The International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia’s surprise acquittal of firebrand Serb Vojislav Seselj marked the week in transitional justice, a decision that goes against previous jurisprudence of this UN court.

Judges said the prosecution had not provided sufficient evidence that Seselj was responsible for the crimes with which he was charged. "Vojislav Seselj is now a free man," declared French judge Jean-Claude Antonetti after the verdict was pronounced.

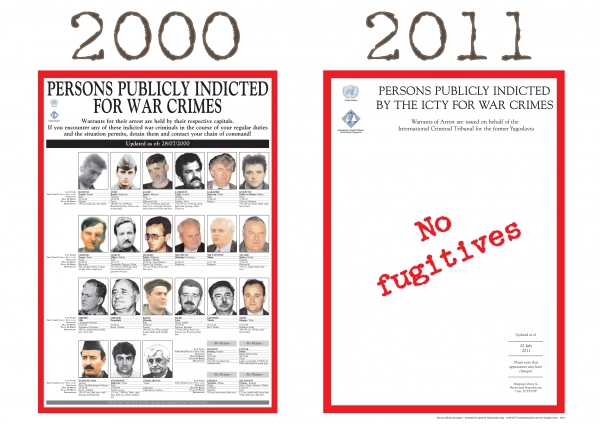

Vojislav Seselj, a former Serbian MP known for his inflammatory speeches, had been accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes over his unrelenting quest to unite "all Serbian lands" in a "Greater Serbia". According to the prosecution, he was responsible for the murders of many Croat, Muslim and other non-Serb civilians, as well as forced deportation, persecution and torture committed in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia. Although crimes were committed, a majority of the ICTY judges found that Seselj was not the "hierarchical superior" of his paramilitary forces after they came under the control of the Serbian army and was therefore not responsible for what they did. This verdict is all the more surprising given that the same tribunal had the previous week sentenced former Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic to 40 years in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity committed during the Bosnian war.

The ICTY’s decision to acquit Seselj was strongly criticized by Croatia, one of the countries where Seselj was accused of sending his militia, by victims’ organizations and several international criminal law experts. It is true that Seselj’s trial was marked by some serious procedural incidents, including witness intimidation by the Accused. The prosecution did not always show the necessary rigour in the face of this clever and tenacious man who defended himself before the Court. Seselj, who is at liberty in Serbia, is now free to run for upcoming legislative elections there, but the Prosecutor may still appeal. One of the three judges, Flavia Lattanzi, issued an unusually strong dissenting opinion, saying she felt she was thrown back to a period in human history "when there was no law in times of war”. Judge Lattanzi denounced the climate of intimidation created by the Accused and found, unlike the other two judges, that Seselj was criminally responsible since he sent his militia to Croatia, where they committed crimes against humanity. This “command responsibility” was a notable part of the recent International Criminal Court judgment against Congolese warlord Jean-Pierre Bemba.

Many countries do not have transitional justice processes, however imperfect. In Togo, ruled by the Gnassingbé family since independence, there is a semblance of a reconciliation process, but torture remains unpunished. “In Togo, acts of torture are common currency in official and secret places of detention,” writes JusticeInfo.net correspondent in Lomé Maxime Domegni, “and trying to denounce such practices is highly dangerous. Those who have the courage to raise their voices can only save themselves by going into exile, whereas the leading torturers are rewarded with promotions.

“Torture, which was used frequently during the 38-year rule of Gnassingbé Senior, remains a way of ruling for his son, now in power for 11 years. Togolese society, which had long stayed silent, started to denounce strongly this inhumane practice, especially after September 2011.”

On a more optimistic note, Tunisia continues its democratic path, despite all the obstacles. This is reflected in changes of vocabulary, as described in a book (“The new words that reflect Tunisia”) co-written by JusticeInfo.net correspondent Olfa Belhassine and Hedia Baraket. One example is the term for civil society (mojtama‘ madanî in Arabic), which has emerged as a success story of the new Tunisia, despite its limits and failures.