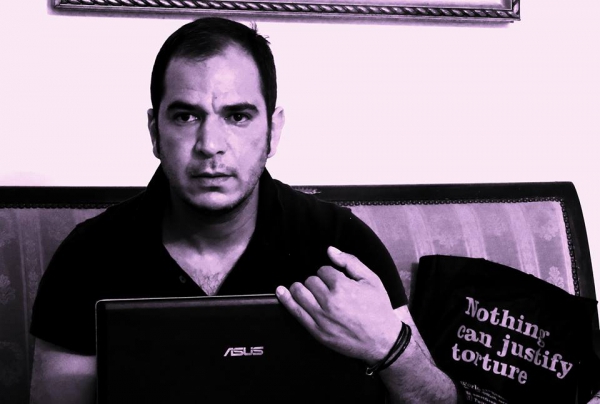

Halim Meddeb is a lawyer committed to fighting human rights violations. He also works as legal advisor at the Tunis office of the World Organization against Torture (OMCT). The OMCT, Council of Europe, UNDP and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights are all sharing expertise with the Tunisian authorities to set up an independent anti-torture mechanism in the country.

Despite a heavy legacy of torture by the old regime and ongoing human rights violations in a country threatened by terrorism, Halim Meddeb is clear: the National Torture Prevention Body is taking shape, and Parliament is expected to elect its members by the end of March.

JusticeInfo: Torture was practised as a State policy under the dictatorship. Do you think things have changed since the revolution of January 14, 2011?

Halim Meddeb: Yes, things have changed. The context is not the same. We are in a period of democratic transition and a new Constitution has been approved. Even if it is not yet being applied, it is now possible for victims to file complaints against their torturers. More than 400 complaints have been filed with the courts in the past few years. But the overall results of the last five years of transition are very mixed. There are advances in human rights, but then there are also steps backwards. Among the advances is the adoption soon after the revolution of an amnesty law for political prisoners, Tunisia becoming a member of the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture (OPCAT) and the Statute of Rome of the International Criminal Court, and signing the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Forced Disappearance. Tunisia has also made progress in other areas, such as freedom of expression and the strength of its civil society. But at times of crisis, the security argument returns as an excuse to clamp down, and we see attacks on journalists and smear campaigns against human rights defenders. After the Bardo museum attack on March 18, 2015, a repressive anti-terrorism law was passed despite opposition from civil society organizations. But we are still hopeful for the future. The day Tunisia applies the January 2014 Constitution, whose Article 23 makes torture an imprescriptible crime, rule of law will be guaranteed.

JusticeInfo: Where in Tunisia is torture still being used?

HM: In detention centres, especially when people are remanded in custody. We registered an increase after the revolution in such abuses. That’s when suspects such as Kais Berrehouma and Walid Denguir died. People who fall into the hands of the drug squad and the anti-terrorist unit generally get harsh treatment during the period of judicial investigations. The Interior Ministry says the people responsible for this violence are new recruits who were trained quickly in a short time. Ill-treatment of prisoners continues especially because Tunisia’s prisons are overcrowded. As part of an overall strategy of penal reform, we need to think of alternative punishments, rather than filling 25% of our jails with young people who have done nothing worse than smoke a joint. I don’t think there are any more instructions to torture people, but with impunity continuing and no structural reform of the security sector, old habits die hard.

JusticeInfo: Very few complaints of torture have resulted in a verdict. Is impunity still the rule here?

HM: There is in effect a lack of political will to fight impunity and tackle its causes head on. When a judge does decide to act on torture cases, he meets resistance from the judicial police, which puts up obstacles to his investigation. Out of corporatist solidarity, the security forces’ unions born after January 14 also exert a lot of pressure to remove sanctions against their colleagues, holding sit-ins in front of the courts, issuing strongly-worded statements. These things instil fear in the judges, pushing them to reverse their decisions and free security agents accused of torture. There is a terrible lack of protection for Tunisian magistrates.

JusticeInfo: Tunisian public opinion tends to favour depriving suspected terrorists of humanitarian treatment, thus seeming to justify torturing them. What do you think about that?

HM: It is true that a lot of TV stations have played along with that, allowing certain types of speech and giving airtime to people who are hardly human rights defenders. But experience shows that violence only produces more radicalization among the terrorists. This radicalization, on top of social injustice – most Tunisian terrorists come from poor, marginalized districts -- then spreads to their wives, children and people close to them.

JusticeInfo: How do you think torture should be handled in the transitional justice process, which is moving very slowly?

HM: One of the problems of transitional justice in Tunisia is the lack of consensus around the process. The Truth and Dignity Commission has lost a lot of time and met lots of obstacles in starting its work, but after nearly two years of operating it could now publish a preliminary report on torture, based on the confirmed cases handled by the Commission. And especially, it could launch a psychological support programme for victims. Since there is no vetting mechanism to guarantee non-repetition of grave human rights abuses in the security forces, the Commission could publish a list of suspected torturers, so that these civil servants of the Interior Ministry be removed from working in places of detention. A paradox in Tunisia is that a lot of torturers were promoted after the revolution!

JusticeInfo: Do you think the upcoming launch of the National Torture Prevention Body – after a lot of delays – is the answer, to end torture?

HM: The delays are not due to lack of political will because it is there, especially in parliament, which has responsibility to select candidates for this Body. Things are running late because of MP absences and the difficulty of finding certain expertise for the Body, such as retired judges and child specialists. Badereddine Abdelkafi, who heads the commission selecting candidates and was himself tortured under Ben Ali, has done a lot to get MPs to meet a few days ago to draw up a list of 48 people, that is, three candidates for each post in the new Body. Between now and the end of March, the 16 members of the Body will be chosen in a plenary session. The Torture Prevention Body will be a major tool in fighting torture. It can be a mediator and regulator in this field, but it will not be able to wipe torture out single-handedly. Also, it must not block civil society access to prisons. Tunisian jails need to be opened to the world outside, its aid organizations, schools, universities and artists!