Venezuela’s spiraling repression presents a unique opportunity for the International Criminal Court (ICC) to prove it can deliver real impact on the ground. By pressing forward with its investigation into alleged crimes against humanity, the ICC Prosecutor’s Office has a chance to weaken the Maduro regime’s machinery of repression, offer long-overdue justice to victims and their families, and help pave the way for a democratic transition.

Venezuela currently has two potential cases before the ICC. “Venezuela I” stems from a 2018 state referral by Argentina, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Paraguay, and Peru, and refers to brutal repression during the 2014 and 2017 protests. Security forces engaged in arbitrary arrests, torture and other widespread abuses. In 2020, the ICC prosecutor found reasonable grounds to believe crimes against humanity — including political persecution, torture, rape, and unlawful imprisonment — had been committed. “Venezuela II,” a request by Venezuelan authorities to investigate the impact of U.S. sanctions, lacks legal merit under international criminal law.

In 2021, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan formally opened the Venezuela I investigation, and signed a memorandum of understanding with the government of Nicolás Maduro, allowing his office to provide technical assistance on justice matters. Both efforts were intended to move in parallel under the principle of “positive complementarity,” which seeks to strengthen national justice mechanisms and keep the ICC as a last resort. However, in June 2023, after Venezuelan authorities sought to halt the ICC’s probe in favor of their own proceedings, the ICC ruled the investigation should continue. It found Venezuela’s efforts insufficient, as they shielded high-ranking officials while prosecuting only low-level perpetrators and failed to address crimes driven by discrimination and sexual violence.

From positive complementarity to inaction

Many perceive that the ICC Prosecutor has prioritized positive complementarity efforts over independent investigations, slowing progress on the Venezuela I case. Victims and their families, the Venezuelan democratic opposition, the ICC’s Office of Public Counsel for the Victims (OPCV) — which on November 22 urged Khan to expedite the case — and human rights organizations have all called for concrete action. More than three years after the investigation began, they demand tangible results.

The emphasis on complementarity is even more problematic given the surge in repression following the July 28, 2024 elections, where opposition candidate Edmundo González was widely recognized as winner despite a blatantly rigged process to declare Maduro president of Venezuela. As reported by the UN Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela (FFM), the government escalated its most violent repressive tactics — systematically dismantling opposition forces, suppressing independent media, and silencing dissent through intimidation, arbitrary detentions, torture, and sexual violence. (Previous FFM reports had already found evidence of crimes against humanity and judicial complicity in these abuses.) According to the latest data from NGO Foro Penal, there were 2,062 political detainees between election day and the end of the year — a stark reminder of the stakes in Venezuela and the need for urgent action.

Venezuela remains one of the few ICC cases without arrest warrants. Of the Court’s 12 ongoing and five concluded investigations, 14 have had warrants requested by the Prosecutor. Only Venezuela, Burundi and the Philippines have not had any.

The ICC has not explained this inaction, but several factors could be at play.

Why Venezuela is different than Colombia

Historically, ICC prosecutors have pursued not just prosecutions but also the broader goal of fostering domestic accountability. While this approach has often faced criticism, it aims to expand the Court’s influence beyond the cases it directly prosecutes. The idea is that when national authorities demonstrate a willingness to investigate and prosecute crimes, the ICC’s involvement can help push domestic justice efforts forward. Striking this balance requires the ICC to give national authorities space to act while also advancing its own independent analysis — and, when necessary, launching formal investigations. A prime example of this approach was the ICC’s preliminary examination in Colombia (2004-2021), which helped drive progress within its national justice system.

Applying this approach to Venezuela is particularly challenging. Genuine accountability is impossible with the country’s current judicial system, which lacks independence. Since 2004, when then-President Hugo Chávez and his allies in the National Assembly politically took over the Supreme Court, the judiciary has functioned as an extension of the executive branch. Instead of investigating serious abuses and corruption, Venezuela’s courts have become a pillar of the regime’s repressive machinery, shielding perpetrators and punishing dissent.

Another factor behind the ICC’s inaction may be financial constraints. The Court faces chronic underfunding, creating unrealistic expectations for it to fulfill an ever-expanding mandate. As its caseload grows, State Parties have failed to provide proportional financial support. Moreover, new U.S. sanctions against the ICC, according to UN experts, could lead to financial restrictions, threatening to “undermine the ICC and its investigations”.

