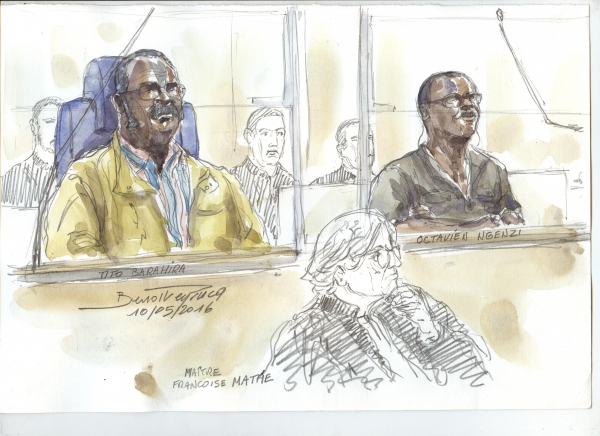

At the start of the trial, Ngenzi’s lawyer denounced the lack of means afforded to the defence, saying this was like “a battle between a tiger and a chained donkey”. But it wass not only the prosecution on the attack. Françoise Mathé, who has been defending Ngenzi since his arrest in Mayotte six years ago, plans to take France to the European Court of Justice for failure to properly respect “the exercise of the rights of the defence”. Mathé, who is co-founder of Lawyers Without Borders (ASF) France, say the investigating magistrates “did not even respond to defence requests for transport to the places concerned [in Rwanda] as part of cooperation with a country that I would call a bloody dictatorship”.

“Terrible mass crimes”

The scene has been set, and the public, although smaller than for the Simbikangwa trial two years ago, was treated to a solid, aggressive Defence act. The civil parties then responded. “For four years, investigating magistrates above all suspicion have been investigating this case in conditions that scrupulously respect the law.” Pointing a finger at the Accused, Michel Laval, lawyer for the Collective of Rwandan Civil Parties (CPCR) invoked “the terrible mass crimes that killed between 800,000 and 1 million people (…) which haunt this room”. “I have at my side an association which is not of private accusers but which is here to give a voice to all those who were hacked to death with machetes,” he continued, turning to CPCR president Alain Gauthier and his wife Dafroza.

The jury, selected from a draw the same morning, have embarked on a joyless ride for two months. The crimes of which Octavien Ngenzi and Tito Barahira are accused happened over a period of two weeks. In the region of Kabarondo, where they both held the office of mayor, the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) army arrived very soon after the genocide started, causing them both to flee. Barahira was mayor from 1976 to 1986 and says he was only an employee of the Electrogaz company when President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, killing him and sparking the genocide. “There were many problems in that area,” his interpreter translated. “and there were massacres in several places that killed especially Tutsis.”

“Problems being detained during my retirement”

“War came to Kabarondo and I had to flee with my family to Tanzania,” Barahira told the court. He went to the Benaco refugee camp with his eldest son. Then he went in search of the rest of his family to Nairobi, where his wife and other children joined him. His wife was granted asylum in France in 1998 and the children joined her. He only arrived in December 2004. “I was ill, I had high blood pressure, but I did everything I could to settle in,” said Barahira. He told the court he had a series of fixed-term contracts with cleaning companies, and his health problems continued. He obtained a disability pension which he calls his “retirement”. And then, he told the court, “I had problems being detained during my retirement”. A judicial complaint filed by the CPCR caught up with him where he was living near Toulouse. According to the prosecution, there are few testimonies detailing his actions as mayor, but “his behaviour changed sharply after 1990”. He is accused of attending “anti-Tutsi meetings” with Octavien Ngenzi and Colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita, the most powerful man in the region said to be the two mayors’ mentor. Rwagafilta, a former deputy head of the Rwandan gendarmerie who was considered an influential member of the “Akazu” (“little house”) presidential inner circle, is reportedly dead. Several witnesses say Barahira was a leader at that time. Some consider him to have been the local boss of the Interahamwe militia.

Tito Barahira appeared as a greying, sick man seated in a blue armchair. His trial will be interrupted two afternoons a week for him to get his dialysis. The investigation into his character paints him as a detached man who avoids emotional attachment and has few close contacts with his entourage. He received only three visits in prison in 2015. Only his eldest son remains close. Prosecutor Philippe Courroye’s questions appeared not to touch him. Asked about his influence (“Didn’t you have a certain prestige after 10 years as mayor?”), he anwered: “I know lots of people but they know me better than I know them”. As for his contacts with the Interahamwe he answered: “I never had any contact because there were no Interahmawe in Kabarondo.”

“Just a mayor”

Octavien Ngenzi, sitting on a bench on the left on a thick cushion, watched this exchange in a self-contained way. But when it was his turn to speak, he seemed to be struggling for words. He spoke clearly, and then softly, wrung his hands, rubbed his forearms, then told of a poor childhood, a father who was a farmer, his studies in agronomy and his appointment by the Ministry of Agriculture in his native commune of Kabarondo. “Tite”, whom he knew, was mayor. He had to visit every agricultural site in the commune which is about “162 km2”. He then resumed his studies, he said, to become an engineer.

Continuing his story, he said that “on May 6, 1986”, he met a Nissan Patrol, “the car used by the intelligence services”. A man in the back announced to him that “the President of the Republic has just signed a decree appointing you mayor”. Ngenzi said he was surprised and a bit disappointed because he had other ambitions and didn’t want to be “just a mayor”. But it was impossible to refuse. Then again he fast-forwarded his story. “I held that post from May 7, 1986 to April 16, 1994,” he said. “Then I went to Kenya, the Comoros, and Mayotte. That’s how I came here.” Ngenzi then talked about the “mixed” population of Fleury-Mérogis, and stopped short, pulling the hem of his shirt. “I am feeling overwhelmed, I am sorry,” he told the court.

“The RPF killed”

As he was being questioned, he became more confident. He opened his arms, stressing every sentence. He denied each of the accusations. “In Kabarondo there was never any racism or segregation,” he said. “We didn’t ask who is Hutu and who is Tutsi in that region.” Presiding judge Madeleine Mathieu then asked him why he did not go back to Rwanda after the war in 1995. “The RPF has been killing since 1990 and it has continued, continued,” he answered in a small voice. “I am sorry, that is the truth.” What about his activism within the presidential party, as told by witnesses, even after the advent of multiparty politics? “It wasn’t activism but what we call ‘ishaka’ in Kinyarwanda, devotion to the service of the local population,” he answered.

Like Barahira, Ngenzi described a commune apart, strangely preserved from the hatred in the rest of the country. “Up until the genocide,” he told the court. Then, he said emphatically, “it wasn’t the population that changed, it was the situation.” Ngenzi said there was no extremism but fear spreading through the population. “The extremists, we could see them from the 8 [April 1994] and whilst I was there up to the 15.” And in the rest of the country? “With regard to extremism, I can only talk about the commune of Kabarondo where I was mayor,” he answered. “I don’t know.” Prosecutor Courroye then returned to ethnic division, finding a better approach this time. “Yes, that is our problem,” cried Ngenzi. “When will it stop? It never ends. It should have ended with the genocide, which is over, but it started again on a new basis.”

Ngenzi was keyed up, but spontaneous. His lawyer seemed relieved. “Madame President,” said lawyer Mathé, “I think we have been much enlightened on the character of the Accused.” The trial continued on Friday with a hearing of Barahira’s ex-wife.