate.

Ackermann decided to prosecute three former SB members for their role in the 1989 poisoning of Reverend Frank Chikane, the former head of the South African Council of Churches. All the evidence implicating them had already been led in the 1997 prosecution of Colonel Wouter Basson, the former head of South Africa’s secret chemical and biological warfare programme from 1982 to 1992. Basson had been acquitted in April 2002 by the Pretoria High Court but no further investigations were deemed necessary for the three former policemen, Major-General Christoffel Smith, Colonels Gert Otto and Johannes ‘Manie’ van Staden, also involved in the case. And none had applied for amnesty for this crime.

According to Ackermann, on the morning of 11 November 2004, the police were on the verge of effecting the arrests of the three suspects. On the same morning he received a phone call from Jan Wagener, the attorney for the suspects. Wagener told Ackermann that he would receive a phone call from a senior official in the Ministry of Justice, and that he would be told that the case against his clients must be placed on hold. Shortly thereafter Ackermann did receive a phone call from an official in the Ministry of Justice. The Chikane matter should be placed on hold, he was told. According to the brief, Wagener even claimed that authorization to suspend the arrests came from President Mbeki himself, “in an extraordinarily swift move”.

No TRC case proceeded between November 2004 and August 2007.

A case against Thabo Mbeki?

Long-awaited amendments to prosecution policy came in 2006. But they “not only provided for a rerun of the TRC’s amnesty criteria behind closed doors but also opened the door to practically any excuse not to prosecute,” the brief argues. The new policy did not bring an end to the moratorium. Instead, “the clampdown continued, with renewed vigour.” No investigators were attached to the TRC cases. Ackermann’s “requests to the SAPS and the DSO for competent and experienced investigators had fallen on deaf ears,” the brief says.

Worse, it was planned by the SAPS to reappoint Senior Superintendent Karel Johannes ‘Suiker’ Britz to investigate the dockets in possession of SAPS.

Britz was a former member of the Security Branch of the Police. According to Ackermann, he had regular contacts with former Police Commissioner General van der Merwe who had formed an organization called “The Foundation for Equality before the Law”, which was intended to ensure that no further prosecutions of SB members would take place. “Britz tried to persuade me and my deputy on numerous occasions that there was a provable case of terrorism against President Mbeki arising from the landmine campaign,” wrote Ackermann. In short, if SB members were prosecuted, a secret file against Mbecki would come out.

Britz was eventually relocated to a different unit. But it was the Chikane case that would be “the tipping point which saw the complete unravelling of the attempts by the NPA to hold apartheid-era perpetrators accountable for their crimes,” the brief adds.

Former Apartheid generals still powerful

In late 2006, Pikoli, the National Director of Public Prosecutions, was summoned to a meeting which was convened at the home of the Minister of Social Development. It was attended by the Minister of Police, the Minister of Defence, and the acting Minister of Justice. “At this meeting it became clear that there was a fear that cases like the Chikane matter would open the door to prosecutions of ANC members,” said the brief. Pikoli wrote that “powerful elements within government structures were determined to impose their will on my prosecutorial decisions.”

On 5 January 2007, Justice Minister Brigitte Mabandla disclosed in a press statement the need for the development of a policy on presidential pardons for prisoners who alleged that their offences were politically motivated. Around this time, the Apartheid’s former Minister of Police, Adriaan Vlok, and the former Commissioner of Police, General Johann van der Merwe, both submitted statements to Pikoli. They both admitted to authorising the murder of Chikane and requested Pikoli not to prosecute them in the light of this disclosure.

Pikoli declined to grant them immunity from prosecution.

On 3 May 2007, Pikoli and Ackermann appeared before the Justice Portfolio Committee in Parliament. Pikoli warned that “whenever there was an attempt to charge members of the former Police Services there was political intervention, and effectively the NPA was being held to ransom by the former generals”. In his view, explains the brief, “former apartheid generals seemed to be able to exert extraordinary influence over the justice system; and were able to engineer political interventions when their people were being pursued”.

“Gloves are off”

However, despite the fact that such warning came from South Africa’s chief prosecutor, no inquiry was initiated by the Parliament.

In July 2007, after several months of negotiation between the PCLU and the attorneys of the accused in the Chikane case, a plea agreement was reached. Pikoli said he would have preferred a full prosecution because Vlok and van der Merwe had confined their disclosure to facts that were largely in the public domain and declined to reveal information about the compiling of the hit lists and who was behind their compilation. But Pikoli stated that “it was clear to me that the government, and in particular the then Minister of Justice, did not want the NPA to prosecute those implicated in the Chikane case. Therefore, a plea and sentence bargain was in my view the most appropriate compromise in the circumstances.”

On 10 July 2007, Pikoli sent a memorandum to the Minister of Justice informing her of the fact that the Chikane case would be heard in court on 17 August 2007 and that all the accused would plead guilty of attempting to murder Chikane by means of poisoning. According to Ackermann, this case ought to have opened the door to the prosecution of General Basie Smit, who succeeded van der Merwe as Commander of the Security Branch in October 1988, as well as other senior officers of both the Police forces and armed forces. That would not happen.