Against this backdrop, on December 2, 2024, Khan issued a stark warning at the Assembly of States Parties. He cautioned the Venezuelan government, judges, and prosecutors that the window for domestic justice to address crimes against humanity is “running out.”

Sticks and carrots

Khan’s statement should mark the beginning of stronger action on the Venezuela case. While restoring judicial independence is critical, and Venezuela’s judiciary needs to be overhauled, it will not happen under a dictatorship. Raising the cost of repression is essential. If key figures in the regime believe that continued abuses could lead to international prosecution — whether through the ICC or cases under universal jurisdiction, like the one currently being pursued in Argentina — they may begin to explore alternatives to holding onto power brutally. This is neither an easy nor guaranteed outcome, but without the real threat of imprisonment, it simply won’t happen.

International law is clear: perpetrators of the most serious human rights violations —including crimes against humanity — cannot be granted immunity from prosecution. This applies especially to those at the highest levels of power, though is not limited to them. While numerous individuals across the government, security forces, and judiciary played a role in state repression — particularly during the crackdowns of 2014 and 2017 and the post-election period after July 28, 2024 — the legal threshold for proving international crimes and holding individuals accountable is high. Those currently facing or at risk of criminal investigations before the ICC and other tribunals for their alleged responsibility in the most serious international crimes will not be able to receive assurances of lasting impunity. The threat of prosecution and possibility of being held accountable will haunt them permanently .

However, power in Venezuela is not monolithic. Many individuals across high, mid, and lower levels of the regime’s structure have not yet been blacklisted and still have a choice. Security forces, judicial officials, and electoral authorities, for example, may see a future for themselves in a democratic Venezuela.

International law provides for alternative measures for those implicated in human rights violations that do not amount to international crimes. Options such as amnesty, pardons, reduced sentences, or non-custodial measures could be possible, but only in exchange of substantial cooperation with the judiciary, acknowledgment of responsibility, and guarantees of non-repetition. While such agreements would need to be negotiated privately, they must also involve consultation with victims and their families. This path may be morally uncomfortable for many, but — if it is aligned with international law — it could help pave the way for accountability and a democratic transition.

This process stands a far greater chance of success if it is reinforced by threat of prosecution for additional crimes committed by Venezuela authorities — including corruption, money laundering, and drug-trafficking — where prosecutors have broader discretion to offer legal incentives in exchange for cooperation.

However, for this strategy to be viable, those violently clinging to power today must come to see that repression and outright disregard for the will of the people carry real consequences. Right now, given the shifting political reality in the region and the United States, there is no clearly coordinated international response from democratic leaders in support of Venezuela’s democracy. In this vacuum, the ICC has a crucial role to play — one that demands urgent, decisive action.

This is not about politicizing the ICC. It is about recognizing the power of the law and its ability to bring accountability where domestic justice has failed.

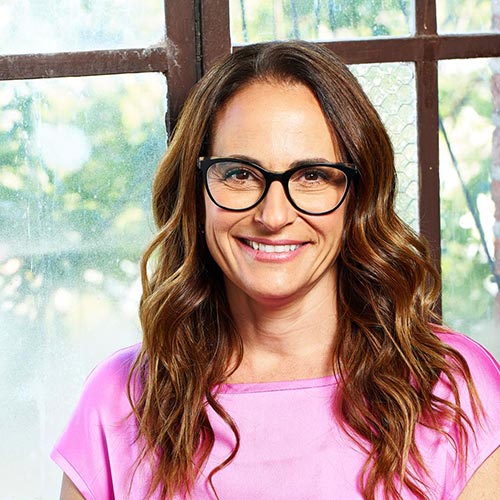

Tamara Taraciuk Broner is director of the Peter D. Bell Rule of Law Program at the Inter-American Dialogue. Before joining the Dialogue, she was the acting Americas director at Human Rights Watch. She also worked at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States. Broner was born in Venezuela and grew up in Argentina. She holds a post-graduate diploma on human rights and transitional justice from the University of Chile and a Master’s degree in Law (LLM) from Columbia Law School.