“I hereby initiate contempt proceedings against Robinson, issue an Order in Lieu of an Indictment against Robinson for knowingly and wilfully interfering with the administration of justice with respect to proceedings before the ICTR and/or the Mechanism,” ruled Spanish judge José Ricardo de Prada Solaesa on February 25, 2025 at the international residual mechanism that took over from the UN tribunals for Rwanda (ICTR) and former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

The decision targets American lawyer Peter Robinson for alleged violations of witness protection measures, and for allegations of false statements in files submitted to the so-called International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals.

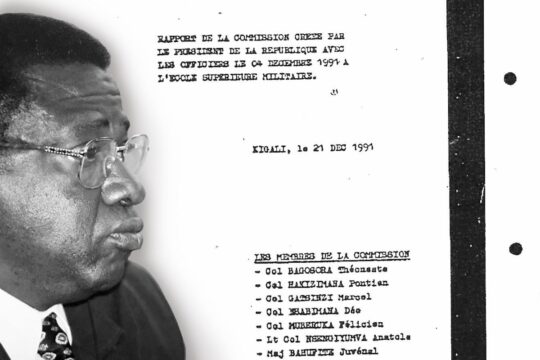

This procedure has its origins in the case of Augustin Ngirabatware, former Rwandan Planning Minister and son-in-law of Félicien Kabuga, alleged financier of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Ngirabatware was convicted of genocide by the ICTR and sentenced in December 2014 to 30 years in prison. On June 25, 2021, a Mechanism judge again convicted Ngirabatware for pressuring witnesses in his review trial. Robinson, represented Ngirabatware in these proceedings between August 15, 2015, and December 19, 2017.

During his final deliberations, the judge considered, among other things, that the case raised serious concerns regarding repeated professional and ethical misconduct by Robinson while acting as Ngirabatware’s lawyer. The Mechanism’s Registrar was then ordered to appoint an amicus curiae to investigate whether Robinson had interfered with the administration of justice and should be sanctioned. Kenneth Scott, an American expert in international criminal law and former member of the ICTY prosecutor’s office, was appointed for this purpose.

Contempt, but no harm

On April 2, 2024, after considering the observations of the amicus curiae who suggested proceedings against. Robinson, the judge decided not to proceed. The amicus appealed and, on July 17, 2024, the Appeals Chamber ruled in favour. It referred the case back to the trial court for reconsideration. The amicus curiae alleges, in particular, that. Robinson made unauthorized contact with protected prosecution witnesses, disclosed information concerning protective measures, made unauthorized contact with family members of these witnesses, and recorded interviews with protected ICTR defence witnesses without judicial authorization. The amicus curiae says that some of these witnesses wanted to retract their previous statements, in favour of Ngirabatware, as part of the review proceedings.

Scott also maintains that statements made byRobinson as Ngirabatware’s counsel are clearly false. These statements are contained in a document filed on March 2, 2016 before the Appeals Chamber, according to which he “never asked or encouraged any person to contact protected witnesses” and that he “never asked or instructed anyone to solicit any person to contact the prosecution witnesses on our behalf”. Scott adds that Robinson allegedly communicated with Ngirabatware through unauthorized personal mobile devices while he was detained at the UN Detention Facility in Arusha.

After examining the evidence produced by the amicus curiae, the judge concluded that Robinson had committed contempt of court “which at the very least, reflects a carelessness that rises to the level of reckless indifference to the consequences of his actions”. However, the judge acknowledged that “these violations were triggered primarily by Robinson’s reference to his ability to meet with protected ICTR prosecution witnesses, as authorized by the judges of the Mechanism”, that there is no evidence of any harm suffered by the protected witnesses as a result of these disclosures, and that these violations are not among the most serious allegations made by the amicus curiae. Thus, on certain allegations, the judge decided only to issue judicial warnings, reminding the American lawyer of his ethical duties.

An “unjust and unreasonable” decision

The case could have ended there, attracting the interest only of those who benefited from this poor theatre forgotten in the Tanzanian savanna costing a lot of money with no audience. But the February 25 decision caused an outcry, not only fromRobinson but also from the Association of Defense Counsel practicing before the International Courts and Tribunals (ADC-ICT) and the International Criminal Court Bar Association (ICCBA), associations of which Robinson is a member.

Robinson, who has appealed the decision – a procedure that will no doubt further advantageously feed the same actors of the Mechanism – thinks these accusations constitute a threat to the profession. “I think it is a dangerous precedent for a court to prosecute a defence counsel for a good faith interpretation of a court order,” the lawyer told Justice Info. “Defence counsel are called upon all the time to interpret court orders when representing their clients and they ought not to have to face criminal charges when the judges disagree with that interpretation.”

