On 27 January 2025, Rwandan-backed M23 soldiers seized the Congolese city of Goma. This expands Rwanda’s control in Congo, which now includes most of the province of North Kivu with the possibility of deeper incursions. Goma is home to two million people, one million of whom are internally displaced from other areas of conflict. The fighting has brought scores of deaths as well as extensive and pervasive sexual violence in what the UN and others label a devastating humanitarian catastrophe. Observers warn that we may be witnessing the beginning of another massive central African war.

Violence in Africa is often wrongly discounted as local, organic and/or inexplicable. Indeed, the causes of this particular violence seem straightforward, manufactured, and explicitly international. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is rich in rare materials necessary for the green transition. For example, it produces 80% of the world’s cobalt, essential for batteries. A 2018 report called these minerals “green conflict materials: the fuels of conflict in the transition to a low-carbon economy.” The countries poised to lead the green transition do not possess these necessary materials themselves.

The violence in North Kivu can thus be understood as part of a modern-day, state-funded gold rush. M23 is expanding its control of rare-mineral mines, and Rwanda is in the meantime benefiting from a 900 million euros mineral export treaty with the European Union (EU). The 2024 treaty with the EU exists even though Rwanda itself does not possess the materials sought. Critics therefore call the treaty a license for expropriation and violence.

International Law, between recognition and redress

Following World War II, a series of innovations in international law sought to constrain the means and methods of mass violence. Each was far-reaching and imaginative, and each could arguably address the current violence in DRC.

International humanitarian law (IHL), defined by 1949’s Geneva Conventions, set out war rules. Instead of trying to outlaw war, a losing proposition, IHL regulates how wars are fought, making certain actions, like targeting civilians, impermissible. M23’s IHL violations are well documented, as are those of Rwandan government forces.

Moreover, recent international law developments are addressing the gap between recognition and redress. In a break from practice and tradition, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Uganda to pay USD 325 million in reparations to DRC for violations of IHL committed between 1998 – 2003. Even more noteworthy, perhaps, is that Uganda has been paying! DRC cannot engage the ICJ in its claims against Rwanda, however, because Rwanda has not accepted ICJ jurisdiction.

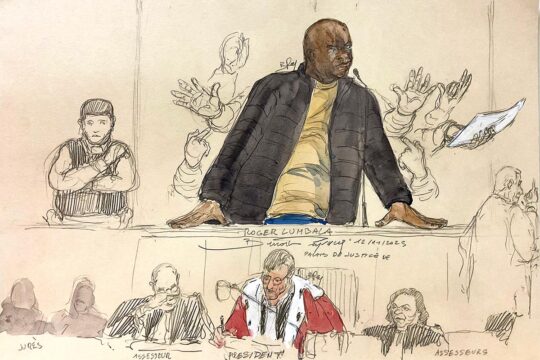

Another post World War II innovation is the development of international criminal law and international human rights law, which enable courts to look inside states and adjudicate what is happening. This innovates by challenging sovereign rule and making internal state affairs other people’s business. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has previously held an M23 commander, Bosco Ntaganda, guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, and has promised to renew its investigations of the situation in North Kivu. On the precipice of mass violence, however, the promise of future prosecution may feel late and empty to victims of the conflict.

This leaves what is arguably the most far-reaching innovation in post-war legal constructions: the UN Charter’s (1945) prohibition against the use of force. Article 2(4) holds that states must not use or threaten violence against other states, except in self-defense. This challenges a humanity-old paradigm of states as hungry entities that grow richer and more powerful through empire, redefining states’ relations to each other.

It is also the element of international law that currently holds the most potential for addressing Rwanda’s violent incursions into DRC. This is because while much international law requires adjudication before a court, Article 2(4) is enacted under international law through the principle of non-recognition. This holds that aggressive acts by states should not be legitimized by other states. This opens up political, collective methods of addressing violations of international law, such as the sanctions regime organized against Russia in response to its 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Rwanda Inside and Outside of International Law

I have written extensively on Rwanda’s problematic conduct under international law. One chapter of my latest book The Justice Laboratory: International Law in Africa examines how Rwanda used the international resources allocated to it after the 1994 genocide to support its illiberal regime. I reiterated some of these points in an essay last year detailing DRC’s unsuccessful attempts to constrain M23 using international law.

Liberal states’ continued support of Rwanda's illiberal regime is perplexing. In 2012, the EU cut aid to Rwanda in relation to atrocities committed by M23. Calls have been mounting for the EU to do the same in response to the ongoing violence. But since 2012, European countries have become more entwined with Rwanda, not less. Fast forward to 2025 and Rwanda is a trusted partner helping European states meet their mineral needs in their technology race against China as well as a housing partner promising to receive Europe-bound migrants.

Rwanda’s president for life Paul Kagame has started making statements claiming that the Kivu region is part of Rwanda. While Kagame insists M23 is not a Rwandan force, no serious observer agrees. We are therefore left with an obvious challenge to Article 2(4) and the accompanying requirement that other states call out Rwanda’s aggression and isolate it accordingly.

Renewing our vows to protect peace

There is a fair amount of discussion about how we are living the demise of the liberal international order. US territorial threats against its NATO ally Denmark about Greenland follow Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a global order paralyzed about how to address the devastation of Gaza. An EU willing to reap the benefits of DRC’s expropriated resources won through violent conquest would seem to be yet one more marker of this demise.

The principle of non-recognition is the international law that does the most to protect international peace. A norm against empire, it is morally convincing in its own terms. It is also practically available to individual states as well as institutions of the global community; we have but to renew our vows.

Kerstin Carlson is an Associate Professor at Roskilde University (Denmark), where her work focuses on the development of international law and legal institutions in the practice of transitional justice. She also teaches at The American University of Paris, where she is co-director of the Justice Lab. She is the author of The Justice Laboratory: Reconceptualizing International Law in Africa (Chatham House/Brookings Institute, 2022).