“Seemingly hopeless battles are the finest ones,” lawyer Raphaël Constant told the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) one day as he was arguing a defence motion for his client Théoneste Bagosora, who was portrayed as the “mastermind” behind the Rwandan genocide. So at the end of a legal battle lasting several years, this lawyer from Martinique was relatively satisfied when Bagosora was convicted in effect only for “omissions”. Bagosora also escaped a life sentence, the maximum penalty at the UN’s ICTR which closes its doors this December.

How did Constant come to be Bagosora’s lawyer? “I was contacted by the Colonel’s son-in-law who was living at the time in Switzerland and is now in the United States,” he recounts. Constant, who is president of the Fort-de-France Bar, remembers that his decision caused him a few problems. “I received some threats,” he says. “There were also people close to me who didn’t understand, and only did so after long discussions.” He stresses, however, that his job was to “defend a man, Colonel Bagosora and not French policy in Rwanda”.

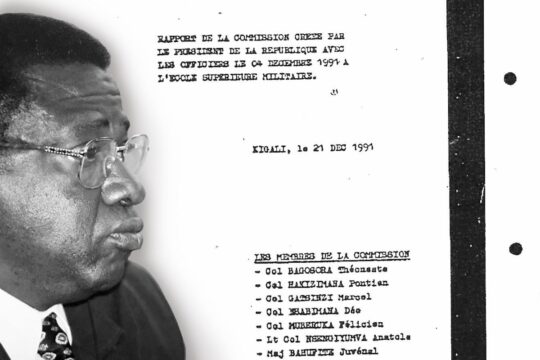

When Hutu President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down on April 6, 1994 triggering the anti-Tutsi genocide, retired officer Bagosora was Cabinet Secretary to the Defence Minister. With the minister on mission abroad, Bagosora took a certain number of initiatives. Defence Minister Augustin Bizimana returned to Rwanda three days after Habyarimana’s assassination and an interim government was set up.

Bagosora, who went into exile like other members of this government, was arrested in Cameroon on March 9, 1996 and transferred to the ICTR Detention Facility in Arusha, Tanzania on January 23, 1997.

A “Machiavellian plan”

The flagship trial in which he appeared with three other top Rwandan military officials, opened on April 2, 2002. The four men were charged with conspiracy to commit genocide, genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, crimes against humanity (including extermination and rape) and war crimes.

The prosecution alleged that from the end of 1990 to July 1994, Théoneste Bagosora and others conspired to draw up a “Machiavellian plan” to exterminate the Tutsi population and opposition members so as to keep power. This plan, according to the prosecution, included incitement to ethnic hatred and violence, training and arms distribution to militias and drawing up lists of people to be eliminated. They were alleged to have ordered and participated in massacres of Tutsi civilians and moderate Hutus. Specifically with regard to Bagosora, the prosecution alleged that after Habyarimana’s plane was shot down on April 6 he took “de facto” charge of political and military affairs in Rwanda.

The much-awaited judgment came on December 18, 2008. Bagosora and two of his co-accused were convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. They were, however, acquitted of conspiracy to commit genocide.

Constant expressed disappointment but noted nevertheless that the charge of conspiracy to commit genocide had not been retained by the Court. “What is important is that this puts into question the whole history of what happened in Rwanda,” he said.

Sentence cut from life to 35 years

The Trial Chamber accepted the Prosecutor’s arguments that Bagosora effectively commanded the Rwandan army in the three days after the April 6 attack on Habyarimana’s plane. It also found that Bagosora bore responsibility in the April 7 assassination by members of the Rwandan army of Prime Minister

Agathe Uwilingiyimana, who was perceived by extremist members of the Hutu regime to be too moderate. It also found he played a part in targeted murders of political personalities, of 10 Belgian UN peacekeepers assassinated in a Kigali military camp on April 7 and massacres of Tutsis at roadblocks in Kigali and his native region of Gisenyi, in northwest Rwanda. For such grave crimes, only a life sentence was possible.

But it was still a partial victory for the defence, according to Raphaël Constant. “No conviction for planning,” he said. “In fact, out of the 60 or so facts held against him in the indictment or by witnesses, the Tribunal only convicted him for a tiny part, concentrated over three days.” But Constant and his client did not stop there.

On May 8, 2012, the ICTR Appeals Chamber confirmed Bagosora’s conviction for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, but they overruled several of the Trial Chamber’s factual findings and reduced his sentence to 35 years. In the end he was found guilty only for having failed to prevent crimes committed by members of the military and not having punished them.

“The Appeals judges confirmed Bagosora’s guilt by default,” says Constant. “I think the myth that he was the `mastermind` behind the genocide has been debunked and that the judges retained only what they were able to.” He also believes that “acquitting Bagosora would have been impossible” because “the ICTR has never been independent of political considerations”.

Bagosora, now 74, has been imprisoned in Bamako, Mali, since July 2012, under an agreement between Mali and the UN. “I don’t have much contact with the Colonel,” says Constant. “Maybe I will go and see him when my presidency of the Bar ends in 2016.”