Côte d’Ivoire has not yet delivered justice for victims of grave crimes by both sides in the country’s 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. President Alassane Ouattara and his new justice minister, Sansan Kambile, should strengthen the country’s justice system so it can deliver long overdue justice.

The 56-page report, “Justice Reestablishes Balance: Delivering Credible Accountability for Serious Abuses in Côte d’Ivoire,” outlines critical areas requiring additional government support so that Ivorian courts can provide credible justice. It is based on more than 70 interviews with government officials, members of the judiciary, representatives of nongovernmental groups, international criminal justice experts, UN officials, diplomats, and donor officials.

Victims of heinous crimes committed during the post-election crisis have suffered in silence for five long years,” said Param-Preet Singh, senior international justice counsel at Human Rights Watch. “Trials of key perpetrators from both sides would send a clear message that those responsible for grave human rights abuses cannot escape the reach of justice.”

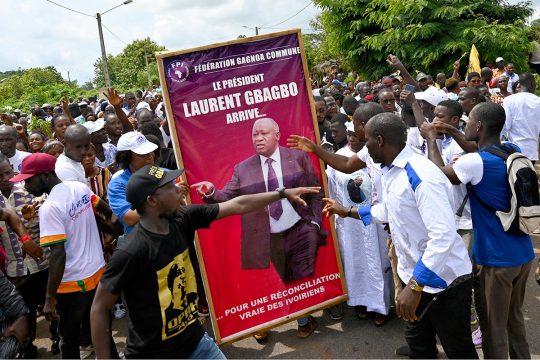

In December 2010, the failure of the incumbent president, Laurent Gbagbo, to cede power to Ouattara, the internationally-recognized winner of the presidential election, was followed by a five-month conflict during which forces loyal to both sides committed devastating abuses. They summarily executed civilians, brutally gang-raped women, and burned villages to the ground. By the end of the conflict, at least 3,000 civilians had been killed and more than 150 women raped during violence waged along political, ethnic, and religious lines.

In December 2010, the failure of the incumbent president, Laurent Gbagbo, to cede power to Ouattara, the internationally-recognized winner of the presidential election, was followed by a five-month conflict during which forces loyal to both sides committed devastating abuses. They summarily executed civilians, brutally gang-raped women, and burned villages to the ground. By the end of the conflict, at least 3,000 civilians had been killed and more than 150 women raped during violence waged along political, ethnic, and religious lines.

In June 2011, President Ouattara created a task force of judges and prosecutors – the Special Investigative and Examination Cell – to spearhead efforts to pursue those responsible for the post-election crimes. The step offered hope that the government was finally willing to address Côte d’Ivoire’s deeply entrenched culture of impunity.

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, one civil society activist warned that “the impunity of today leads to the crimes of tomorrow.” Another civil society activist said, “There was the same hatred, the same animosity, in the killing done by both sides. It will reduce tension if […] we see justice on both sides.”

After years of inadequate government support, the special cell finally received increased resources in late 2014, and in 2015, charged more than 20 people – including high-level commanders from both sides – for their role in human rights abuses during the post-election crisis. While progress in the investigations is encouraging, victims will only receive justice if perpetrators receive trials that are independent, impartial, and fair, Human Rights Watch said.

In addition to maintaining support for investigations, the government should strengthen the independence of the judiciary; protect judges, lawyers, and witnesses involved in sensitive cases; and support legal reforms that would respect the fair trial rights of defendants.

Given that many defendants have waited years for trial, Ivorian judges should release from pretrial detention any defendants who do not pose a threat to witnesses and who are not a flight risk. President Ouattara should also make clear that presidential pardons are not available for those convicted of serious abuses.

The risks associated with delivering flawed justice are very real. The trial and conviction of the former first lady, Simone Gbagbo, in March 2015, for crimes against the state – not human rights abuses – was marred by a number of fair trial concerns. The flaws in the process lent weight to efforts by Simone Gbagbo and her supporters to question the legitimacy of the proceedings and denounce the verdict.

In January 2016, the International Criminal Court (ICC) began its joint trial of Laurent Gbagbo and his close ally, Charles Blé Goudé, on four counts of crimes against humanity committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. Simone Gbagbo is also wanted by the ICC as part of the alleged “inner circle” that orchestrated mass abuses, but she remains in Ivorian custody, in violation of the government’s obligation as an ICC member to surrender her.

The ICC has yet to issue arrest warrants against anyone on the Ouattara side, although the court’s prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, said last year that her office’s investigations on the Ouattara side have intensified. The ICC has been criticized for its one-sided approach to justice in the country to date.

“The ICC’s work remains critical, to ensure victims of both sides of the conflict see justice and to enhance the court’s legitimacy in Côte d’Ivoire,” Singh said. “Credible trials in Ivorian courts, alongside the ICC’s investigations, would show the government’s willingness to work with the ICC to end impunity.”

Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners, including France, the United States, the European Union, and the United Nations, should provide financial, political, and technical assistance as needed to support the country’s effort to effectively bring accountability for the worst crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

“Côte d’Ivoire could be a model for trying serious international crimes in national trials,” Singh said. “But that potential can only be realized if Ivorian authorities mete out justice that is credible and fair.”

Article published by Human Rights Watch