Robinson argues that the single judge made an error “based on an incorrect interpretation of the governing law, a patently incorrect conclusion of fact, leading to a decision that was so unfair or unreasonable as to constitute an abuse of discretion”. He notes that neither the judge nor the amicus curiae “has ever served as defence counsel in any court”. He believes that “this lack of perspective has led to a process and a decision that fails to appreciate the role and duties of defence counsel” and “fails to appreciate the dangerous precedent of imprisoning a defence counsel for his interpretation of court orders”.

According to the amicus curiae, who act as prosecutor in this case, the Appeals Chamber should dismiss his appeal as “completely unfounded and failing to demonstrate any reversible error by the Single Judge” in exercising his discretionary powers. According to the rules of procedure, the maximum penalty for contempt of court is seven years' imprisonment and a fine of 50,000 euros. In the case of a lawyer, he or she may also be prohibited from representing an accused person before the Mechanism.

The lawyers’ outcry

In a press release dated February 27, 2025, the ADC-ICT expressed its concern. “The existing confidential disciplinary procedure under the Code of Conduct, in which the ADC-ICT would have played a role, would have allowed for Mr. Robinson’s alleged conduct to have been assessed by a panel and appeals board comprised in part of his peers, before any potential criminal charges could have been brought,” it says. “Insofar as the decisions invoke the Code of Conduct,” it continues, “it is concerning that the Code’s own procedures were not followed, resulting in unequal treatment of Mr. Robinson vis-à-vis similarly situated Counsel facing allegations of the Code”.

The ICCBA says that “possible recourse to criminal proceedings should be reserved for only the most serious and egregious allegations of contempt or obstruction of justice in the context of independent counsel carrying out their mandates before the international courts”. “In all other circumstances, disciplinary proceedings should be the sole avenue of addressing actions that may amount to professional misconduct,” continues its press release dated March 3. The association says that the Mechanism’s decision “sets a highly problematic precedent and risks chilling independent counsels’ ability to act with the independence, diligence and courage required of them in the conduct of their mandates”.

The two associations, which have been granted leave to intervene as amici curiae in the Robinson case, express concern about “the inexplicable delay in bringing charges for the alleged conduct, which occurred nearly a decade ago”. “The decision to bring charges now, as the IRMCT’s operations wind down, and with no explanation for this delay, adds to our concerns as to this irregular procedure,” it states.

Tens of millions of dollars for what?

It is not yet known when and where the public hearings in this case will be held. Will it be in Arusha in the courtroom built after the ICTR closed almost ten years ago, which cost several million dollars and has never been used for real? The “inexplicable delay” denounced by the ICCBA in the Robinson case appears only the latest symptom of an institution long since abandoned to its quiet self-governance, in an attempt to justify unjustifiable costs.

The Mechanism's buildings alone cost $8.7 million. Between 2014 and 2023, the annual budget of its Arusha branch averaged around $40 million. Since then, that budget has been around 30 million per year, even if it is difficult to specify exactly within an amount – 60 million dollars in 2025 – that combines the needs of both the former ICTR and the former ICTY.

By way of comparison, the budget of the International Court of Justice in The Hague was 25 million dollars in 2020 and 32 million in 2024, the year in which that court issued 28 orders on cases such as allegations of genocide in Gaza, Myanmar and Ukraine, accusations of mass torture in Syria, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and the obligations of states around the world with regard to climate change.

Between 2020 and 2022, the Mechanism thought it could justify its existence and cost with the trial of Kabuga, who was miraculously arrested in France. Unfortunately, Kabuga turned out to be too old to be tried. And so with that loss the Mechanism officially lost its last alibi, three decades after the extermination of the Tutsis in Rwanda and the Bosniaks in Srebrenica. Since then, the Arusha officials have been trying to make the most of what they can: the transfer of a suspect from South Africa, which has been completely bogged down for two years; the precarious survival of the convicted and acquitted persons that it sent to Niger despite common sense; procedures for review that are purely formal; the monitoring of so-called “protected” ICTR witnesses, who are doubtfully in any danger or receiving real protection; and the maintenance of archives.

The problem, or the shocking nature of the situation, is not specific to this body. The UN tribunals in Cambodia and Sierra Leone also have “residual” mechanisms that continue to ensure the comfortable and quiet lifestyle of a few officials with concrete tasks that are opaque and completely derisory from a judicial point of view. This probably explains more than anything else why so much writing and hot air are devoted to the Robinson case.