Shortly after the Chikane case hearing, a newspaper article appeared in which it was claimed that the NPA was preparing to prosecute ANC leaders. It was based on a forged note, says the brief, but after its publication, Pikoli was summoned to a meeting, on 23 August 2007. This meeting was attended by several cabinet ministers, including the Minister for National Intelligence Services, the Minister of Justice, and the Minister of Social Development, as well as the National Commissioner of the SAPS, Jackie Selebi. “According to Pikoli, Selebi said to him that the ‘gloves are now off’ and that he was ‘declaring war’ on him,” the brief says.

In a letter to the Minister of Justice in August 2007, Pikoli confirmed that there was no investigation by the NPA “against the 37 ANC leaders including the President of this country, contrary to the assertions of the National Commissioner of Police”. Pikoli concluded his letter by requesting an urgent meeting with the Minister. He also requested an opportunity to appear before the National Security Council “to give a true account of this issue”. The Minister did not respond.

On 23 September 2007 Pikoli was suspended from office by President Mbeki. Shortly after he learned that Ackermann had been relieved of his duties in relation to the TRC cases. “With Pikoli and Ackermann out of the way, government was in a position to appoint compliant officials to lead the NPA and take charge of the TRC cases,” says the brief. “No amount of lobbying and agitating by families and their representatives would move the new leadership of the NPA to act.”

The Chikane case was the last indictment issued in a TRC related case for some 10 years.

2017-2023: a dismal record

Things didn’t get much better ten years later.

Between 2017 and 2023 five apartheid-era inquests were reopened, four of which were at the instance and pressing of the families, notes the brief. “In all these cases, the families’ legal representatives had to threaten the NPA and/or the Minister of Justice with legal action in order to get the inquests reopened.”

Following the reopened inquest into the death of Ahmed Timol in 2017, which had been spearheaded by the Timol family and their representatives, former police officer Jao Rodrigues was charged with murder in 2018. Rodrigues died in September 2021 before he could stand trial. No one else has been charged in the case.

In May 2021 during an interview in an Al Jazeera documentary titled “My Father Died For This”, ANC legal adviser Krish Naidoo claimed that the “Cradock Four case”, one of the TRC cases, “simply fell through the cracks.”

“His statement was deeply insulting to our intelligence,” write the plaintiffs. “In fact, the TRC cases were deliberately suppressed following a plan or arrangement hatched at the highest levels of government and across multiple departments. This is the real explanation for the delay. The interference stands as a deep betrayal of those who laid down their lives for freedom in South Africa.” During that period the record of reopened cases, plea agreements and trials was “dismal,” says the brief.

South Africa’s shame

The legal brief looks at other situations in the world to shame South Africa. Chile, for instance. It is recalled that between 1998 and July 2023 Chile’s Supreme Court had handed down verdicts in more than 530 cases for dictatorship-era crimes against humanity. In Argentina, as at the end of 2021, the Office of the Prosecutor for Crimes Against Humanity had investigated 3,525 people for crimes against humanity, of whom 1,044 were convicted. “The main reason for South Africa’s woeful performance has been the political interference that effectively suppressed the pursuit of apartheid-era crimes within a few years of the closure of the TRC.”

South Africa may not be an exception though. In Tunisia today all cases transferred by the truth commission – the Instance for Truth and Dignity – for prosecution before specialized trial chambers have been systematically blocked by the government. And in The Gambia the promises for trials following another spectacular truth commission have gone nowhere for three years.

What the victims want from the Constitutional Court

The South African 23 applicants want the Constitutional Court to declare that the conduct of governments in power since 2003 in suppressing the prosecution of the TRC cases was a violation of the rights of the families and survivors to equality, human dignity and the rule of law. They want the court to say that the President’s refusal to set up a commission of inquiry into the suppression of the TRC cases is unconstitutional and violates the rights of families and survivors.

They also want the court to direct the President to establish this commission to identify the individuals responsible of the political interference over the 2003-2017 period. And they want the court to award them “constitutional damages”. The applicants do not seek individual compensation for themselves. Instead, a trust fund would be created to provide support for purposes such as commemorating their lost relatives, organising lectures or exhibitions (about 2,4 million dollars over a period of 10 years), for enabling them to assist and pursue investigations and supporting their legal cases (6,2 million dollars over 5 years), and for monitoring the work of justice authorities charged with prosecuting the TRC cases (430,000 dollars over 5 years).

Last remedy

“For most of us, it is too late. Our life-long struggle for accountability has come to naught. Suspects and witnesses have died, bringing an end to any prospect of prosecutions in most cases. These cases can never be resurrected. The cruel indifference of the post-apartheid state robbed them of justice, peace and closure. The damage done to us, our families and communities is incalculable. We are deeply scarred and will remain so until our dying day,” writes Lukhanyo Calata who is acting as the main applicant in the complaint lodged with the Constitutional Court on January 20.

“We participated in the TRC process in good faith,” writes Calata. “There was a general expectation founded on the constitutional obligations of the post-apartheid state that the state would prosecute perpetrators who were not amnestied and provide victims with reparations. For this reason, we did not sue the new South African state for the transgressions of the apartheid state. Had we known at the time the TRC was concluding its operations that the post-apartheid government had no intention of prosecuting those who had not received amnesty, most of us would have pursued civil claims against those perpetrators and the state.”

It is now left to the Constitutional Court to provide them with the last remedy they seem to have.

Lukhanyo Calata, the first of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed with South Africa's Constitutional Court on January 20, has been seeking for years to bring to justice those responsible for his father's death during the apartheid years.