Colombian political scientist Ariel Avila is a specialist on the country’s guerrilla movement. He talked to JusticeInfo about the last hurdles to overcome before a peace accord can be signed to end 50 years of civil war. At the heart of peace talks taking place in Cuba is security for the rebels after they disarm. The talks could last several more months.

JusticeInfo: What is still needed for the FARC rebels and the government to sign the peace agreement?

Ariel Avila: Basically, 80% of the issues have already been dealt with. It remains to resolve the issues of disarmament, which would signal a real end to the conflict…

JusticeInfo: But that is not so simple…

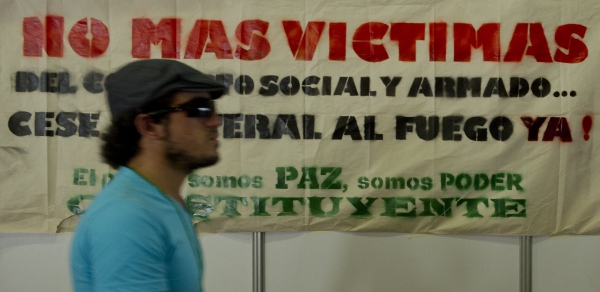

AA: There are three things that have not yet been settled. The first concerns the practical details of disarmament: where should the rebels assemble to give up their arms, in which regions, how big should these assembly zones be, what should be the rules there, etc. The second point concerns security in the countryside after disarmament. The rebels are going to disarm in rural areas where they were defending themselves. State agents will have to go into those areas to ensure security. How will they do that? What mechanisms will be set up in these regions to protect both the former rebels and the population? That’s one of the things being discussed. The last issue is whether Colombians will approve the peace deal or not. President Juan Manuel Santos wants voters to decide in a referendum and wants to set up a parliamentary peace committee [editor’s note: to draw up the necessary regulatory framework for implementation of the peace accord]. The FARC would prefer a Constituent Assembly. So in theory there is only this chapter to resolve, but it contains these three issues, currently being thrashed out in Havana.

Ariel Avila

JusticeInfo: What are the main obstacles to demobilization?

AA: There are some concerns: the economies of regions where the guerrillas are based are often dominated by illegal drug trafficking. The FARC have pledged to wipe out drug trafficking once the peace deal is signed. But bands of armed men who are already present could start killing the former guerrillas to keep control of the drugs trade. Other groups like landowners are hostile to some of the social measures decided in Havana, like land restitution. They might sabotage reintegration by funding and using these armed men against the demobilized guerrillas. The Marxist former rebels are likely to upset some people, because they have political aims, and they will defend redistribution of resources…

As well as the security challenges, the other big issue to be tackled is justice. In the regions where the guerrillas are present, they administer justice. The FARC imposes its own laws, regulates the economy and relations between the inhabitants. That will have to change. Another issue is the FARC’s participation in politics, and I think that is crucial. Finally, we need to make sure all the promises made in negotiations are actually implemented, especially in the regions that need social measures to prevent violence.

JusticeInfo.net: Why is the FARC’s return to politics a crucial issue?

AA: Because it’s at the root of our conflict! The Colombian guerrilla movement tried to do politics in the 1980s and they were massacred by State agents, together with drug traffickers and paramilitaries. That is why they took up arms. What the FARC rebels are negotiating is essentially their return to politics, and they should have their place. As I said recently in an editorial, it’s unrealistic to think the guerrilla commanders waged war for 50 years to become municipal councillors in a village. They must be allowed to enter Parliament and become presidential candidates. That’s the aim of these negotiations: to replace arms with ideas.

JusticeInfo.net: Is Colombian society ready to accept it?

AA: Even if it shocks some Colombians, there is no other way. I think urban Colombia, the people in the towns, have difficulty with it because they didn’t suffer in the conflict, don’t know much about the peace agreements and have lots of preconceived ideas on the issue. In the rural areas, there are people who support the peace process and people who oppose it. One thing is for certain: We Colombians have many wounds that need healing and many truths we need to tell each other. It will be very complex, but we need to do it to move our society forward.