The Rwandan government repeated its demand Tuesday that the archives of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) be transferred to Rwanda. This came at an official closing ceremony of the Tribunal, which is charged with trying those most responsible for the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The real end of the ICTR’s work will come on December 14, when its Appeals Chamber is due to hand down a decision in the last case. This case, known as “Butare”, involves six individuals including former minister for women and family affairs Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the only woman prosecuted by the Tribunal.

The ICTR is constructing a building at its headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania, to house its archives, which are the property of the United Nations.

Rwanda has for several years been arguing its right to house the archives on behalf of the UN. These archives include tons of video recordings of testimonies, written requests to the court and written decisions. Some of the testimonies were held behind closed doors to protect the security of witnesses.

“We will never stop asking for the archives,” said Rwandan Justice Minister Johnston Busingye. “These archives need to be hosted in Rwanda, which is a member of the United Nations.

“Time will not deter us. It is an obvious matter", he added, saying the archives belonged to his country’s history.

The Minister said Kigali would continue to seek support from Tanzania, other countries of the East African Community (EAC), the African Union and the UN Security Council for the archives to be transferred to Rwanda.

Nine suspects still at large

He also urged the international community to continue its efforts to arrest the nine-genocide-suspects-still-“at-large”-and 410 other genocide suspects sought by Rwandan judicial authorities.

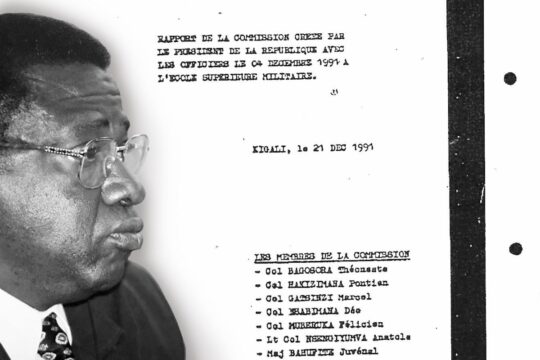

Three of the nine ICTR fugitives -- billionaire Félicien Kabuga, former Defence Minister Augustin Bizimana and former presidential guard commander Protais Mpiranya – will, if they are ever caught, be tried by the UN’s Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT) which inherits the residual functions of the ICTR.

As part of its closure strategy, the Tribunal has transferred the case files of the other six fugitives, considered “smaller fry”, to Rwanda.

Busingye said the international community’s cooperation was needed to ensure the fugitives be tried by the MICT, by national courts in the countries they are found or extradited to Rwanda.

Miguel de Serpa Soares, representing UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, stressed that “the ICTR leaves behind a powerful legacy of which we can justly be proud”.

The ICTR indicted 93 people for their suspected role in the anti-Tutsi genocide of 1994, of whom 61 have been convicted. The ICTR was set up under UN Security Council Resolution 955, which gave it a mandate to hunt down and bring to justice those most responsible for “genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda, and Rwandan citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994.”

Since the start of its first trial in 1997, the ICTR has convicted 61 people (including the six still on appeal) and acquitted 14 others. Those tried include former Prime Minister Jean Kambanda and other members of his government, army officers, businessmen, clergymen and members of the media.