After former Yugoslavia last week, we continue our series on forgiveness with a look at the experience of South Africa and its Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1995-2002). Next week, we will wrap up with a conclusion covering all the five countries we have looked at.

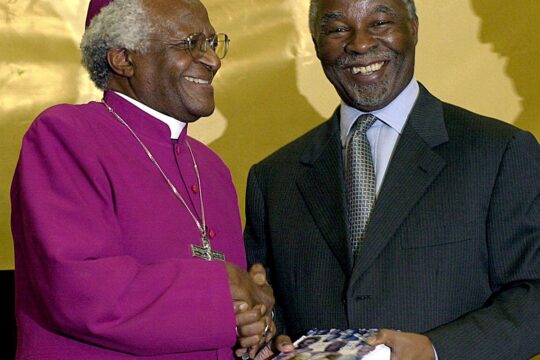

Forgiveness was at the heart of the philosophy of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. On many occasions its chairman, Desmond Tutu stressed that forgiveness was an essential condition for living together. Indeed, his main literary work is entitled “No Future without Forgiveness”. Tutu links the ethics of responsibility and the ethics of conviction, strategic forgiveness and religious forgiveness:

“We South Africans will survive and prevail only together, black and white bound together by circumstance and history as we strive to claw our way out of the abyss of apartheid racism, up and out, black and white together. Neither group on its own could make it. God had bound us together. In a way we are living out what Martin Luther King Jr. said - 'Unless we learn to live together as brothers, we will die together as fools'”.

For Desmond Tutu, the very principle of the South African TRC was based on a transaction: the unveiling of truth about the crimes in exchange for amnesty. Tutu, like the new South African president at the time Nelson Mandela, based his reasoning on the fact that imposing criminal punishment on the leaders and henchmen of the apartheid policy could lead to civil war. Hence the necessity to find a political compromise that would end years of bloody conflict and allow the black majority to acquire peacefully equal civil rights and so political power.

In exchange, the political violence perpetrated both by agents of the apartheid regime and by the ANC was amnestied. Forgiveness was thus conceived, organized and subordinated to the need for a peaceful transition, to the detriment of criminal punishment. The “truth” about the political violence, along with the merging of the hymns and flags of the ANC and the apartheid regime, was a symbolic pillar for the reconstruction of the State that Nelson Mandela wanted.

The amnesty law was contested by the widow of assassinated black leader Steve Biko and the Mixenge family, but was upheld by a decision of the Constitutional Court. In its July 15, 1996 ruling, the judge said:

“The families of those unlawfully tortured, maimed or traumatised become more empowered to discover the truth, the perpetrators become exposed to opportunities to obtain relief from the burden of a guilt or an anxiety they might be living with for many long years, the country begins the long and necessary process of healing the wounds of the past, transforming anger and grief into a mature understanding and creating the emotional and structural climate essential for the "reconciliation and reconstruction" which informs the very difficult and sometimes painful objectives of the amnesty articulated in the epilogue. (…) If the Constitution kept alive the prospect of continuous retaliation and revenge, the agreement of those threatened by its implementation might never have been forthcoming, and if it had, the bridge itself would have remained wobbly and insecure, threatened by fear from some and anger from others. It was for this reason that those who negotiated the Constitution made a deliberate choice, preferring understanding over vengeance, reparation over retaliation, ubuntu over victimisation.”

Judge Mahmood’s language here presents punishment as a process of vengeance, reprisal or victimization. However, in the same decision he also recognizes the need for justice, but puts it second to the need for reconciliation and the need for the amnesty law:

“The result, at all levels, is a difficult, sensitive, perhaps even agonising, balancing act between the need for justice to victims of past abuse and the need for reconciliation and rapid transition to a new future (…) It is an exercise of immense difficulty interacting in a vast network of political, emotional, ethical and logistical considerations. (…) The results may well often be imperfect and the pursuit of the act might inherently support the message of Kant that "out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made".

Even within the South African TRC, the Commissioners debated whether or not confessing crimes must be accompanied by repentance. Removing the risk of forgiveness being turned into a hypocritical piece of theatre, they decided that admitting to the entirety of the crimes was enough to obtain amnesty, This explains the many different positions taken by perpetrators of human rights violations, which ranged from voluntary expressions of repentance to attitudes of justifying or even condoning past crimes in the name of national security, fighting communism and subversion. An example is Major Craig Williamson, a top official in the South African security services who led a campaign of international assassinations of apartheid regime opponents, also killing university professors and a six-year-old child. He expressed neither remorse nor regret. Williamson sought to justify his actions, saying that the very nature of war is to kill. When he was granted amnesty, it caused an outcry in South Africa. The price being paid was “agonizing”, as Judge Mahmood wrote in the decision mentioned above, for part of South African society, but the country’s transition was achieved peacefully.